TEN INTERESTING STORIES ABOUT CONGO STAMPS

1. The Origins of Rwanda and Burundi stamps. The first stamps issued in Rwanda and Burundi, back in 1915, were from the Belgian Congo.

This complete set is from eBay on the Internet; the asking price: $1,751.45.

They were overprinted by hand stamp, “Ruanda” or “Urundi.” They took the place of German East Africa stamps as the Germans were chased out during World War I. The colony also included land ceded to Portuguese Mozambique the new British colony of Tanganyika. The early Urundi and Ruanda stamps are among the most valuable from the Congo region, since they are so rare. They quickly were supplanted by a set of machine-overprinted stamps with the confusing bilingual inscription: in French, “Est Africain Allemand — Occupation Belge,” crowded in with the Flemish, “Duitsch Oost  Africa — Belgische Bezetting.” This cluttered inscription suggests the Belgians were taking over from the Germans. But in such a case, one might ask, why still call it “German East Africa”? Was there a nationalist motive — to rub Germany’s nose in its defeat by asserting mastery over its erstwhile colony? Or was there a tacit colonial bond implied here, as though the two imperial powers were exchanging property, perhaps temporariliy, but otherwise maintaining all the imperial trappings and perquisites?

Africa — Belgische Bezetting.” This cluttered inscription suggests the Belgians were taking over from the Germans. But in such a case, one might ask, why still call it “German East Africa”? Was there a nationalist motive — to rub Germany’s nose in its defeat by asserting mastery over its erstwhile colony? Or was there a tacit colonial bond implied here, as though the two imperial powers were exchanging property, perhaps temporariliy, but otherwise maintaining all the imperial trappings and perquisites?

2. Belgian Congo stamps: A gallery of portraits. During its 83-year existence (1910-1993), the apartheid government of South Africa issued only one stamp I know of depicting a black face — a 4-cent commemorative promoting “Health Care and Service” in 1979. Though racial oppression and exclusion also was integral to the Belgian colonial administration, stamps from the Belgian Congo and Ruana-Urundi often featured black faces and bodies — even celebrated them. The early engravings are quite lovely.

3. Overprints and surcharges. Overprints and rcharges were part of Congo stamps from the beginning. In the 1880s and 1890s, three stamps from the first and second King Leopold portrait series were defaced by parcel post overprin ts. These are costly Congo stamps, because they are so rare. Later on, stamps in the colorful definitive series of 1909 were recycled numerous times. Four of them were overprinted with the year “1921”; many were surcharged with new values. Eventually, there

ts. These are costly Congo stamps, because they are so rare. Later on, stamps in the colorful definitive series of 1909 were recycled numerous times. Four of them were overprinted with the year “1921”; many were surcharged with new values. Eventually, there  were surcharges on surcharges. Imagine being confronted with a 10-centimes stamp, surcharged 30 centimes, then handstamped 25 centimes. What gives? Now go one stamp further: What about when the “0,25” is handstamped twice? Is that a double surcharge? A misprint? A new variety? So many questions! Congo postal authorities

were surcharges on surcharges. Imagine being confronted with a 10-centimes stamp, surcharged 30 centimes, then handstamped 25 centimes. What gives? Now go one stamp further: What about when the “0,25” is handstamped twice? Is that a double surcharge? A misprint? A new variety? So many questions! Congo postal authorities  kept surcharging sets through the years, up until independence and beyond, with predictably mixed results.

kept surcharging sets through the years, up until independence and beyond, with predictably mixed results.

( See Anecdote 5)

Here are examples of a double surcharge with the hand-stamped “0,25” inverted. This clearly is too much to ask a postal customer to decipher! (The image is from the Internet; eBay’s asking price for these rarities: $150.)

4. Detatchment USA? I was surprised to come across a short set of Belgian Congo stamps from the 1930s with an overprint suggesting an American occupation. I must have picked up the set at a stamp show years ago for a few bucks. The complete set (there is one more stamp) sells on eBay for as much as $100. As far as I know, the United States never occupied the Congo, or ever deployed troops there — at least openly. The Congo did play a role as an ally in World War II. The Belgian government-in-exile in London maintained its colony and provided the United States and others with key raw materials like rubber and minerals. Uranium went to the Manhattan Project that produced the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki …

To get back on the philatelic track, why a “USA Detatchment” overprint on Congo stamps from the 1930s? These stamps would not have been issued during the war, since by the 1940s there was a new definitive set in circulation. A little research turned up the following scanty information: The stamps were issued in 1931 as a “private printing.” For decades, it had not been unusual for the U.S. government to dispatch “detachments” of Marines or other soldiers to guard U.S. embassies and other assets abroad. (In Cameroon, for example.) However, there was no mention of embassies issuing postage stamps for use by the troops or anyone else. Were these stamps valid in the Congo, for example as postage on mail sent home by the U.S. troops in Leopoldville? I don’t know. I have never seen any cancelled examples of these stamps, or postally used covers including them. They may well be “Cinderellas” (a term applied to postally spurious issues, which I promise to address in a future commentary). They certainly constitute an interesting historical oddity: “American” stamps, with U.S. currency denominations and “USA Airmail” overprinted on Belgian Congo stamps. There must be more to this story.

To get back on the philatelic track, why a “USA Detatchment” overprint on Congo stamps from the 1930s? These stamps would not have been issued during the war, since by the 1940s there was a new definitive set in circulation. A little research turned up the following scanty information: The stamps were issued in 1931 as a “private printing.” For decades, it had not been unusual for the U.S. government to dispatch “detachments” of Marines or other soldiers to guard U.S. embassies and other assets abroad. (In Cameroon, for example.) However, there was no mention of embassies issuing postage stamps for use by the troops or anyone else. Were these stamps valid in the Congo, for example as postage on mail sent home by the U.S. troops in Leopoldville? I don’t know. I have never seen any cancelled examples of these stamps, or postally used covers including them. They may well be “Cinderellas” (a term applied to postally spurious issues, which I promise to address in a future commentary). They certainly constitute an interesting historical oddity: “American” stamps, with U.S. currency denominations and “USA Airmail” overprinted on Belgian Congo stamps. There must be more to this story.

By the way, during the turmoil after Congolese independence in 1960, Sweden, Ireland and Canada, among others, sent troops to the Congo at the request of the United Nations to help keep the peace. Another contingent came from India, whose postal authorities issued a set of India’s then-cur rent definitive series, overprinted “U.N. Force (India) Congo.” This set sells for a modest sum, mint or used, though cancelled copies on postally used covers mailed in the Congo might command a higher price. (Indians must have been proud of their role as international peacekeepers. Postal authorities in Delhi issued overprinted sets for use by troops in Korea in 1953; Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam in the 1950s and 1960s; and Gaza in 1965.)

rent definitive series, overprinted “U.N. Force (India) Congo.” This set sells for a modest sum, mint or used, though cancelled copies on postally used covers mailed in the Congo might command a higher price. (Indians must have been proud of their role as international peacekeepers. Postal authorities in Delhi issued overprinted sets for use by troops in Korea in 1953; Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam in the 1950s and 1960s; and Gaza in 1965.)

5. The same — and not the same. The transition from colony to independence was not easy in the Congo. Disorganization, disarray and disruption ran rampant. Economic and social upheaval was reflected in haphazard philately, including upside-down overprints known to philatelists as “inverts,” some of which sell today for $5 or $10 or more. The many surcharges created ever more opportunities for misprints and other errors. Stocks of stamps from the Belgian Congo — in particular the Flower series and the Animal series — were overprinted, some with new surcharges, and sold in Leopoldville for years after independence. As a 15-year-old stamp collector In 1964, I was able to buy stamps at the downtown Bureau de Poste to create a cover using six different versions of the original 6.50-frank stamp of the Animal series depicting two leaping antelopes.

** the original stamp, issued in 1959

** the same stamp, overprinted “CONGO” in red, issued 1960

** ditto, overprinted in black

** ditto, with a silver surcharge “5F” and red overprint, 1964

** ditto, with silver surcharge and black overprint

** finally, with a silver surcharge as well as a silver bar with black inscription “Republique du Congo” replacing “Belgisch Congo Belge.”

I have another cov er with five 20-centime stamps from the series, featuring a rhinoceros, also with varying overprints and surcharges. The last item on this cover, below right, is a most peculiar error. Let me explain:

er with five 20-centime stamps from the series, featuring a rhinoceros, also with varying overprints and surcharges. The last item on this cover, below right, is a most peculiar error. Let me explain:

While the original Belgian Congo stamp was successfully surcharged “1F” on a silver bar, the “CONGO” overprint is missing. This means the stamp looks for all the world like a new “Belgian Congo” stamp — issued in 1964, four years after independence! Another example of this phenomenon is the 15-centime value of the Flowers set, surcharged 10 centimes — but without the necessary “CONGO” overprint (see photos below) — thus inadvertently creating a new issue for the Belgian Congo after Congolese Independence Day! See below for more examples of weird surcharges.

The 60-centimes stamp from the flower set originally was surcharged “50 centimes” for the independence issue in 1960 overprinted “Congo.” But the example on the left omitted the surcharge, thus creating a new variety. The stamp on the right shows the 50-centimes surcharge, but upside-down. The middle stamp, with a 10-centimes surcharges on the original 15-centimes stamp, omitted the “Congo” overprint, thus inadvertently creating another variety for the “Belgian Congo” — after independence.

Here is an Internet image of the “new” 10-centimes stamp from the “Belgian Congo,” along with another example of the 60-centimes stamp overprinted 50 centimes — but also omitting the “Congo” overprint. How do you list stamps like these in a catalogue?

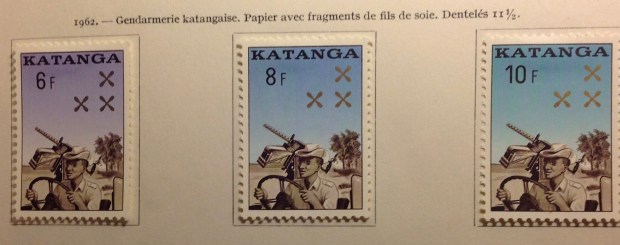

6. Impudent Katanga. The chaotic, violent years after Congolese independence included secessionist movements, some of them bloody. Moise Tshombe, from resource-rich Katanga in the southeast, led the first break from the federated government less than a fortnight after independence day June 30, 1960, proclaiming a state that lasted until January 1963. During that time Katanga issued a handful of sets, first overprints of Belgian Congo stamps, then pirated stocks of stamps from the independent Congo based in Leopoldville, and finally a few sets of original designs inscribed “Etat du/Inchi ya KATANGA.” The stamps were not recognized as valid by the International Postal Union, but mail from Katanga still got delivered. It is somewhat ja rring, to me at least, to study the first set of Katanga stamps — originally issued to celebrate the independence of the Republic of the Congo, showing a map of the whole country — with the name “Congo” obliterated by the bold overprint, “L’Etat du Katanga.” A smaller overprint cleverly covers the inscribed date of Congolese independence, “30 Juin,” with a new “11 Juillet,” Katangan Independence Day — while keeping the “1960” date uncovered. In this way, the secessionist government celebrated its own independence by repurposing stamps whose central image depicted the nation from which Katanga seceded. It is as if the U.S. Confederacy in 1861 put out a set of overprinted stamps with a map including its giant enemy to the north.

rring, to me at least, to study the first set of Katanga stamps — originally issued to celebrate the independence of the Republic of the Congo, showing a map of the whole country — with the name “Congo” obliterated by the bold overprint, “L’Etat du Katanga.” A smaller overprint cleverly covers the inscribed date of Congolese independence, “30 Juin,” with a new “11 Juillet,” Katangan Independence Day — while keeping the “1960” date uncovered. In this way, the secessionist government celebrated its own independence by repurposing stamps whose central image depicted the nation from which Katanga seceded. It is as if the U.S. Confederacy in 1861 put out a set of overprinted stamps with a map including its giant enemy to the north.

Here is the last set of stamps issued by the independent state of Katanga. The happy-go-lucky jeep driver carries what looks like an anti-aircraft gun. Many Congo-area stamps of this era, including these, were designed and produced by the Swiss company Helio Courvoisier SA.

7. Half-hearted secession. Anothe r breakaway republic was the central state of South Kasai, declared by Luba leader Albert Kalonji in August, 1960. It was a half-hearted effort — there was never a complete break wi

r breakaway republic was the central state of South Kasai, declared by Luba leader Albert Kalonji in August, 1960. It was a half-hearted effort — there was never a complete break wi th the federal government. This unlikely nation started out like its more

th the federal government. This unlikely nation started out like its more

affluent neighbor, Katanga, with overprints of Belgian Congo stamps. It then issued a few of its own design, including a souvenir sheet, before the rebellion petered out in 1962.There were a few envelopes cancelled with the

stamps from the “Etat Autonome du Sud-Kas ai.” I have one (shown here), and I hope it has some value. The stamps were not recognized by the Universal Postal Union, and while you can find them occasionally on eBay, they are not listed in most catalogues. Prices for South Kasai stamps are not high, but I believe there is some value to them because of their unusual historical provenance, their sheer oddity, and limited numbers.

ai.” I have one (shown here), and I hope it has some value. The stamps were not recognized by the Universal Postal Union, and while you can find them occasionally on eBay, they are not listed in most catalogues. Prices for South Kasai stamps are not high, but I believe there is some value to them because of their unusual historical provenance, their sheer oddity, and limited numbers.

8. Murky and murkier. The murkiest of t he sessionist “republics” were the “Republique Populaire.” declared in Stanleyville to the northwest in 1964, and the “Congo” rebellion in the northern area of Katanga, centered on

he sessionist “republics” were the “Republique Populaire.” declared in Stanleyville to the northwest in 1964, and the “Congo” rebellion in the northern area of Katanga, centered on

Notice the overprints are reversed on the cover in comparison to the set above it — a lateral invert. The cover is mine; the set is offered on eBay for $249.

Albertville, that same year. These rump rebellions, which some historians record as simba revolts aided and abetted by China, did not result in any original postage stamp designs — or much other than bloodletting. From Leopoldville, then-Prime Minister Tshombe dispatched federal troops. Some were led by mercenary officers who had fought for Tshombe in Katanga. Before they were subdued, the rebels did have time to issue overprints of Belgian Congo and Republic of Congo stamps. The cover shown below from Stanleyville offers rare “cancelled” copies of stamps from this questionable postal authority — though it is quite obvious someone merely pasted the stamps on the card and had them cancelled. This philatelic oddity did not come with a certificate of authenticity and integrity. I still cherish the cover as a rare philatelic artifact.

Postal authorities in Albertville used leftover supplies of stamps from Katanga, overprinting them simply, “Congo.” The result, in effect, was a set of stamps designed and printed by Katanga, a defunct state that had seceded from the Congo, now appropriated by a subsidiary secessionist state around Albertville and relabeled “Congo.” Is this a step forward, backward or sidewise? To com

Postal authorities in Albertville used leftover supplies of stamps from Katanga, overprinting them simply, “Congo.” The result, in effect, was a set of stamps designed and printed by Katanga, a defunct state that had seceded from the Congo, now appropriated by a subsidiary secessionist state around Albertville and relabeled “Congo.” Is this a step forward, backward or sidewise? To com pound the muddle, the rebels in Albertville managed to take the 10-centimes stamp from the 1953 Flower series, and stamp their “Congo” claim directly on top of the “Katanga” overprint that was meant to supplant the crossed-out “Belgish Congo Belge” inscription. The result is a palimpsest (a word I have been waiting for years to use, which means a series of superimposed images). The stamp pictured here is listed on eBay (price: $450). The more you look at it, the more indecipherable it becomes — an apt emblem for the state of affairs at Albertville in June of 1964, and perhaps for the Congo as a whole …

pound the muddle, the rebels in Albertville managed to take the 10-centimes stamp from the 1953 Flower series, and stamp their “Congo” claim directly on top of the “Katanga” overprint that was meant to supplant the crossed-out “Belgish Congo Belge” inscription. The result is a palimpsest (a word I have been waiting for years to use, which means a series of superimposed images). The stamp pictured here is listed on eBay (price: $450). The more you look at it, the more indecipherable it becomes — an apt emblem for the state of affairs at Albertville in June of 1964, and perhaps for the Congo as a whole …

9. A salute to colonial nostalgia. Every now and then, as my Congo collection grew, I would come across intriguing images of stamps from the handsome 1940s definitive set reprinted as mini-sheets — that is, stamps perforated and centered within a larger sheet. Some of the surrounding margins were white, others colored in alluring shades of red, green and gold. What are these sheets about? And why are they so expensive?

Eventually I consulted my  reliable Scott Standard Postage Stamp Catalogue. Here is what it said: “Miniature sheets … were printed in 1944 by the Belgian government in London and given to the Belgian political review, Message, which distributed them to its subscribers, one a month.” Scott valued each sheetlet at $12.50. The Scott catalog continued: “Remainders of these eight miniature sheets received marginal overprints in various colors in 1950, specifying a surtax of $100f per sheet and paying tribute to the Universal Postal Union. These sheets, together with the four of Ruanda-Urundi, were sold for the Committee of Cultural Works (and not at post offices) in sets of 12 for 1,217.15 francs.” Scott valued the series at “about $150. On eBay today, the series with white margins sells for $799, the series with the decorative borders is priced at $1,799.

reliable Scott Standard Postage Stamp Catalogue. Here is what it said: “Miniature sheets … were printed in 1944 by the Belgian government in London and given to the Belgian political review, Message, which distributed them to its subscribers, one a month.” Scott valued each sheetlet at $12.50. The Scott catalog continued: “Remainders of these eight miniature sheets received marginal overprints in various colors in 1950, specifying a surtax of $100f per sheet and paying tribute to the Universal Postal Union. These sheets, together with the four of Ruanda-Urundi, were sold for the Committee of Cultural Works (and not at post offices) in sets of 12 for 1,217.15 francs.” Scott valued the series at “about $150. On eBay today, the series with white margins sells for $799, the series with the decorative borders is priced at $1,799.

Does anything strike y ou about these stamp sheets? How about as an emblem imperial disassociation? An example of the oblique colonial view, disengaged, distanced, perhaps even a bit sentimental (Congo!). These sheets bespeak a European population of the 1940s, profoundly, even willfully ignorant of prevailing conditions in the Congo and the discriminatory customs and legal processes; directly or indirectly, they were complicit in those racist laws, practices and opinions. The stamps were designed and printed in London. Many Belgian Congo stamps were produced by Waterlow and Sons Ltd. In 1944, with the Belgian government-in-exile now located in the British capital, you might consider this a philatelic favor done by one imperial power for another — with a tidy profit, to be sure. Given the grim distractions of wartime, these charming little sheetlets must have been welcome surprises. They were distributed, gratis, to subscribers of Message, one accompanying each monthly issue. Look closely below, and you will see special side perforations in the sheetlets that allowed them to be stapled into the larger publication, to be safely removed later by collectors. The more elaborate, bordered sheets were sold with a 10-fold markup to honor the Universal Postal Union and benefit the Committee of Cultural Works.

ou about these stamp sheets? How about as an emblem imperial disassociation? An example of the oblique colonial view, disengaged, distanced, perhaps even a bit sentimental (Congo!). These sheets bespeak a European population of the 1940s, profoundly, even willfully ignorant of prevailing conditions in the Congo and the discriminatory customs and legal processes; directly or indirectly, they were complicit in those racist laws, practices and opinions. The stamps were designed and printed in London. Many Belgian Congo stamps were produced by Waterlow and Sons Ltd. In 1944, with the Belgian government-in-exile now located in the British capital, you might consider this a philatelic favor done by one imperial power for another — with a tidy profit, to be sure. Given the grim distractions of wartime, these charming little sheetlets must have been welcome surprises. They were distributed, gratis, to subscribers of Message, one accompanying each monthly issue. Look closely below, and you will see special side perforations in the sheetlets that allowed them to be stapled into the larger publication, to be safely removed later by collectors. The more elaborate, bordered sheets were sold with a 10-fold markup to honor the Universal Postal Union and benefit the Committee of Cultural Works.

When I get a chance, I hope to look into this further. What was Message’s view of the affairs of the Congo? Why was it chosen to distribute these stamp sheets? What was the Committee of Cultural Works, and how did it use money from the sale of these sheets? These questions beg the ultimate question: Did this philatelic enterprise in Brussels in any way enhance the well-being or even enter the consciousness of the Congolese, still living under Belgian domination, repression and exploitation in that vast, squalid African nation? I doubt many Congolese acquired these prized sheetlets. I also doubt there were many indigenous subscribers to Message in Leo, Matadi, Coquilhatville, Albertville. Not many members of the Committee of Cultural Works lived in Stanleyville, Elisabethville, Luluaburg, Thysville …

10. Paix, travail, austérité … a personal memoir. These French words mean peace, work, thrift. They are a hearty recipe for civic progress. Some combination of these ingredients promotes successful lives, communities an d societies. Yet the words have a painful poignancy, for they represent what the Congo could have become, should have become, but has fallen tragically short of becoming.

d societies. Yet the words have a painful poignancy, for they represent what the Congo could have become, should have become, but has fallen tragically short of becoming.

The words were spoken in 1962 by Cyrille Adoula (pictured below), then prime minister of the Republic of Congo. His words were transcribed as an overprint on a set of stamp s issued in October, 1962. The set originally came out in January, honoring Dag Hammerskjold, the United Nations envoy who was killed in 1961 when his plane crashed on a peace mission to the Congo. Hammerskjold had made at least four other trips to the region. In September 1961, his plane went down near Ndola, Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), close to the Congo border. Hammerskjold and 14 others were killed. One theory is that the plane was shot down on the orders of Union Miniere, the mining giant that was resisting U.N. intervention. Former president Harry Truman added to the furor when he was quoted as saying that Hammarskjold “was on the point of getting something done when they killed him.” Truman added: “Notice that I said ‘when they killed him’.”

s issued in October, 1962. The set originally came out in January, honoring Dag Hammerskjold, the United Nations envoy who was killed in 1961 when his plane crashed on a peace mission to the Congo. Hammerskjold had made at least four other trips to the region. In September 1961, his plane went down near Ndola, Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), close to the Congo border. Hammerskjold and 14 others were killed. One theory is that the plane was shot down on the orders of Union Miniere, the mining giant that was resisting U.N. intervention. Former president Harry Truman added to the furor when he was quoted as saying that Hammarskjold “was on the point of getting something done when they killed him.” Truman added: “Notice that I said ‘when they killed him’.”

Months before these stamps were issued, the doomed prime minister of the Congo, Patrice Lumumba, had been secreted to Elisabethville. Dismissed by President Kasavubu, disgraced and disheartened, Lumumba had been arrested by Col. Joseph

This portrait of Patrice Lumumba is on a stamp issued not by the Republic of the Congo, but rather the Republic of the Congo. Huh? Pardon the confusion. This stamp is from the former French Congo (why must I continue to allude to colonial days?!). Some call it Congo-Brazza, because its capital city is Brazzaville, which is located across the Stanley Basin from Leopoldville/Kinshasa along the Congo River. Lumumba was never honored on a postage stamp in his native land, that I know of. I guess Mobutu is partly to blame for that. Kasavubu, Tshombe and later, Mobuto, were featured on stamps. Tshombe’s likeness was reserved for Katanga issues, while Kasavubu stares out from a long set of Congo definitives. Later on, Mobutu’s likeness was printed on multiple sets of definitive stamps, helping to build a cult of personality and “authenticite” to mask his duplicitous and unscrupulous misrule.

Mobutu and held in Thysville, near Leopoldville. Reports say he was beaten on the plane ride to Katanga, where he was confronted by political enemies including Moise Tshombe. After more beatings and torture, Lumumba and two associates were executed by a team led by Belgian mercenaries, under orders from Katanga. Tshombe was reportedly among those present at the execution.

Cyrille Adoula suffered no such fate. Earnest but somewhat colorless, he was a trained technocrat, a banker. I wish that he had been able to lead the Congo in all sorts of promising new directions. I wish that somehow, everyone could have risen above the bloody drama of Lumumba, the proxy war of communism vs. democracy, the tribalism, the contest for Congo’s fabulous natural resources waged by the superpowers, neighboring nations and multinational corporations. With the right kind of leadership and help, the Congo could have surged forward, become a great nation. Well, why not?

A hopeful moment — Congolese Prime Minister Cyrille Adoula, right, meets JFK during a visit to Washington. Adoula was quoted on the overprinted stamps pictured above, but I don’t believe his image ever appeared on a postage stamp

In some ways, Adoula seemed the Man of the Hour. He had been an independence activist since the 1950s, when he joined with Lumumba and Ileo to form the Mouvement National Congolais (1958). He was handsome and suave. He had a modest, competent way about him. The reason I speak so extensively about Adoula is that he was prime minister during most of the time I lived in the Congo. My father, the CAO in Leopoldville, mingled with Adoula at diplomatic events and perhaps elsewhere. Pa and Mother were rather keen on Adoula’s prospects. They were Adlai Stevenson Democrats, and he was their kind of guy, with a moderate political agenda and some sensible ideas— like paix, travail, austerite. Alas, this was hardly a sensible time. Amid the turmoil before, during and after the Lumumba premiership, there were two secessionist movements — in Moise Tshombe’s Katanga, and in South Kasai. It took United Nations intervention to put the Congo back together — though seen one way you might ask: Why bother? Look who put it together in the first place: A bunch of imperialists meeting in Berlin in the 1880s, that’s who. Oh well.

By 1963, with the Congo in one piece again, Adoula tried to assemble a coalition unity government under President Kasavubu that would accommodate both the disgruntled Lumumbist elements and Tshombe’s Katangans. As if that wasn’t hard enough, 1964 brought new rebellions around Stanleyville and Albertville, and Adoula gave up, was forced out or both, yielding to none other than … Moise Tshombe. Americans, imagine the parallel: A year after the Civil War, the new head of the Re-United States is … Jefferson Davis! Adoula agreed to serve Tshombe as ambassador to the United States and Belgium. While Adoula and his family lived in Washington, Mrs. Adoula and my mother got to be a bit chummy. Pa was posted back to D.C. for a rotation, and Mother arranged with the Congolese Embassy to have a group of diaspora wives meet at our house on Madison Street. They did projects, spoke English, drank tea (sherry?), talked about babies and children and … civics, no doubt.

Mother was always terrific at this kind

Part of my Pa’s job of the Cultural Affairs Officer of he United States Information Agency in the 1950s and 1960s was to pose for dog-and-pony shows like this one. Here, in 1964, he stands at left with two apparently Congolese young men, one of whom (I’m betting the guy on the right) drew this mural of LBJ and Mt. Rushmore, which he labeled “The Shrine of Democracy,” and donated it to the U.S. ambassador. Pa decided to display it in the window of the USIS library, and had this photo snapped to honor the occasion. Turned out the artist was from neighboring Angola. …

of stuff. Both Mother and Pa found their life’s work in cultural diplomacy. Pa grew up chafing in the close confines of Boston Brahmin society. He thrived in the diverse locales where we were posted — Dhaka, Heidelberg, Leopoldville, Bremen. In the Congo, he worked hard at keeping the library going, managing cultural exchange programs, meeting and greeting and generally projecting a benign, forward-looking U.S. policy of engagement. At his side was Mother, who had “escaped” from Iowa — and from my remarkable grandmother. Janette Stevenson Murray was a civic leader, an internationalist and vocal supporter of the United Nations and Eleanor Roosevelt. She was elected to head the Cedar Rapids board of education — before women could vote in national elections. Grandma Murray was so busy with civic affairs and education that she didn’t have much attention left to pay to her five children. Her neglect apparently was not too harmful — her offspring and descendants include professors, M.D.s, Ph.d.s and M.D./Ph.D.s, world travelers and a two-time GOP candidate for governor of Iowa. When Grandma was selected American Mother of the Year in 1947, I think Mother was embarrassed by the publicity. She skipped the award ceremony at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City. To be fair, 1947 was a busy time for Mother — she was raising her young family, while Pa was transitioning from the Navy back to civilian life. Both my parents still seemed committed to moving beyond their upbringings. Besides, Mother of the Year seemed pretty square … Years later, in 1980, JMF would compile a dossier entitled, “JSM: A Reconsideration.” In it she finally — albeit a bit begrudgingly — celebrated her mother’s honor back in 1947. She acknowledged that it was quite a big deal, after all. (Editor’s note: Not any more, it seems. I don’t even know if the USA still chooses of “Mother of the Year.” Ever heard of her? How does she stack up against Miss America? Miss Universe? The Avengers?)

I was glad Mother got to make public amends with her mom — albeit seven years after Grandma died. That reconciliation affirmed her own mission, which was essentially to carry on JSM’s work — promoting international understanding, mutuality, good will and hospitality. In the 1950s

Can you spot my mother (at the right, in the back, with the pearls) among the gathering of women in Leopoldville, pre-1965? Another shot of the same party is below.

and 1960s, Grandma must have glowed over her daughter’s civic engagement work in East Pakistan, Germany, the Congo, Iceland, and Washington, D.C. Pa handled cultural diplomacy projects like the library, Fulbright scholarships and other exchanges, ran public events, sent cables to D.C., and so on. Mother organized women’s groups, and was a sparkling  hostess at lively diplomatic parties held at our house. Visiting celebrities included Marian Anderson, Jack Teagarden. John Glenn, the Dorian Quintet and Buckminster Fuller. Mother was gracious, Pa was gallant, liquor flowed. Mother would charm the men and bond with the ladies, using smarts and poise acquired at Coe

hostess at lively diplomatic parties held at our house. Visiting celebrities included Marian Anderson, Jack Teagarden. John Glenn, the Dorian Quintet and Buckminster Fuller. Mother was gracious, Pa was gallant, liquor flowed. Mother would charm the men and bond with the ladies, using smarts and poise acquired at Coe

More public diplomacy from my mom. As you can see, she really got into it.

College and Columbia Graduate School. Pa would carry on social diplomacy: schmooze, hold forth, recite poetry and share anecdotes. As a team, they were extraordinarily effective in promoting intercultural understanding and friendship. For a baker’s dozen years — from 1957 to 1970 — they did their thing around the world. I’m proud of what they accomplished. The fact that my siblings and I got to tag along was a blessing, I guess, mostly. It sure contributed to my interest in stamp collecting!

President Kasavubu: stolid schemer. Grandson of a Chinese railroad worker, Joseph Kasavubu (today spelled Kasa-Vubu) was an early advocate for independence. He also was an able politician, wily enough get himself named president of the Congo in 1960, and to hold the job until 1965, when Mobutu seized power. Afterwards, he was allowed to retire to his village, where he died in 1969. Interestingly, one of Kasavubu’s daughters also went into government. Justine Kasa-Vubu was appointed a cabinet minister in the Kabila administration in the 1990s, after Mobutu’s ouster, then to the key ambassadorship in Belgium. She broke with Kabila and ran for president in 2006.

Speaking of which: back to Congo stamps, or rather, a bit more of personal Congo history before I do. Cyrille Adoula continued to serve under Mobutu until he retired from politics in 1970. He died in 1978 at age 56 in Lausanne, Switzerland. Though I “came of age” in the Congo (age 14-16), I didn’t run in the same circles as my Ma and Pa, so I never recall meeting Adoula. I might have been introduced to him somewhere as a 15-year-old and not remember it. I know both my parents met Mobutu, though I don’t believe I ever saw him. Mother described her encounters with the future dictator, many years later, in response to my inquiry, not making a very big deal of it. “He was polite, quiet, always watching,” I think she said. No doubt some of my Congolese classmates in College Albert, the Jesuit high school I attended, were sons of the well-connected — Benares, Nsiangani, Kisangani and others. But we never socialized, maintaining a cordial, occasionally even friendly, distance.

Tshombe: the chameleon. This portrait of Moise Tshombe is superimposed on a Katangan emblem, including the trio of copper crosses. The flag of the Republic of the Congo looks startlingly similar in design, which raises the tantalizing question: Was Tshombe just kidding about his breakaway republic? In 1960 he claimed he was trying to “secede from chaos.” In 1964, he took the chance to become prime minister of that chaos. He lost popular support after he used his Belgian mercenary pals to subdue the simba rebels in Stanleyville and Albertville. In 1965, President Kasavubu sacked Tshombe, months before Mobutu sacked Kasavubu, abolished the presidency and began three decades of dictatorial rule. Tshombe returned to Spain. He died in Algeria in 1969.

I did meet Moise Tshombe, once. My recollection of that encounter is cinematically vivid: It was a summer night in Leo — August 1964, shortly after Tshombe returned from Spain to take over as prime minister of the Republic of the Congo. It was literally the eve of my departure for Europe and, eventually, the USA, where I would begin my junior year of high school at Milton Academy, a prep school near Boston. A month earlier Tshombe, the expat leader of the defunct Republic of Katanga, had been transformed into the Congo’s homecoming hero, the white knight — well, not white — summoned to unite the Congolese and make the reintegrated nation all that it could be … I was vaguely aware of all of this. I certainly knew who Tshombe was — one of the biggest stars in the Congo.

Here is Tshombe, to the right (heck, is he the only black guy in sight?) at a party that probably took place about the same time as the Fenhagens party, and could have been in Leopoldville. It certainly appears celebratory. I remember people were taking flash photos at the party. There surely was music — it was 1964, Beatles music was everywhere. But a conga line? Hey, it could have happened. Doesn’t Tshombe have a goofy expression? The man was digging it!

The scene was a crowded house party I attended with my parents at the Fenhagens. It was my 16th birthday, coincidentally. The night was warm, the air sweet. We were in a fashionable residential quarter of the capital city. Most of the guests were white, from the diplomatic community. The house had an outdoor swimming pool, a balcony, exterior lights that made the setting quite gay — like a movie set for “La Dolce Vita,” Leo-style. There were fashionable people laughing, drinking and dancing, inside and out, with some kids like me running around. In the middle of a small crowd, with the entourage that always surrounds charisma and power, there stood … Moise Tshombe. Of medium height, with a graceful build, he stood in the lights, his handsome, expressive face shining. Dressed immaculately in a tailored suit and flashy tie, smiling broadly, he worked the crowd, eyes twinkling. Clearly he was having a good time. I don’t know how he got invited to the party, but his motorcade paused on the street so he could join the fun. He had a word for everyone, spoken in elegant French of course. As he passed me, our eyes met. Ever the one with a penchant to speak up, I blurted out. “Bonsoir, M. Tshombe! C’est la premiere fois que je vous ai jamais vu!” (Good evening, Mr. Tshombe! It’s the first time I have ever seen you!”) Dumb, right? Smart politician that he was, Tshombe grasped my hand in his, grabbed my elbow with his other hand — or maybe it was just a friendly wave? — and delivered the punch line: “A la prochaine!” (Till next time!)

Here is a peek into the FMF diary! This entry is for Aug. 4, 1964 — the date of the party at the Fenhagens where I got to meet Moise Tshombe, the ex-president of Katanga, future but short-lived president of the Republic of the Congo, and alleged accomplice in the abduction and murder of Patrice Lumumba. It’s funny that my memory, no doubt reinforced by my mother, who was a bystander within hearing distance, has him saying “a la prochaine,” which is altogether more resonant and meaningful than “la prochaine fois.” The first term is a comradely salute of farewell — to the next time we meet. The second phrace literally translates as “the next time …” What does it mean? The next time we meet, I (Tshombe) will be president? I don’t think he had taken over officially at that point. He was not introduced as the president, bur rather seemed to be coming as a private citizen to the party at the Fenhagens. The second phrase — next time — if he really said it, is much more opaque, though suggestive. I wonder if I misheard it, so that my diary entry, written the same day, is less accurate than a memory reinforced by the mother … As I think about it, I grow ever more certain that I heard correctly. It was just a phrase Tshombe tossed off, a sentence fragment, a thought triggered by my reference to “la premiere fois.” Perhaps it was an unformed thought, unfinished, interrupted. Nothing to hear here. In the end, trust your eyewitness records. Accept that history is not usually resonant and meaningful, but often opaque, if suggestive … Now I’m wondering about those handshakes. How did I come to shake his hand, twice? …

(Reality check: I just thought to check my diary, which actually extends back to Pakistan in 1957, when i was nine years old. Here is my entry for Aug. 4, 1964: “Guess who I met this evening, at a party at Darby Fenhagen’s? TSHOMBE! I shook his hand 2x and told him this was the first time I had met him. He said, “La prochaine fois …” What does that mean? Anyhow, that’s quite a thing to have done on my last night in the Congo, don’t you think? Yes! That’s quite a birthday present, what?”)

Alas, there would be no “prochaine,” no next time. Napoleon’s comeback in France after his first exile was 100 days; Tshombe’s in the Congo was about a year. Like Lumumba before him, he was dismissed by President Kasavubu. Months later Col. Mobutu took over for good, then ill. He had no use for Tshombe, who retreated back to Spain. (Isn’t it interesting how these deposed heads of state managed to escape not only with their lives but with considerable means — Tshombe from copper- and mineral-rich Katanga, Albert Kalonji from diamond-rich South Kasai?)

Mobuto: the tyrant. I apologize for displaying these stamps so large, for design purposes only, because they portray such a despicable character. Col. Joseph Mobutu started making mischief even before independence, played a key role in the ouster and demise of Patrice Lumumba, and undermined the weak governments that followed. He eventually seized power, dealt with his adversaries ruthlessly, and ran the Congo like his fiefdom — a modern King Leopold — for three decades. Like the Belgian imperialist king, Mobutu deftly maneuvered with world powers. He played off the West vs. the Communists. He hijacked the venerated tradition of African “negritude,” adopting a leopard-skin cap and other accoutrements of “authenticite.” Meanwhile, he robbed his country’s wealth and ignored the welfare of his subjects. It was the 1990s before anyone figured out how to get rid of him. He “retired” to Europe, with a fortune estimated at up to $15 billion. He died shortly after his ouster, in 1997, age 66.

The Mobutu regime convicted Tshombe of treason in absentia, and he never returned to the Congo. He died in 1969 at age 58. There also would be no comeback for the Congo. In the wake of independence, secession, rebellion, bloodshed and ultimatelty, tyranny, those goals set by Cyrille Adoula — paix, travail, austerite — were trampled, gored, eviscerated. The Congo would be ruled by an ever-more-venal and corrupt system, rotten to the core of Mobutu’s megalomania and greed. He amassed and expropriated a fortune measured in billions. He ruled with casual brutality, deception, manipulation and cynical indifference toward his people for three decades. The resourceful Congolese did the best they could to cope, living in a society perpetually caught between calamity and collapse.

I can’t resist including this photo of Congolese President Mobutu Sese Soko on a state visit to Washington D.C. in 1973, meeting with Richard Nixon in the White House. Note the leopard-skin cap and the walking stick, emblems of Mobutu’s “authenticite.” He maintained a campaign of eradicating colonial influence, changing the country’s name to Zaire. It didn’t last. The capital’s name was changed early on from Leopoldville to Kinshasa, and that name stuck (Natch: No one expects the independent Congo’s capital city to remain named after its first and worst colonial master.) But the title “Zaire” turned out to be about as “authentic” as Mobutu and his fake African nationalism. After his departure, the country’s name was changed again, this time simply to: “Democratic Republic of Congo” (no more “the”).

Post-colonial nostalgia. Tshombe, right, with U.N. Envoy Dag Hammarskjold. Tshombe was president of the breakaway Republic of Katanga at the time. Hammerskjold was trying to broker a settlement and prevent a civil war. Hammarskjold was killed in September 1961 when his plane went down near the Congo border. Tshombe’s Katanga lasted into 1963, when federal forces prevailed with the help of the United Nations, the CIA, deployments from Sweden, Canada, Ireland, India, Belgian agents, mining interests, communists, Lumumbists and, and … aren’t those enough behind-the-scenes actors? (On his side, Tshombe deployed officers and soldiers-for-hire from Belgium, Italy and South Africa, with considerable success; much blood was shed; hundreds were killed in the fighting, including civilians.) In 1963 Tshombe abruptly relocated to Spain, only to return in the summer of 1964 to become president of the Republic of the Congo. That lasted a year before Tshombe was dismissed by President Kasavubu. After that Col. Mobutu took over and the democracy game was up.

Moise Tshombe was one of Africa’s most promising yet enigmatic figures. Having met him I can attest to his charisma. He was charming, urbane, smart — and apparently, ruthless. How could the man dancing in that conga line in 1964 have stood by and watched as Patrice Lumumba was tortured and executed in 1961? This portrait brings out a brooding side of Tshombe. There’s a bit of Clark Gable there, a little James Cagney, some Ernest Borgnine … Enough! Enough about Tshombe and the conga line. (Oh wait — I think they were doing a line dance called the Madison in that photo; it was all the rage in Leo in 1964 …) Now let’s get back to stamps, shall we?

ental stone facades, towers and ruins — the latter untouched since the ravages of the Franco-Palatine wars and lightning strikes hundreds of years earlier. My twin sister Anne and I, just turned 14, were completely bilingual by this time. (Indeed, I recently had ranked second in my class — in German!) I must have been indistinguishable from the locals with my blond hair, accentless German and shiny black Lederhosen. Every morning we would head off by bicycle or Strassenbahn to the Englische Institut, a German-language school where we had advanced through the classes, from Quinta or Quarta, Unterterzia and Oberterzia to Untersekunda, the rough equivalent of eighth grade. After school we would make the return trip, mount the hill past Heidelberg University and climb the 76 steps to home. When we first arrived, I was disappointed not to be attending the American school attached to the massive U.S. military installations in Heidelberg, and missing out on life in the suburban precincts of Mark Twin Village and, a little further out of town, Patrick Henry Village. By this time, however, I was pretty well assimilated. I enjoyed friendships with German and American kids, played Little League baseball, went to the PX for American movies. I was pretty comfortable in two worlds.

ental stone facades, towers and ruins — the latter untouched since the ravages of the Franco-Palatine wars and lightning strikes hundreds of years earlier. My twin sister Anne and I, just turned 14, were completely bilingual by this time. (Indeed, I recently had ranked second in my class — in German!) I must have been indistinguishable from the locals with my blond hair, accentless German and shiny black Lederhosen. Every morning we would head off by bicycle or Strassenbahn to the Englische Institut, a German-language school where we had advanced through the classes, from Quinta or Quarta, Unterterzia and Oberterzia to Untersekunda, the rough equivalent of eighth grade. After school we would make the return trip, mount the hill past Heidelberg University and climb the 76 steps to home. When we first arrived, I was disappointed not to be attending the American school attached to the massive U.S. military installations in Heidelberg, and missing out on life in the suburban precincts of Mark Twin Village and, a little further out of town, Patrick Henry Village. By this time, however, I was pretty well assimilated. I enjoyed friendships with German and American kids, played Little League baseball, went to the PX for American movies. I was pretty comfortable in two worlds.

collector-friend Jurgen lived in Leimen, a nearby village. He picked up my practice of improvising these first days covers, and kept sending me samples for more than a year after I left town. Now that’s philatelic friendship!)

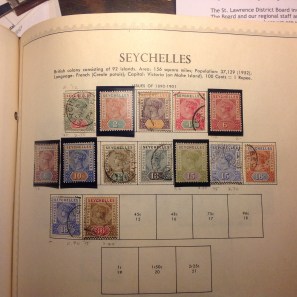

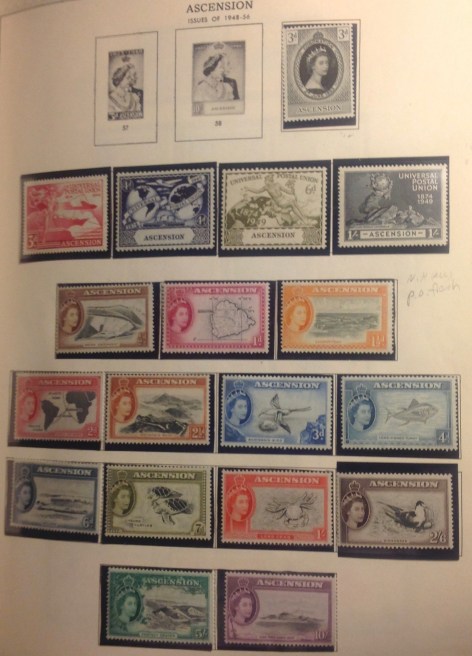

collector-friend Jurgen lived in Leimen, a nearby village. He picked up my practice of improvising these first days covers, and kept sending me samples for more than a year after I left town. Now that’s philatelic friendship!) ction of stamps, purchased at face value, which obliging postal authorities would send back to me, sometimes in envelopes embellished with a variety of current issues. Some of these stamps have increased nicely in value. (One example: the 1953 Queen Elizabeth II definitive set from Ascension, which cost me less than $5, now has a catalog value of $150+.)

ction of stamps, purchased at face value, which obliging postal authorities would send back to me, sometimes in envelopes embellished with a variety of current issues. Some of these stamps have increased nicely in value. (One example: the 1953 Queen Elizabeth II definitive set from Ascension, which cost me less than $5, now has a catalog value of $150+.)

the Belgian Congo in the middle years — 1920s to 1950s. The “mask” set of 1948 was striking, and quite common, so a few of them may have found their way into my collection. I certainly didn’t consider the Congo a specialty, like British Colonies. As it turned out, early Congo stamps were quite advanced. The 1894 multicolor definitives from the Congo Free State were exquisite engravings of local scenes, printed in black within exotic ornamental borders in different colors. Some stamps in this early set are quite affordable, and subsequent sets that used the same designs are cheap and easily available, both cancelled and mint. (It’s remarkable to think there was so much letter traffic from the Congo so long ago …) Other early Congo stamps, and others later on, are valuable. Little did I know that when I traveled to the Congo in the fall of 1962, I would be launching a philatelic expedition that now, a half-century later, has produced a nearly complete collection of stamps from the Congo. That means starting with Belgian King Leopold’s Congo Free state in 1889, then the Belgian Congo beginning in 1908, continuing past Independence Day June 30, 1960. (Indeed, as I write this, I am awaiting impatiently delivery of a key stamp filling one of my few gaps — the 50f stamp of the flower series of 1953, which I found at the Stamps to Go online store for $7.50) I am certain this collection is very valuable — worth thousands, I expect. The first set alone

the Belgian Congo in the middle years — 1920s to 1950s. The “mask” set of 1948 was striking, and quite common, so a few of them may have found their way into my collection. I certainly didn’t consider the Congo a specialty, like British Colonies. As it turned out, early Congo stamps were quite advanced. The 1894 multicolor definitives from the Congo Free State were exquisite engravings of local scenes, printed in black within exotic ornamental borders in different colors. Some stamps in this early set are quite affordable, and subsequent sets that used the same designs are cheap and easily available, both cancelled and mint. (It’s remarkable to think there was so much letter traffic from the Congo so long ago …) Other early Congo stamps, and others later on, are valuable. Little did I know that when I traveled to the Congo in the fall of 1962, I would be launching a philatelic expedition that now, a half-century later, has produced a nearly complete collection of stamps from the Congo. That means starting with Belgian King Leopold’s Congo Free state in 1889, then the Belgian Congo beginning in 1908, continuing past Independence Day June 30, 1960. (Indeed, as I write this, I am awaiting impatiently delivery of a key stamp filling one of my few gaps — the 50f stamp of the flower series of 1953, which I found at the Stamps to Go online store for $7.50) I am certain this collection is very valuable — worth thousands, I expect. The first set alone  (pictured here) is worth hundreds. (I have it complete.) I am missing a few stamps here and there — like the first parcel post stamp in 1887 (catalog value: $400+; note empty space on page). However, less than a handful are missing of the more than 400 stamps issued by the colonial administration. This collection is indeed superb, and I can’t wait to tell you more about it. First, however, a word or more of historical context.

(pictured here) is worth hundreds. (I have it complete.) I am missing a few stamps here and there — like the first parcel post stamp in 1887 (catalog value: $400+; note empty space on page). However, less than a handful are missing of the more than 400 stamps issued by the colonial administration. This collection is indeed superb, and I can’t wait to tell you more about it. First, however, a word or more of historical context. lic challenge. Since Belgium itself was bilingual — French and Flemish — the same duality would have to be reflected somehow on the stamps of its new overseas territory. French was the only language used on stamps from Leopold’s suzerainty. Now all stamps from the colony had to accommodate both languages of its new colonial masters. This awkward design requirement has been shared by other bilingual stamp-issuing nati

lic challenge. Since Belgium itself was bilingual — French and Flemish — the same duality would have to be reflected somehow on the stamps of its new overseas territory. French was the only language used on stamps from Leopold’s suzerainty. Now all stamps from the colony had to accommodate both languages of its new colonial masters. This awkward design requirement has been shared by other bilingual stamp-issuing nati Flamands! A year later, in 1909, the colony got the first set of its own — a four-stamp group that incorporated the earlier designs with the French only inscriptions. Flemish Brussels must have been in a tizzy. (Gott in Himmel! Will these pesky Walloons never show us proper respect? Congo is every bit as much ours as theirs!) Finally, in 1910, the first bilingual stamps began trickling out. The clever designers used the same engraved scenes from the 1890s — of the port city of Matadi, the Congo river at Stanley Falls, a river

Flamands! A year later, in 1909, the colony got the first set of its own — a four-stamp group that incorporated the earlier designs with the French only inscriptions. Flemish Brussels must have been in a tizzy. (Gott in Himmel! Will these pesky Walloons never show us proper respect? Congo is every bit as much ours as theirs!) Finally, in 1910, the first bilingual stamps began trickling out. The clever designers used the same engraved scenes from the 1890s — of the port city of Matadi, the Congo river at Stanley Falls, a river  steamer, hunting elephants and others. Most remarkable is a rendering of a smoke-belching engine towing cars across the M’pozo River on an elevated bridge. Remember, this design dates to the 1890s. Building the Matadi-Leopoldville railroad through the Congo was a mammoth undertaking that displayed Leopold’s relentlessness. While his stamp designers celebrated this engineering triumph, little was said about the terrible toll of this arduous railway construction project. It took three years to advance the first 14 miles, and many more years to reach Stanley Pool. Some 132 Belgian professionals and other Europeans fell victim to accidents and pestilence. But most of the victims — at least 1,800 in the first two years alone — were the poor Congolese, toiling and dying as vassals to their “roi souverain.” The new stamps bore alternating titles, “Congo Belge” first, “Belgisch Congo” second, and bilingual references to “centimes” or “centiemen,” “francs” or “franken.” (This set remained in circulation for many years, in many permutations, as we shall see.)

steamer, hunting elephants and others. Most remarkable is a rendering of a smoke-belching engine towing cars across the M’pozo River on an elevated bridge. Remember, this design dates to the 1890s. Building the Matadi-Leopoldville railroad through the Congo was a mammoth undertaking that displayed Leopold’s relentlessness. While his stamp designers celebrated this engineering triumph, little was said about the terrible toll of this arduous railway construction project. It took three years to advance the first 14 miles, and many more years to reach Stanley Pool. Some 132 Belgian professionals and other Europeans fell victim to accidents and pestilence. But most of the victims — at least 1,800 in the first two years alone — were the poor Congolese, toiling and dying as vassals to their “roi souverain.” The new stamps bore alternating titles, “Congo Belge” first, “Belgisch Congo” second, and bilingual references to “centimes” or “centiemen,” “francs” or “franken.” (This set remained in circulation for many years, in many permutations, as we shall see.) bilingually speaking. The colony issued two identical sets of definitive stamps: one set listed “Congo Belge,” abov

bilingually speaking. The colony issued two identical sets of definitive stamps: one set listed “Congo Belge,” abov e “Belgisch Congo,” the other reversed the order. (Both sets are valued the same in catalogs; philately did not take sides in this bilingual balancing act.) In the 1950s, a two-set issue of four stamps did the same thing: one set was inscribed French

e “Belgisch Congo,” the other reversed the order. (Both sets are valued the same in catalogs; philately did not take sides in this bilingual balancing act.) In the 1950s, a two-set issue of four stamps did the same thing: one set was inscribed French  first, the other Flemish first. Take your pick. In this case, no two stamps in either set are valued the same, but I can’t discern any favoritism of one language over another. And that is about as far into the philatelic weeds as we need to go on that subject, wouldn’t you agree?

first, the other Flemish first. Take your pick. In this case, no two stamps in either set are valued the same, but I can’t discern any favoritism of one language over another. And that is about as far into the philatelic weeds as we need to go on that subject, wouldn’t you agree? as they age. First is Victoria, who appeared as completely different personae during her long reign: as a swanlike beauty in the early Chalon portraiture; a classically sculpted empress-in-profile in her middle decades; finally, as the stout dowager queen, under an elaborate headdress, gazing wistfully into the light …

as they age. First is Victoria, who appeared as completely different personae during her long reign: as a swanlike beauty in the early Chalon portraiture; a classically sculpted empress-in-profile in her middle decades; finally, as the stout dowager queen, under an elaborate headdress, gazing wistfully into the light … in 1850 of a simply dressed monarch sitting demurely on her throne. (SInce I don’t make a specialty of collecting Australia, I cannot offer a worthy sampling here. But you can find wonderful, full-color renderings of all the Victoria stamps you’d want to see — or buy — on eBay and other sites.)

in 1850 of a simply dressed monarch sitting demurely on her throne. (SInce I don’t make a specialty of collecting Australia, I cannot offer a worthy sampling here. But you can find wonderful, full-color renderings of all the Victoria stamps you’d want to see — or buy — on eBay and other sites.)

that ended in 1947. There were three portrayals of the future King Edward VIII — as a stripling laddie in 1868, a bonnie prince in 1880, and the plump, bearded embodiment of the “Edwardian age” in 1897. Isn’t it interesting to examine contemporaneous depictions of this particular Duke of Wales through the years, starting long before he began his 10-year reign at age 59 in January, 1901.

that ended in 1947. There were three portrayals of the future King Edward VIII — as a stripling laddie in 1868, a bonnie prince in 1880, and the plump, bearded embodiment of the “Edwardian age” in 1897. Isn’t it interesting to examine contemporaneous depictions of this particular Duke of Wales through the years, starting long before he began his 10-year reign at age 59 in January, 1901.

glance, to my loose-leaf album of post-1960s German stamps — when I paused. Should I just snap in the page, shelve the stock book and go on to other business? No! I determined to take a closer look at these commemoratives. After all, each one was a minor work of art, or illustration, or example of graphic artistry.

glance, to my loose-leaf album of post-1960s German stamps — when I paused. Should I just snap in the page, shelve the stock book and go on to other business? No! I determined to take a closer look at these commemoratives. After all, each one was a minor work of art, or illustration, or example of graphic artistry. ned to Wikipedia for help. Here is a brief rundown of these worthies, and the differing ways they dealt with the

ned to Wikipedia for help. Here is a brief rundown of these worthies, and the differing ways they dealt with the ashing communist j

ashing communist j ax Born (1882-1970) were brilliant physicists, close collaborators and good buddies (hence their joint appearance on the same stamp.) Franck won the Nobel Prize in 1925 for his study of electrons. Born, who won in 1954, was considered a father of quantum physics. As soon as the Nazis came to power in 1933, Franck resigned his post at the University of Goettingen in protest, and helped Jewish physicists find jobs abroad before decamping himself. After a stay in Denmark he moved to America, where he worked on the Manhattan Project. He issued a report urging that the atom bomb not be dropped on Japan without prior warning. Born wrote dozens of groundbreaking papers in Germany, but because he was Jewish, he skedaddled in 1933. He resumed his remarkable career in England, and returned to Germany in 1952.

ax Born (1882-1970) were brilliant physicists, close collaborators and good buddies (hence their joint appearance on the same stamp.) Franck won the Nobel Prize in 1925 for his study of electrons. Born, who won in 1954, was considered a father of quantum physics. As soon as the Nazis came to power in 1933, Franck resigned his post at the University of Goettingen in protest, and helped Jewish physicists find jobs abroad before decamping himself. After a stay in Denmark he moved to America, where he worked on the Manhattan Project. He issued a report urging that the atom bomb not be dropped on Japan without prior warning. Born wrote dozens of groundbreaking papers in Germany, but because he was Jewish, he skedaddled in 1933. He resumed his remarkable career in England, and returned to Germany in 1952. Josef Kentenich (1885-1968) was a Pallotine priest and founder of the Shoenstatt Movement, emphasizing service and sacrifice. Protesting against the Nazis (“I see no place where the water of Baptism could run there …”) he was arrested by the Gestapo and spent three years in the Dachau concentration camp, where he continued his work. Somehow he survived and was able to resume his benevolent work.

Josef Kentenich (1885-1968) was a Pallotine priest and founder of the Shoenstatt Movement, emphasizing service and sacrifice. Protesting against the Nazis (“I see no place where the water of Baptism could run there …”) he was arrested by the Gestapo and spent three years in the Dachau concentration camp, where he continued his work. Somehow he survived and was able to resume his benevolent work.

s a physiologist and doctor who won the Nobel Prize in 1931 for his study of the respiratory enzyme. Although his father was Jewish, Warburg was spared by the Nazis because of his key ongoing cancer research. He was officially listed as “one-half Jewish,” or maybe “one-quarter,” since the Nazis placed more emphasis on the matrilineal line. He was granted equal rights with gentiles, and stayed put — even though the Rockefeller Foundation offered him a post if he emigrated. After the war he did explore moving to America, but was turned down.

s a physiologist and doctor who won the Nobel Prize in 1931 for his study of the respiratory enzyme. Although his father was Jewish, Warburg was spared by the Nazis because of his key ongoing cancer research. He was officially listed as “one-half Jewish,” or maybe “one-quarter,” since the Nazis placed more emphasis on the matrilineal line. He was granted equal rights with gentiles, and stayed put — even though the Rockefeller Foundation offered him a post if he emigrated. After the war he did explore moving to America, but was turned down. orn in Switzerland, Barth is considered among the great Protestant theologians of the 20th century. As a professor in Bonn, he challenged the Nazis’ effort to establish a state religion. He was sacked in 1935 for refusing to swear an oath to Hitler, and returned to Switzerland for good. After the war he published an influential statement promoting both German penitence and reconciliation.

orn in Switzerland, Barth is considered among the great Protestant theologians of the 20th century. As a professor in Bonn, he challenged the Nazis’ effort to establish a state religion. He was sacked in 1935 for refusing to swear an oath to Hitler, and returned to Switzerland for good. After the war he published an influential statement promoting both German penitence and reconciliation.

s a Jewish philosopher who converted to Catholicism and became a Carmelite nun. After Hitler’s takeover, she had a premonition she would not survive the Nazis. Fearing for her safety, her order transferred her to the Netherlands. But after the Nazis occupied Holland, and Dutch bishops publicly condemned Hitler’s racism, the German occupiers rounded up all Jewish converts, like Stein, who previously had been spared. A Dutch official, impressed by her faith, offered an escape route, but she refused him, declaring her intention to “share in the fate of my brothers and sisters.” She perished in a gas chamber at Auschwitz in August, 1942. In 1987, she was beatified as St. Theresa of the Cross.

s a Jewish philosopher who converted to Catholicism and became a Carmelite nun. After Hitler’s takeover, she had a premonition she would not survive the Nazis. Fearing for her safety, her order transferred her to the Netherlands. But after the Nazis occupied Holland, and Dutch bishops publicly condemned Hitler’s racism, the German occupiers rounded up all Jewish converts, like Stein, who previously had been spared. A Dutch official, impressed by her faith, offered an escape route, but she refused him, declaring her intention to “share in the fate of my brothers and sisters.” She perished in a gas chamber at Auschwitz in August, 1942. In 1987, she was beatified as St. Theresa of the Cross. red here demonstrates how Germany atoned for its past. The inscription on the stamp includes the word “Widerstand” — resistance to Nazism between 1933 and 1945. The other word, which I had to look up — “Verfolgung” — means pursuit and persecution. Verfolgung und Widerstand — pursuit and resistance. By such redemptive acts — commemorating resistance to the Nazis, and acknowledging its trespasses and persecutions — Germany has long since reaffirmed its place of honor in the community of nations.

red here demonstrates how Germany atoned for its past. The inscription on the stamp includes the word “Widerstand” — resistance to Nazism between 1933 and 1945. The other word, which I had to look up — “Verfolgung” — means pursuit and persecution. Verfolgung und Widerstand — pursuit and resistance. By such redemptive acts — commemorating resistance to the Nazis, and acknowledging its trespasses and persecutions — Germany has long since reaffirmed its place of honor in the community of nations.

st set is strikingly exotic — engraved, with a profile portrait of George V above a stylized scene of a crocodile basking by a river with mountain peaks behind. I’m missing the higher values, but the seven-stamp partial set still makes an attractive display, don’t you think?

st set is strikingly exotic — engraved, with a profile portrait of George V above a stylized scene of a crocodile basking by a river with mountain peaks behind. I’m missing the higher values, but the seven-stamp partial set still makes an attractive display, don’t you think? Notice that I have the “universal” set of stamps rom Basutoland commemorating George V’s jubilee in 1935. As promised, they are handsome engravings of the king and Windsor Castle in regal colors: carmine and blue; gray black and ultramarine; blue and brown; bright violet and indigo. These are very familiar stamps for British Colony collectors, but still pretty.

Notice that I have the “universal” set of stamps rom Basutoland commemorating George V’s jubilee in 1935. As promised, they are handsome engravings of the king and Windsor Castle in regal colors: carmine and blue; gray black and ultramarine; blue and brown; bright violet and indigo. These are very familiar stamps for British Colony collectors, but still pretty. You see at once the contrast and similarity of the George VI definitive set and its predecessor. The design is the same: crocodile, riverbank, mountains. The portrait changes from George V to George VI, and the stamps take on a more modern cast. What makes this limited change in design interesting to a stamp collector? It relates to stately transitions and continuity. In the case of the monarchy, the lament “The King is dead!” that sounded throughout Britain in January, 1936, as George V expired, was followed in the same breath with, “Long live the King!” (Never mind that the Duke of Wales, a/k/a King Edward VIII, only stuck around for a few months before skedaddling with Wallace Simpson …) By 1938, there was a new set of stamps for sale in Maseru, Basutoland’s capital. It looked the same, but there was a fresh new face on the stamps. George VI looked handsome, resolute; very white, to be sure; very much the image of a king, under a crown, ruler of the colony.

You see at once the contrast and similarity of the George VI definitive set and its predecessor. The design is the same: crocodile, riverbank, mountains. The portrait changes from George V to George VI, and the stamps take on a more modern cast. What makes this limited change in design interesting to a stamp collector? It relates to stately transitions and continuity. In the case of the monarchy, the lament “The King is dead!” that sounded throughout Britain in January, 1936, as George V expired, was followed in the same breath with, “Long live the King!” (Never mind that the Duke of Wales, a/k/a King Edward VIII, only stuck around for a few months before skedaddling with Wallace Simpson …) By 1938, there was a new set of stamps for sale in Maseru, Basutoland’s capital. It looked the same, but there was a fresh new face on the stamps. George VI looked handsome, resolute; very white, to be sure; very much the image of a king, under a crown, ruler of the colony. The other two sets on this page deserve notice. The first consists of South African stamps overprinted for use in Basutoland, commemorating the end of World War II in 1945. Similar overprinted sets appeared in Bechuanaland Protectorate and Swaziland. This looks like an economy move for a depleted empire at the end of a brutal and costly conflict. Imagine the mixed feelings of the Basuto man-on-the-street when he discovered a new set of South African stamps (albeit overprinted) on sale at his local post office. To add insult to philatelic insurgency, the stamps are printed se-tenant (attached) both in English and Afrikaans, the language of the Boers — and apartheid.

The other two sets on this page deserve notice. The first consists of South African stamps overprinted for use in Basutoland, commemorating the end of World War II in 1945. Similar overprinted sets appeared in Bechuanaland Protectorate and Swaziland. This looks like an economy move for a depleted empire at the end of a brutal and costly conflict. Imagine the mixed feelings of the Basuto man-on-the-street when he discovered a new set of South African stamps (albeit overprinted) on sale at his local post office. To add insult to philatelic insurgency, the stamps are printed se-tenant (attached) both in English and Afrikaans, the language of the Boers — and apartheid. In 1947, the British royal family paid a visit to Africa and stopped in Basutoland. A four-stamp commemorative set was issued there and in other colonies the Royals visited. The stamps display a handsome group — King George, already looking aged but still handsome both in uniform and coat-and-tie; Queen Elizabeth, the future “Queen Mum,” elegant in her pearls; and the girls, Elizabeth and her kid sister Margaret. Not yet 21, the future queen is a pretty young woman, already striking in her composure. (Yes, these are flattering engravings, but they are excellent likenesses all the same.)

In 1947, the British royal family paid a visit to Africa and stopped in Basutoland. A four-stamp commemorative set was issued there and in other colonies the Royals visited. The stamps display a handsome group — King George, already looking aged but still handsome both in uniform and coat-and-tie; Queen Elizabeth, the future “Queen Mum,” elegant in her pearls; and the girls, Elizabeth and her kid sister Margaret. Not yet 21, the future queen is a pretty young woman, already striking in her composure. (Yes, these are flattering engravings, but they are excellent likenesses all the same.) Note the empty spaces for the Silver Wedding set, another “universal” issue throughout the colonies. I don’t have many of these sets, for a couple of reasons: 1) The set is freakishly priced, with a cheap and virtually valueless low-denomination stamp, and a top-value companion — a deterrent to this young stamp collector. 2) The stamps are pretty boring, even though the high-value one is a handsomely engraved double portrait of George VI and Elizabeth in profile (the lower value is usually lithographed). 3) Notwithstanding their high combined face value, the sets are not hard to find or prohibitively expensive, suggesting they are not widely popular or in demand. 4) Even in his engraved portrait, George can’t hide how poorly he’s doing, which is kind of a downer. In short, this set seemed dull, even a bit creepy. I tended to avoid it, spending my precious savings

Note the empty spaces for the Silver Wedding set, another “universal” issue throughout the colonies. I don’t have many of these sets, for a couple of reasons: 1) The set is freakishly priced, with a cheap and virtually valueless low-denomination stamp, and a top-value companion — a deterrent to this young stamp collector. 2) The stamps are pretty boring, even though the high-value one is a handsomely engraved double portrait of George VI and Elizabeth in profile (the lower value is usually lithographed). 3) Notwithstanding their high combined face value, the sets are not hard to find or prohibitively expensive, suggesting they are not widely popular or in demand. 4) Even in his engraved portrait, George can’t hide how poorly he’s doing, which is kind of a downer. In short, this set seemed dull, even a bit creepy. I tended to avoid it, spending my precious savings  elsewhere.

elsewhere. days. You’ll notice that the colonial stamp producers did not choose to continue the set with the alligator for Elizabeth, even though they kept up a common design for definitives in Bechuanaland Protectorate, to the north, and in other colonies. Maybe they considered a sharp-toothed croc an inappropriate companion, lurking beneath the comely young queen. It’s not like the crocodile is the colony’s badge or anything. So they broke with tradition and gave Basutoland a brand-new set. And look what they came up with! Even this short set is gorgeous. I have had many happy moments mooning over the finely engraved scenes that peek out through the decorative borders. In each stamp there is an engraved cameo profile of the queen under her crown, presiding with benign attentiveness. The contrasting colors are daring: orange and deep blue; carmine and olive green; deep blue and indigo …