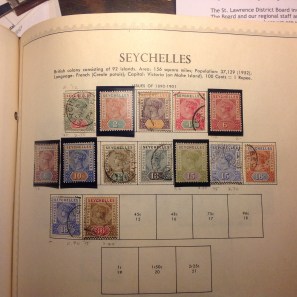

Page One: Issues of 1933-37

Basutoland/Lesotho is a small, somewhat improbable country. Its high, arid plains are entirely surrounded by South Africa. It owes its existence as much as anything to its remoteness, and to its tribal king. Moshoeshoe was a charismatic leader and skilled diplomat whose reign extended from 1820 some 50 years, three decades-plus into the Victorian era. Basutoland was variously claimed and manhandled by the British, the Cape Colony, the Boers from Orange Free State and Griqualand, the Zulu and other warring neighbors. Basuto tribes fought among themselves but somehow, emerged intact as a nation under King Moshoeshoe. They resisted incorporation into South Africa in 1910, rejecting the apartheid model, and survived as a protectorate and colony of Great Britain. British rule was relatively light and supple. Central administration was under a resident commissioner. Tribal leaders ran things legislatively under a paramount chief, with a high court convening when needed. Basutoland got its first elected legislature in 1959, and became the independent state of Lesotho in 1965. (Don’t confuse Basutoland — or Lesotho — with those phony-baloney South African “homelands.” The vassal states of Transkei, Venda, Ciskei and Bophutatswana were bogus from Day One — though they did issue some beautiful stamps that continue to be listed in the Scott catalog.)

This cover, captured from the Internet, displays stamps from southern Africa that were valid for postage throughout the Union of South Africa through 1937: Basutoland, Transvaal, South Africa, Orange River Colony, Natal and Cape of Good Hope.

Why didn’t Basutoland get its own stamps until 1933? (I don’t yet know.) Whose stamps did local folks use to mail their letters before then? Stamps of South Africa, for sure, and from Cape of Good Hope and elsewhere. All the surrounding postal authorities of earlier years— Natal, Transvaal, Orange River Colony, Zululand, Cape Colony — were using stamps of the South African “union” after 1910. Basutoland, a separate and distinct British colony, continued to borrow its stamps for 23 years. How odd. As it happened, older stamps from Cape of Good Hope, Transvaal, Natal and Orange River Colony remained valid for postage throughout South Africa until 1937, so Basutos could take their pick. This envelope from Maseru (right, above), postmarked in 1933, shows stamps from, left to right: Basutoland, Transvaal, South Africa, Orange River Colony, Natal and Cape of Good Hope.

Basutoland’s fir st set is strikingly exotic — engraved, with a profile portrait of George V above a stylized scene of a crocodile basking by a river with mountain peaks behind. I’m missing the higher values, but the seven-stamp partial set still makes an attractive display, don’t you think?

st set is strikingly exotic — engraved, with a profile portrait of George V above a stylized scene of a crocodile basking by a river with mountain peaks behind. I’m missing the higher values, but the seven-stamp partial set still makes an attractive display, don’t you think?

Notice that I have the “universal” set of stamps rom Basutoland commemorating George V’s jubilee in 1935. As promised, they are handsome engravings of the king and Windsor Castle in regal colors: carmine and blue; gray black and ultramarine; blue and brown; bright violet and indigo. These are very familiar stamps for British Colony collectors, but still pretty.

Notice that I have the “universal” set of stamps rom Basutoland commemorating George V’s jubilee in 1935. As promised, they are handsome engravings of the king and Windsor Castle in regal colors: carmine and blue; gray black and ultramarine; blue and brown; bright violet and indigo. These are very familiar stamps for British Colony collectors, but still pretty.

Page Two: Issues of 1938-47

You see at once the contrast and similarity of the George VI definitive set and its predecessor. The design is the same: crocodile, riverbank, mountains. The portrait changes from George V to George VI, and the stamps take on a more modern cast. What makes this limited change in design interesting to a stamp collector? It relates to stately transitions and continuity. In the case of the monarchy, the lament “The King is dead!” that sounded throughout Britain in January, 1936, as George V expired, was followed in the same breath with, “Long live the King!” (Never mind that the Duke of Wales, a/k/a King Edward VIII, only stuck around for a few months before skedaddling with Wallace Simpson …) By 1938, there was a new set of stamps for sale in Maseru, Basutoland’s capital. It looked the same, but there was a fresh new face on the stamps. George VI looked handsome, resolute; very white, to be sure; very much the image of a king, under a crown, ruler of the colony.

You see at once the contrast and similarity of the George VI definitive set and its predecessor. The design is the same: crocodile, riverbank, mountains. The portrait changes from George V to George VI, and the stamps take on a more modern cast. What makes this limited change in design interesting to a stamp collector? It relates to stately transitions and continuity. In the case of the monarchy, the lament “The King is dead!” that sounded throughout Britain in January, 1936, as George V expired, was followed in the same breath with, “Long live the King!” (Never mind that the Duke of Wales, a/k/a King Edward VIII, only stuck around for a few months before skedaddling with Wallace Simpson …) By 1938, there was a new set of stamps for sale in Maseru, Basutoland’s capital. It looked the same, but there was a fresh new face on the stamps. George VI looked handsome, resolute; very white, to be sure; very much the image of a king, under a crown, ruler of the colony.

Consistency is a profound value in philately. Art and meaning flow through order. Philately is deeply conservative in its reverence for a certain kind of order. It quietly celebrates vitality, artistry, decoration, contrast — within strict confines of stamp design, utility, sequence and value. Letter carriers on their appointed rounds are a sign of an orderly, peaceful nation; so, too, stamps on the envelopes they deliver are emblems of order and normality. (There are exceptions, of course, which make the hobby even more fun!)

The similarity and contrasts within and between stamps, as well as between sets, provide visual pleasure as well as social, cultural and political clues. In this case, the smooth transition from George V to George VI (after the unpleasantness over young Edward) is reflected in these two subtly different definitive sets. Together, they signal an unbroken bond of colonial protection (and dominion) — adroitly managed by the mandarins of the colonial office at Whitehall.

The other two sets on this page deserve notice. The first consists of South African stamps overprinted for use in Basutoland, commemorating the end of World War II in 1945. Similar overprinted sets appeared in Bechuanaland Protectorate and Swaziland. This looks like an economy move for a depleted empire at the end of a brutal and costly conflict. Imagine the mixed feelings of the Basuto man-on-the-street when he discovered a new set of South African stamps (albeit overprinted) on sale at his local post office. To add insult to philatelic insurgency, the stamps are printed se-tenant (attached) both in English and Afrikaans, the language of the Boers — and apartheid.

The other two sets on this page deserve notice. The first consists of South African stamps overprinted for use in Basutoland, commemorating the end of World War II in 1945. Similar overprinted sets appeared in Bechuanaland Protectorate and Swaziland. This looks like an economy move for a depleted empire at the end of a brutal and costly conflict. Imagine the mixed feelings of the Basuto man-on-the-street when he discovered a new set of South African stamps (albeit overprinted) on sale at his local post office. To add insult to philatelic insurgency, the stamps are printed se-tenant (attached) both in English and Afrikaans, the language of the Boers — and apartheid.

In 1947, the British royal family paid a visit to Africa and stopped in Basutoland. A four-stamp commemorative set was issued there and in other colonies the Royals visited. The stamps display a handsome group — King George, already looking aged but still handsome both in uniform and coat-and-tie; Queen Elizabeth, the future “Queen Mum,” elegant in her pearls; and the girls, Elizabeth and her kid sister Margaret. Not yet 21, the future queen is a pretty young woman, already striking in her composure. (Yes, these are flattering engravings, but they are excellent likenesses all the same.)

In 1947, the British royal family paid a visit to Africa and stopped in Basutoland. A four-stamp commemorative set was issued there and in other colonies the Royals visited. The stamps display a handsome group — King George, already looking aged but still handsome both in uniform and coat-and-tie; Queen Elizabeth, the future “Queen Mum,” elegant in her pearls; and the girls, Elizabeth and her kid sister Margaret. Not yet 21, the future queen is a pretty young woman, already striking in her composure. (Yes, these are flattering engravings, but they are excellent likenesses all the same.)

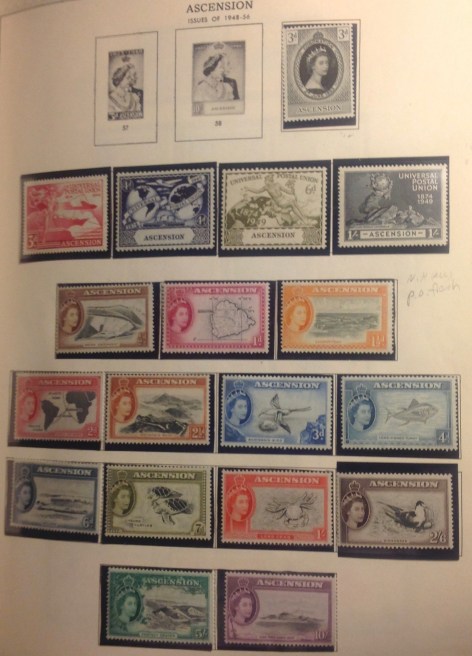

Page Three: Issues of 1948-54

Note the empty spaces for the Silver Wedding set, another “universal” issue throughout the colonies. I don’t have many of these sets, for a couple of reasons: 1) The set is freakishly priced, with a cheap and virtually valueless low-denomination stamp, and a top-value companion — a deterrent to this young stamp collector. 2) The stamps are pretty boring, even though the high-value one is a handsomely engraved double portrait of George VI and Elizabeth in profile (the lower value is usually lithographed). 3) Notwithstanding their high combined face value, the sets are not hard to find or prohibitively expensive, suggesting they are not widely popular or in demand. 4) Even in his engraved portrait, George can’t hide how poorly he’s doing, which is kind of a downer. In short, this set seemed dull, even a bit creepy. I tended to avoid it, spending my precious savings

Note the empty spaces for the Silver Wedding set, another “universal” issue throughout the colonies. I don’t have many of these sets, for a couple of reasons: 1) The set is freakishly priced, with a cheap and virtually valueless low-denomination stamp, and a top-value companion — a deterrent to this young stamp collector. 2) The stamps are pretty boring, even though the high-value one is a handsomely engraved double portrait of George VI and Elizabeth in profile (the lower value is usually lithographed). 3) Notwithstanding their high combined face value, the sets are not hard to find or prohibitively expensive, suggesting they are not widely popular or in demand. 4) Even in his engraved portrait, George can’t hide how poorly he’s doing, which is kind of a downer. In short, this set seemed dull, even a bit creepy. I tended to avoid it, spending my precious savings  elsewhere.

elsewhere.

The next set celebrates the International Postal Union’s 75h anniversary in 1949. At first glance you may dismiss this as a rather ho-hum; each stamp is mono-color, kind of busy-looking. None of these “universal” UPU sets are worth much. That said, they do merit a closer look. There are four detailed, expert engravings of allegorical scenes: Two show Mercury on his rounds; another depicts a plane and steamship circumnavigating the hemispheres. The most fanciful design has a queenly figure sitting amid a throne of rocks, while a band of seraphim join hands around a globe that is being mysteriously propelled through space, trailing a thick cloud. (This last design is a rendering of the UPU monument at its headquarters in Bern, Switzerland. Check it out online.)

The obligatory Elizabeth II coronation stamp appears at the top of the page. Notice how queenly she looks, transformed from the vignettes of her pre-royalty days to the same kind of Swanlike beauty of Victoria’s Chalon portrait.

Rounding out the page is the definitive set of 1954 (above). This is a beauty, even though I’m still missing the top values, which would cost me upwards of $30 these  days. You’ll notice that the colonial stamp producers did not choose to continue the set with the alligator for Elizabeth, even though they kept up a common design for definitives in Bechuanaland Protectorate, to the north, and in other colonies. Maybe they considered a sharp-toothed croc an inappropriate companion, lurking beneath the comely young queen. It’s not like the crocodile is the colony’s badge or anything. So they broke with tradition and gave Basutoland a brand-new set. And look what they came up with! Even this short set is gorgeous. I have had many happy moments mooning over the finely engraved scenes that peek out through the decorative borders. In each stamp there is an engraved cameo profile of the queen under her crown, presiding with benign attentiveness. The contrasting colors are daring: orange and deep blue; carmine and olive green; deep blue and indigo …

days. You’ll notice that the colonial stamp producers did not choose to continue the set with the alligator for Elizabeth, even though they kept up a common design for definitives in Bechuanaland Protectorate, to the north, and in other colonies. Maybe they considered a sharp-toothed croc an inappropriate companion, lurking beneath the comely young queen. It’s not like the crocodile is the colony’s badge or anything. So they broke with tradition and gave Basutoland a brand-new set. And look what they came up with! Even this short set is gorgeous. I have had many happy moments mooning over the finely engraved scenes that peek out through the decorative borders. In each stamp there is an engraved cameo profile of the queen under her crown, presiding with benign attentiveness. The contrasting colors are daring: orange and deep blue; carmine and olive green; deep blue and indigo …

I sent a money order to Maseru from Heidelberg in 1962, and narrowly missed receiving these definitive stamps by return mail. (The short set I display here must have come from a stamp store.) Here’s what happened instead. In 1961, Basutoland abandoned sterling currency for decimals — cents and rands — along with South Africa and other neighbors. What the postal authorities sent back to me from Basutoland, in an official brown envelope marked ”On Her Majesty’s Service,” was a new set, one that heralded a new adventure for me in stamp collecting.

Page Four: Issues of 1956-61

Before I address the main excitement of this page — the definitive series surcharged in decimal currency — I will comment briefly on the other sets on the page. In  addition to the two “postage due” stamps (which I don’t have) and a single 2d stamp surcharged 1/2d (there must have been a shortage of the 1/2d definitive), there is a nicely engraved, three-stamp set commemorating the creation of Basutoland’s new legislature, the National Council, in 1959. The first stamp recognizes the “Laws of Moshesh 1854,” with a likeness of long-reigning King Moshoeshoe. (There seem to be numerous spellings of his name.) The second depicts a modest building and the caption “Basutoland Council 1903,” referring to what passed for a local deliberative assembly more than a century ago. The third stamp shows a pipe-smoking Mosotho tribesman on horseback, with his distinctive robe and peaked hat (Is that a dove with an olive branch flying behind him? A swallow with a twig for its nest? An airplane?) In case you are wondering, none of these stamps is valuable.

addition to the two “postage due” stamps (which I don’t have) and a single 2d stamp surcharged 1/2d (there must have been a shortage of the 1/2d definitive), there is a nicely engraved, three-stamp set commemorating the creation of Basutoland’s new legislature, the National Council, in 1959. The first stamp recognizes the “Laws of Moshesh 1854,” with a likeness of long-reigning King Moshoeshoe. (There seem to be numerous spellings of his name.) The second depicts a modest building and the caption “Basutoland Council 1903,” referring to what passed for a local deliberative assembly more than a century ago. The third stamp shows a pipe-smoking Mosotho tribesman on horseback, with his distinctive robe and peaked hat (Is that a dove with an olive branch flying behind him? A swallow with a twig for its nest? An airplane?) In case you are wondering, none of these stamps is valuable.

Now, on to the decimal overprints. Why did I go wild with (muted) excitement over a set like this? Partly because it seemed so … provisional, so … well, wild. Surcharging stamps was an awkward process that marred the purity of the design and created confusion as to its correct value. The surcharge defaced the original stamp, rendering it instantly obsolete. When the surcharge included a change from British sterling to decimal value, things could get particularly confusing. In Canada, the Seychelles and elsewhere, the transition came in the 1800s. A few early (and valuable) Canadian  stamps are denominated both in “cents” and the old “st’ling.” Another wave of conversions to decimal came before World War II in Caribbean colonies. The nadir of the surcharge business came with those hapless stamps that received two surcharges, one supposedly cancelling out the other — thus leaving the poor customer (and postal clerk) to contend with three separate values on a single stamp. Surcharges were a confusing bother to postal officials and the general public, and were yanked as soon as a new, “proper” set of definitives could be printed. Once the surcharged stamps were taken out of circulation, they sometimes jumped in value to collectors.

stamps are denominated both in “cents” and the old “st’ling.” Another wave of conversions to decimal came before World War II in Caribbean colonies. The nadir of the surcharge business came with those hapless stamps that received two surcharges, one supposedly cancelling out the other — thus leaving the poor customer (and postal clerk) to contend with three separate values on a single stamp. Surcharges were a confusing bother to postal officials and the general public, and were yanked as soon as a new, “proper” set of definitives could be printed. Once the surcharged stamps were taken out of circulation, they sometimes jumped in value to collectors.

Examine the surcharge on these stamps closely: Some of numbers appear thicker than others. It turns out three distinct types of surcharges were used in this set. Which to my mind, makes these stamps even wilder! Type I was thicker than Type II; Type III, used only for the 1-rand stamp, consisted of tall, narrow figures. Some of these varieties now command a premium, though most are affordable. A few stamps carry “inverted” (upside down) surcharges. These “errors” occurred on the 2 cent stamp (costing hundreds of dollars today) and the 2 1/2 cent (worth more than $1,000). Alas, there are no rare varieties among the stamps I received from Maseru in 1962. Nor have I tried to find surcharge varieties — though I’ve often thought it would be fun. This “surcharge” adventure continued with stamps from Bechuanaland (where I also sent a money order) and Swaziland; both countries adopted decimal currency the same time as Basutoland and South Africa.

Page Five: Issues of 1961-3

Sure enough, along came the “new” definitive series with decimal currency. In this case, Basutoland got the same splendid Elizabeth II set first issued in 1954, with decimal values in place of pence and shillings. The brilliantly etched vignettes and borders are restored to their full glory. My set is complete. A pencil note states I bought it in 1991 for $11.50. Today, the set goes for $45 on zillionsofstamps.com. Not a bad

Sure enough, along came the “new” definitive series with decimal currency. In this case, Basutoland got the same splendid Elizabeth II set first issued in 1954, with decimal values in place of pence and shillings. The brilliantly etched vignettes and borders are restored to their full glory. My set is complete. A pencil note states I bought it in 1991 for $11.50. Today, the set goes for $45 on zillionsofstamps.com. Not a bad  investment, eh?

investment, eh?

Also on this page is the “universal” Red Cross centenary set. Above it is space for the “freedom from hunger” universal stamp. The five-cent surcharge on an old (1930s era) postage due stamp costs several dollars today, if you could find it.

Basutoland would issue a few more stamps through 1965, including a set oddly inscribed with both “Basutoland” and “Lesotho,” marking the attainment of self-government. (How can a country have two names?) In contrast to the stately march from one  colonial monarch to the next, the transition of British colonies to independence was seldom smooth — politically, economically socially or symbolically — and this was reflected philatelically, in unforeseen developments and awkward moments, odd stamp issues, false starts, dramatic turns, printing errors, other calamities and incongruities to match the times. — as you will see …

colonial monarch to the next, the transition of British colonies to independence was seldom smooth — politically, economically socially or symbolically — and this was reflected philatelically, in unforeseen developments and awkward moments, odd stamp issues, false starts, dramatic turns, printing errors, other calamities and incongruities to match the times. — as you will see …

Before departing from Basutoland, enjoy a few last closeups of that artful set, first issued in 1954.

Before departing from Basutoland, enjoy a few last closeups of that artful set, first issued in 1954.

nsists of stamps of St. Helena, another British possession 800 miles to the southeast, overprinted “Ascension.” One wonders how local inhabitants reacted to stamps depicting a faraway island, intended to represent them in the wide world. How humiliating … Mercifully, it took only two years — from 1922 to 1924 — for colonial stamp designers to come up with an original set for Ascension, displaying the Badge of the Colony.

nsists of stamps of St. Helena, another British possession 800 miles to the southeast, overprinted “Ascension.” One wonders how local inhabitants reacted to stamps depicting a faraway island, intended to represent them in the wide world. How humiliating … Mercifully, it took only two years — from 1922 to 1924 — for colonial stamp designers to come up with an original set for Ascension, displaying the Badge of the Colony. he stamps are wide and tall, with artistic engravings of Georgetown, Long Beach, a map of the remote South Atlantic island and other scenes. The vignettes are printed in black, as is the profile of the king. The borders are intense colors — violet, green, ultramarine, orange … The contrast is striking, and the fine designs of the engraver’s art resonate back and forth between the dark centers and portrait on each stamp and the succession of bright colors on the borders. This set is cancelled, missing the higher values —an attractive work-in-progress.

he stamps are wide and tall, with artistic engravings of Georgetown, Long Beach, a map of the remote South Atlantic island and other scenes. The vignettes are printed in black, as is the profile of the king. The borders are intense colors — violet, green, ultramarine, orange … The contrast is striking, and the fine designs of the engraver’s art resonate back and forth between the dark centers and portrait on each stamp and the succession of bright colors on the borders. This set is cancelled, missing the higher values —an attractive work-in-progress. ed artistry and design integrity. The stamps are laid out in orderly rows, set off by their black protective mounts. They hint at considerable value even as they please the eyes and stimulate the imagination. This is the George VI definitive set, mint and complete. In this case, “complete” means a full complement of 15 stamps, from a half-penny to 10 shillings. (Never mind the blank space on the page of the Minkus album; the authoritative Scott catalog affirms the set’s completeness, ignoring the suspect “yellow orange & lilac” 1 1/2d value cited by Minkus.)

ed artistry and design integrity. The stamps are laid out in orderly rows, set off by their black protective mounts. They hint at considerable value even as they please the eyes and stimulate the imagination. This is the George VI definitive set, mint and complete. In this case, “complete” means a full complement of 15 stamps, from a half-penny to 10 shillings. (Never mind the blank space on the page of the Minkus album; the authoritative Scott catalog affirms the set’s completeness, ignoring the suspect “yellow orange & lilac” 1 1/2d value cited by Minkus.) Please indulge a little esoterica here — a comment on the unusual number of color changes in this set. There were

Please indulge a little esoterica here — a comment on the unusual number of color changes in this set. There were black. One can imagine a bit of confusion when the black-only 3d stamp replaced the black-and-blue 3d in 194

black. One can imagine a bit of confusion when the black-only 3d stamp replaced the black-and-blue 3d in 194 You may notice if you squint that below some stamps on the pages of my albums there are tiny penciled inscriptions: date and amount paid, for the most part. I began doing this a decade or more ago, noting prices paid above $2. (The most I have paid so far for a stamp is $105 for an embossed stamp from Natal, circa 1857.) This notation system should help me or my heirs when it comes time to tote up the cash value of my collection, at least from the standpoint of my own expenditures. I’m sure it’s already in the thousands …

You may notice if you squint that below some stamps on the pages of my albums there are tiny penciled inscriptions: date and amount paid, for the most part. I began doing this a decade or more ago, noting prices paid above $2. (The most I have paid so far for a stamp is $105 for an embossed stamp from Natal, circa 1857.) This notation system should help me or my heirs when it comes time to tote up the cash value of my collection, at least from the standpoint of my own expenditures. I’m sure it’s already in the thousands … The page rounds out with another Common Design set, this one to commemorate the end of World War II. The two mono-color stamps contain a new, face-on portrait of the king, looking calm, resolute, well-turned-out and handsome as ever. Next to him is an impressive engraved rendering of the Houses of Parliament reflected in the Thames. While this set, like the coronation set, never became valuable, it’s easy to imagine what an important purpose the stamps served. At the end of this punishing war, it announced that Britain was still a commanding presence — solid, secure, orderly, reassuring, a monumental edifice firmly planted at the center of the empire.

The page rounds out with another Common Design set, this one to commemorate the end of World War II. The two mono-color stamps contain a new, face-on portrait of the king, looking calm, resolute, well-turned-out and handsome as ever. Next to him is an impressive engraved rendering of the Houses of Parliament reflected in the Thames. While this set, like the coronation set, never became valuable, it’s easy to imagine what an important purpose the stamps served. At the end of this punishing war, it announced that Britain was still a commanding presence — solid, secure, orderly, reassuring, a monumental edifice firmly planted at the center of the empire. ry of George VI and Queen Mary in 1948, the coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953, and the four-stamp set commemorating the 78th anniversary of the Universal Postal Union (see below), were occasions for more “universal” issues. (I will say more about the Silver Wedding and UPU sets later). The same designs were in circulation in virtually every colony. The engraved portrait of HM Elizabeth II brings out her youthful beauty. Barely out of her teens, she seems serene and confident as she begins her reign over the final incarnation of “a greater empire than has been.”

ry of George VI and Queen Mary in 1948, the coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953, and the four-stamp set commemorating the 78th anniversary of the Universal Postal Union (see below), were occasions for more “universal” issues. (I will say more about the Silver Wedding and UPU sets later). The same designs were in circulation in virtually every colony. The engraved portrait of HM Elizabeth II brings out her youthful beauty. Barely out of her teens, she seems serene and confident as she begins her reign over the final incarnation of “a greater empire than has been.” Majesty’s Service,” addressed to 13-year-old me! Here is a rare photo recording the arrival of one such packet — perhaps from Ascension. The household gathered at the front door of Philosophenweg 9 in Heidelberg to bear witness as FMF received and opened his postal letter. It was such a memorable event, the postman stuck around for the occasion. Mother served cookies and lemonade for the occasion.

Majesty’s Service,” addressed to 13-year-old me! Here is a rare photo recording the arrival of one such packet — perhaps from Ascension. The household gathered at the front door of Philosophenweg 9 in Heidelberg to bear witness as FMF received and opened his postal letter. It was such a memorable event, the postman stuck around for the occasion. Mother served cookies and lemonade for the occasion. t adventures in international post-office shopping, I got lucky with the envelope containing my stamps. The kindly postmaster affixed a complete set up to the one-shilling value on the cover, making it a pretty and desirable showpiece in itself. … They may well be the cover I am opening in the dramatic scene photographed above, which would make the date June 6, 1962. How can I be so sure of the date? Because as you will note on the envelope’s display page, I recorded how long it took for my letter to get to Ascension and back. (The dates are presented European-style: day first, then month, then year.) This kind of compulsive data-keeping is typical of stamp-collecting, I think: mildly significant, moderately useful, slightly esoteric … not altogether boring …

t adventures in international post-office shopping, I got lucky with the envelope containing my stamps. The kindly postmaster affixed a complete set up to the one-shilling value on the cover, making it a pretty and desirable showpiece in itself. … They may well be the cover I am opening in the dramatic scene photographed above, which would make the date June 6, 1962. How can I be so sure of the date? Because as you will note on the envelope’s display page, I recorded how long it took for my letter to get to Ascension and back. (The dates are presented European-style: day first, then month, then year.) This kind of compulsive data-keeping is typical of stamp-collecting, I think: mildly significant, moderately useful, slightly esoteric … not altogether boring …

and accompanying note that I hope helps to explain why we stamp collectors get enthusiastic about our hobby …

and accompanying note that I hope helps to explain why we stamp collectors get enthusiastic about our hobby … our other stamp quartets in the Americana series, up to the top $5 value. The sayings that circle round the stamps unite each quadrant, and the five quadrants form their own circle, united by their design and content.

our other stamp quartets in the Americana series, up to the top $5 value. The sayings that circle round the stamps unite each quadrant, and the five quadrants form their own circle, united by their design and content. Europe (red dust cover, or should I say, magenta?). One reason why I don’t store these albums next to each other is that the thinner albums immediately to the right of each one contain newer stamps (1960s on) from each area of the world, including the last colonial stamps as well as post-independence issues.

Europe (red dust cover, or should I say, magenta?). One reason why I don’t store these albums next to each other is that the thinner albums immediately to the right of each one contain newer stamps (1960s on) from each area of the world, including the last colonial stamps as well as post-independence issues. overs” like this one, with stamps placed on specially engraved envelopes and cancelled on the first day of issue. These covers were supposed to become collector’s items, but it hasn’t turned out that way, to the chagrin of first-day cover enthusiasts. Today FDCs are a glut on the market …

overs” like this one, with stamps placed on specially engraved envelopes and cancelled on the first day of issue. These covers were supposed to become collector’s items, but it hasn’t turned out that way, to the chagrin of first-day cover enthusiasts. Today FDCs are a glut on the market … nvelopes sent through the mail before the advent of U.S. postage stamps in 1847 — for example, this one bearing a postmark of 1844 (see date in small type at left); another is from 1840. There are some envelopes with early American stamps, others with Confederate stamps from the 1860s (see below). They may be worth something, but probably not much. …

nvelopes sent through the mail before the advent of U.S. postage stamps in 1847 — for example, this one bearing a postmark of 1844 (see date in small type at left); another is from 1840. There are some envelopes with early American stamps, others with Confederate stamps from the 1860s (see below). They may be worth something, but probably not much. … Another type of cover is the specially cancelled “first flight” envelope bearing an early airmail stamp. For example, this envelope was carried on the first stamped-mail flight from Miami (and Virgin Isla

Another type of cover is the specially cancelled “first flight” envelope bearing an early airmail stamp. For example, this envelope was carried on the first stamped-mail flight from Miami (and Virgin Isla nds?) to New York City on Jan. 9, 1929. Some “first flight” covers are valuable. And romantic! The rarest cover in my collection is one addressed to my Uncle Reddy, in Needham, Mass. (see below). It bears the 24-cent “Jenny” airmail stamp, cancelled with the message: “Air Mail Service; New York; Jun 3, 1918; First Trip.” A rubber stamp in the lower left corner of the envelope announces: “VIA Aeroplane Mail.” Quaint! While the envelope isn’t in particularly good shape, a similar cover was offered on eBay recently — for $250!

nds?) to New York City on Jan. 9, 1929. Some “first flight” covers are valuable. And romantic! The rarest cover in my collection is one addressed to my Uncle Reddy, in Needham, Mass. (see below). It bears the 24-cent “Jenny” airmail stamp, cancelled with the message: “Air Mail Service; New York; Jun 3, 1918; First Trip.” A rubber stamp in the lower left corner of the envelope announces: “VIA Aeroplane Mail.” Quaint! While the envelope isn’t in particularly good shape, a similar cover was offered on eBay recently — for $250! You do know the difference between a stamp album and a stock book, don’t you? Do I have to explain everything? Oh, all right. Take my American collection, which starts with a binder full of pages offering spaces for every major variety of U.S. stamp … from the first two in 1847 — the Benjamin Franklin 5-cent and the George Washington 10 cent — until the pages run out in the 1960s. Beyond that date — now more than a half-century ago! — I have relied on stock book pages to hold my U.S. stamps. A typical stock book page has up to 10 plastic or parchment strips arrayed in parallel rows, Each strip is attached to the page at the sides and across the bottom, thus creating a secure holder for up to a half-dozen stamps inserted (using stamp tongs, of course!) across the width of the strip. Space out the stamps in your own design, or bunch them up for bulk or “stock” storage (hence the name “stock” book). I have numerous small stock books loaded with duplicate stamps, many of them cancelled. You must take care when the stamps are uncancelled, or “mint.” Allow humidity into a room where mint stamps are stored on top of each other in stock books, and you could have a real sticky problem!

You do know the difference between a stamp album and a stock book, don’t you? Do I have to explain everything? Oh, all right. Take my American collection, which starts with a binder full of pages offering spaces for every major variety of U.S. stamp … from the first two in 1847 — the Benjamin Franklin 5-cent and the George Washington 10 cent — until the pages run out in the 1960s. Beyond that date — now more than a half-century ago! — I have relied on stock book pages to hold my U.S. stamps. A typical stock book page has up to 10 plastic or parchment strips arrayed in parallel rows, Each strip is attached to the page at the sides and across the bottom, thus creating a secure holder for up to a half-dozen stamps inserted (using stamp tongs, of course!) across the width of the strip. Space out the stamps in your own design, or bunch them up for bulk or “stock” storage (hence the name “stock” book). I have numerous small stock books loaded with duplicate stamps, many of them cancelled. You must take care when the stamps are uncancelled, or “mint.” Allow humidity into a room where mint stamps are stored on top of each other in stock books, and you could have a real sticky problem! or a stamp is $105, a princely sum which I paid in 2013 for Natal No. 1, 3 pence, rose, 1857 (pictured here, larger than actual size). The stamp has a catalog value over $500, but that is for a copy with four clear margins, whereas my copy has only three. I have no certificate of authenticity, and there are known to be reprints with bogus cancellations. Nevertheless, I am fairly certain this is the real deal. Now, if you’re just skimming over the album page, you might be tempted to dismiss this rarity. It looks like a smudged square of colored paper with some bumps on it. Look more closely, though, and you will see a clear impression saying “THREE PENCE,” much of it picked up by the bla

or a stamp is $105, a princely sum which I paid in 2013 for Natal No. 1, 3 pence, rose, 1857 (pictured here, larger than actual size). The stamp has a catalog value over $500, but that is for a copy with four clear margins, whereas my copy has only three. I have no certificate of authenticity, and there are known to be reprints with bogus cancellations. Nevertheless, I am fairly certain this is the real deal. Now, if you’re just skimming over the album page, you might be tempted to dismiss this rarity. It looks like a smudged square of colored paper with some bumps on it. Look more closely, though, and you will see a clear impression saying “THREE PENCE,” much of it picked up by the bla ck ink of the cancellation. Actually, the margins are unusually large for this variety: just in at the bottom, clear the rest of the way around. Compare the faint embossing on the stamp with the actual design outline, at right, as presented in the Scott stamp catalogue, and you may be able to discern details on the original:: 1) as stated, the number is clear under the postal strike; 2) also visible are the circular border and the letter “A” from Natal at top; 3) “V” is visible at left, and a faint “R” at right. Can you see it? Now think of this odd stamp, embossed more than 150 years ago, placed on an envelope in the new south African colony of Natal for the outgoing mail. Now That stamp is in my collection. As you might suspect, I have examined this stamp in great detail, and confess to be being hypnotized in looking at it — something about the fleshy color, the tattoo-like embossing, the nearly hidden letters and symbols, then imagining this artifact making its way from that African postal outpost back in 1857 … philately just boggles the mind!

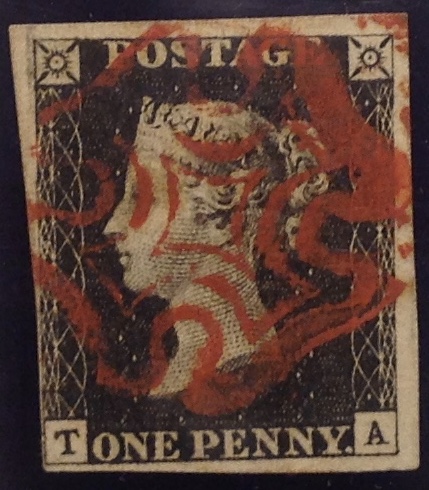

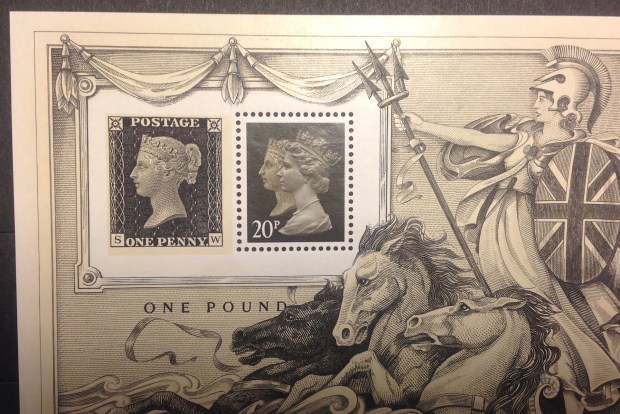

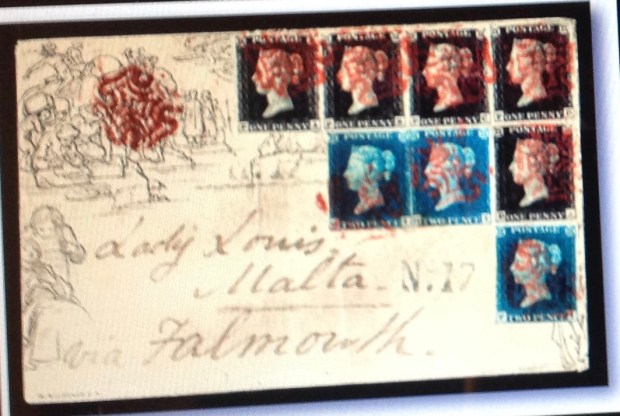

ck ink of the cancellation. Actually, the margins are unusually large for this variety: just in at the bottom, clear the rest of the way around. Compare the faint embossing on the stamp with the actual design outline, at right, as presented in the Scott stamp catalogue, and you may be able to discern details on the original:: 1) as stated, the number is clear under the postal strike; 2) also visible are the circular border and the letter “A” from Natal at top; 3) “V” is visible at left, and a faint “R” at right. Can you see it? Now think of this odd stamp, embossed more than 150 years ago, placed on an envelope in the new south African colony of Natal for the outgoing mail. Now That stamp is in my collection. As you might suspect, I have examined this stamp in great detail, and confess to be being hypnotized in looking at it — something about the fleshy color, the tattoo-like embossing, the nearly hidden letters and symbols, then imagining this artifact making its way from that African postal outpost back in 1857 … philately just boggles the mind! th you now (more will be presented in future chapters) is the Penny Black from Great Britain. This is the First Stamp, issued in 1840, bearing the engraved profile of Queen Victoria. It was produced by Sir Rowland Hill. This stamp cost me $70 in 1991. The Penny Black is not exceedingly rare, but very old. Mint copies (uncancelled) are expensive. But used examples with nice cancellations and four margins — that is, where you can see white all the way around the design — can bring hundreds. Mine has four margins, or so I claim. You may need a magnifying glass to discern the thin sliver of white that continues around the lower left of the stamp — but I maintain it is there! Thus I believe my stamp should be worth at least — $70!

th you now (more will be presented in future chapters) is the Penny Black from Great Britain. This is the First Stamp, issued in 1840, bearing the engraved profile of Queen Victoria. It was produced by Sir Rowland Hill. This stamp cost me $70 in 1991. The Penny Black is not exceedingly rare, but very old. Mint copies (uncancelled) are expensive. But used examples with nice cancellations and four margins — that is, where you can see white all the way around the design — can bring hundreds. Mine has four margins, or so I claim. You may need a magnifying glass to discern the thin sliver of white that continues around the lower left of the stamp — but I maintain it is there! Thus I believe my stamp should be worth at least — $70! amps still include “USA,” while Great Britain’s regular issues include nothing but a value and an iconic portrait of Elizabeth II.

amps still include “USA,” while Great Britain’s regular issues include nothing but a value and an iconic portrait of Elizabeth II.

(often from foreign lands), and because they are a little bit pregnant — there is a pleasing heft and lift to the envelopes, a promise of what lies within. Altogether a fairly low-key pleasure, but a pleasure nonetheless. In the the second photo, one envelope is open and the stamps have been removed for a first look (using stamp tongs, of course). It’s always at least a small thrill. Soon enough, the stamps will be safely mounted in their places on the pages of thick stamp albums, and they will take their places in sets from countries around the world — most of which no longer exist. For now, the stamps are out, on the table, colorful

(often from foreign lands), and because they are a little bit pregnant — there is a pleasing heft and lift to the envelopes, a promise of what lies within. Altogether a fairly low-key pleasure, but a pleasure nonetheless. In the the second photo, one envelope is open and the stamps have been removed for a first look (using stamp tongs, of course). It’s always at least a small thrill. Soon enough, the stamps will be safely mounted in their places on the pages of thick stamp albums, and they will take their places in sets from countries around the world — most of which no longer exist. For now, the stamps are out, on the table, colorful  artifacts sometimes well over 100 years old. The stamps have survived all these years. Some are a little faded, others have retained their intense colors, appearing fresh in their third century. This is a time to lift the stamps (in tongs of course), turn them over, examine their backs, look for thins or creases, double-check watermarks. (What are watermarks? Be patient, we’ll get to that.)

artifacts sometimes well over 100 years old. The stamps have survived all these years. Some are a little faded, others have retained their intense colors, appearing fresh in their third century. This is a time to lift the stamps (in tongs of course), turn them over, examine their backs, look for thins or creases, double-check watermarks. (What are watermarks? Be patient, we’ll get to that.) examination and appreciation. (Of course, while you are doing all this, you are also living your life. Please don’t think stamp-collecting is an all-consuming habit. After all, FDR was an active stamp collector all his adult life, and he still had time for other things …)

examination and appreciation. (Of course, while you are doing all this, you are also living your life. Please don’t think stamp-collecting is an all-consuming habit. After all, FDR was an active stamp collector all his adult life, and he still had time for other things …) stated value for mailing purposes. So the senders combine stamps that add up to the going rate — 49 cents in the USA in 2015 (later reduced to 47 cents, a change made even more confusing by the “forever” non-numerical value) — and load up the envelope with the old beauties. Seeing such colorful mail makes the whole thing more fun. I wonder if the letter carrier even gets a tiny kick out of delivering these substantive letter-packets decorated with such philatelic richness.

stated value for mailing purposes. So the senders combine stamps that add up to the going rate — 49 cents in the USA in 2015 (later reduced to 47 cents, a change made even more confusing by the “forever” non-numerical value) — and load up the envelope with the old beauties. Seeing such colorful mail makes the whole thing more fun. I wonder if the letter carrier even gets a tiny kick out of delivering these substantive letter-packets decorated with such philatelic richness. While the U.S. Postal Service no longer issues stamps with denominations for first-class mail (i.e., now you just use “forever” stamps), if you ask at your post office, you will find there are still many different tamps for sale, from 1 cent to $10 and beyond. You just have to ask. The highest-value stamps are for heavier mail, priority mail, express mail and the like. The denominations have progressed upward in recent years — $13.65, $14, $16.50, $18.30 … In 2013, the USPS issued a stamp selling for $19.95 that depicted a

While the U.S. Postal Service no longer issues stamps with denominations for first-class mail (i.e., now you just use “forever” stamps), if you ask at your post office, you will find there are still many different tamps for sale, from 1 cent to $10 and beyond. You just have to ask. The highest-value stamps are for heavier mail, priority mail, express mail and the like. The denominations have progressed upward in recent years — $13.65, $14, $16.50, $18.30 … In 2013, the USPS issued a stamp selling for $19.95 that depicted a  bustling Grand Central Station in New York City; in 2014 came a $19.99 stamp picturing the USS Arizona Memorial. What? You’ve never seen these stamps before? Here is a picture of some of them. They all have been available at one time or another for purchase at most post offices — for face value (i.e., the prince on the stamp). Some of the older stamps that have gone out of circulation, that is, no longer are sold by the post office, have increased in value to collectors. If high-value stamps are a good investment, you’d think some residual value would attach to cancelled examples. And you’d be right. The first Express Mail stamp, issued in 1983 with a price tag of $9.35, sells today for about $40 in mint (uncancelled) condition. But cancelled copies are valuable, too, priced at about $35. The $11.75 Express Mail stamp from the space shuttle series in 1998 sells today for about $30 mint, $19.95 cancelled, or “used.” These are reasons I make a point of collecting used as well as unused copies of these high-value stamps — and ask friends and family to use them so I can collect them right off the packages. To me, the mint and used copies are both worth collecting. And who knows? Some day, these rarely used stamps may be more valuable cancelled than mint!

bustling Grand Central Station in New York City; in 2014 came a $19.99 stamp picturing the USS Arizona Memorial. What? You’ve never seen these stamps before? Here is a picture of some of them. They all have been available at one time or another for purchase at most post offices — for face value (i.e., the prince on the stamp). Some of the older stamps that have gone out of circulation, that is, no longer are sold by the post office, have increased in value to collectors. If high-value stamps are a good investment, you’d think some residual value would attach to cancelled examples. And you’d be right. The first Express Mail stamp, issued in 1983 with a price tag of $9.35, sells today for about $40 in mint (uncancelled) condition. But cancelled copies are valuable, too, priced at about $35. The $11.75 Express Mail stamp from the space shuttle series in 1998 sells today for about $30 mint, $19.95 cancelled, or “used.” These are reasons I make a point of collecting used as well as unused copies of these high-value stamps — and ask friends and family to use them so I can collect them right off the packages. To me, the mint and used copies are both worth collecting. And who knows? Some day, these rarely used stamps may be more valuable cancelled than mint! n a trip to the post office in downtown Moscow. It seemed to me the postal clerks saw her coming and either eyed the exit, rolled their eyes, smiled sympathetically, groaned inwardly, or issued a good-natured sigh. Probably some combination of all of these. It wasn’t always convenient for them to go hunting for high-value stamps. There might be a few other customers waiting in line, also sighing, rolling their eyes, etc. Tolerance for philatelic game-playing is not wide or deep. But Mother generally persevered, alwa

n a trip to the post office in downtown Moscow. It seemed to me the postal clerks saw her coming and either eyed the exit, rolled their eyes, smiled sympathetically, groaned inwardly, or issued a good-natured sigh. Probably some combination of all of these. It wasn’t always convenient for them to go hunting for high-value stamps. There might be a few other customers waiting in line, also sighing, rolling their eyes, etc. Tolerance for philatelic game-playing is not wide or deep. But Mother generally persevered, alwa ys with a kind word and good will. More often than not she prevailed, and the resulting packages had enduring value — not just for the contents, but because of the collectible stamps pasted on them. For example, Mother sent me the $13.65 Express Mail stamp from the monuments series in 2002-3 that you see here. The cancelled copy is catalog-priced at around $9. And to think the stamp already did its duty, carrying Mother’s precious package to me … Now that my old mother is no longer around to run this little philatelic gambit, I have not yet figured out how to get used copies of those $19.95 and $19.99 stamps into my collection through legitimate use of the postal system. I shall keep trying, mercilessly cajoling other loved ones into playing stamps with me …

ys with a kind word and good will. More often than not she prevailed, and the resulting packages had enduring value — not just for the contents, but because of the collectible stamps pasted on them. For example, Mother sent me the $13.65 Express Mail stamp from the monuments series in 2002-3 that you see here. The cancelled copy is catalog-priced at around $9. And to think the stamp already did its duty, carrying Mother’s precious package to me … Now that my old mother is no longer around to run this little philatelic gambit, I have not yet figured out how to get used copies of those $19.95 and $19.99 stamps into my collection through legitimate use of the postal system. I shall keep trying, mercilessly cajoling other loved ones into playing stamps with me … ge and stick the stamp in its space in the album. The hinges are peelable, and will not harm the stamp. For mint (uncancelled) stamps, whose gum needs to be protected, readying the stamp for safe display requires special mounts. Using stamp tongs, insert the stamp in a 10-inch-long protective sleeve — the black strips come in numerous widths to accommodate all sizes of stamps. A 22-strip pack costs less than $10 and can accommodate up 100 stamps. Use a razor cutter to lop off the inserted stamp from the rest of the strip. (But be careful not to nick the stamp, including the perforations!). For this cutting operation, I use a little kit I picked up as a lad in Germany …oh, just about 55 years ago. Amazing, how it’s lasted. We stamp collectors do venerate aged things, after all. On the other hand, how can a durable plastic razor holder and a see-through glass ruler wear out? In cutting, I position the stamp on a piece of cardboard, so I don’t mar my desk top or make an uneven cut. I keep a container of recycled pieces of cardboard nearby for this express purpose. I don’t use pieces of cardboard more than once. Cutting through the strip on top of another cut mark in the cardboard could result in an uneven cut. Even if I am only making one cut for one stamp, I still discard the whole piece of cardboard afterwards. Call it wasteful. Call it extravagance. I prefer to think of it as an infinitesimal act of gay abandon. (The cardboard eventually goes out with the recycling anyway.) Now you are ready to moisten a small part of the back of the black mount — careful not to stick your tongue inside, wet the precious gum and ruin the stamp! — and paste the mounted, protected stamp in its designated spot. Aaah! This is what it’s all about — putting stamps in spaces, seeing sets materialize in all their glorious order and color and design …

ge and stick the stamp in its space in the album. The hinges are peelable, and will not harm the stamp. For mint (uncancelled) stamps, whose gum needs to be protected, readying the stamp for safe display requires special mounts. Using stamp tongs, insert the stamp in a 10-inch-long protective sleeve — the black strips come in numerous widths to accommodate all sizes of stamps. A 22-strip pack costs less than $10 and can accommodate up 100 stamps. Use a razor cutter to lop off the inserted stamp from the rest of the strip. (But be careful not to nick the stamp, including the perforations!). For this cutting operation, I use a little kit I picked up as a lad in Germany …oh, just about 55 years ago. Amazing, how it’s lasted. We stamp collectors do venerate aged things, after all. On the other hand, how can a durable plastic razor holder and a see-through glass ruler wear out? In cutting, I position the stamp on a piece of cardboard, so I don’t mar my desk top or make an uneven cut. I keep a container of recycled pieces of cardboard nearby for this express purpose. I don’t use pieces of cardboard more than once. Cutting through the strip on top of another cut mark in the cardboard could result in an uneven cut. Even if I am only making one cut for one stamp, I still discard the whole piece of cardboard afterwards. Call it wasteful. Call it extravagance. I prefer to think of it as an infinitesimal act of gay abandon. (The cardboard eventually goes out with the recycling anyway.) Now you are ready to moisten a small part of the back of the black mount — careful not to stick your tongue inside, wet the precious gum and ruin the stamp! — and paste the mounted, protected stamp in its designated spot. Aaah! This is what it’s all about — putting stamps in spaces, seeing sets materialize in all their glorious order and color and design …

stamps (see photo, top right). But there seems to be a design error: The president’s right hand holds a magnifying glass and is just fine; however, he clasps a stamp in a left hand that contains five fingers — and a thumb! (You’d think this stamp would be valuable, but you can buy it for a quarter.) One further note on this bit of arcana — the photograph the engraver used actually does seem to show “six finger

stamps (see photo, top right). But there seems to be a design error: The president’s right hand holds a magnifying glass and is just fine; however, he clasps a stamp in a left hand that contains five fingers — and a thumb! (You’d think this stamp would be valuable, but you can buy it for a quarter.) One further note on this bit of arcana — the photograph the engraver used actually does seem to show “six finger s,” though closer perusal reveals the extra “pinkie” as distorted image of FDR’s shirt cuff. It must be!

s,” though closer perusal reveals the extra “pinkie” as distorted image of FDR’s shirt cuff. It must be! , James A. Farley (seen here in a very flattering formal oil portrait), was an old friend and mentor in

, James A. Farley (seen here in a very flattering formal oil portrait), was an old friend and mentor in

the sheets, and

the sheets, and How to collect these items? None of the stamps are particularly valuable by themselves. (The original national parks set of 10 sells online for well under $10.) Should you try and get a full sheet, unperforated and ungummed, as an unusual but somewhat spurious collector’s item? What about all the other souvenir sheets, vertical and horizontal “gutter pairs,” “arrow” blocks of six and other Farley shenanigans? Cut out from their sheets or other special settings, aren’t the stamps the same? And get a load of this odd note, from the fine print of my Scott catalogue: “In 1940, the P.O. Department offered to and did gum full sheets of Nos. 754 to 771 sent in by owners” — thus creating new philatelic varieties, it would seem.

How to collect these items? None of the stamps are particularly valuable by themselves. (The original national parks set of 10 sells online for well under $10.) Should you try and get a full sheet, unperforated and ungummed, as an unusual but somewhat spurious collector’s item? What about all the other souvenir sheets, vertical and horizontal “gutter pairs,” “arrow” blocks of six and other Farley shenanigans? Cut out from their sheets or other special settings, aren’t the stamps the same? And get a load of this odd note, from the fine print of my Scott catalogue: “In 1940, the P.O. Department offered to and did gum full sheets of Nos. 754 to 771 sent in by owners” — thus creating new philatelic varieties, it would seem. to erase the stereotype of the geeky stamp collector, dusty, bespectacled, aging, beetling about his business (like me). I have little confidence left in the tradition of fathers passing along their interest in stamps to sons — as my father somehow did with me. As far as I can tell, my older brother Jonathan and I are the only ones in my extended, intergenerational family circle who give a hoot about stamps. Too bad, because stamps are worth paying attention to.

to erase the stereotype of the geeky stamp collector, dusty, bespectacled, aging, beetling about his business (like me). I have little confidence left in the tradition of fathers passing along their interest in stamps to sons — as my father somehow did with me. As far as I can tell, my older brother Jonathan and I are the only ones in my extended, intergenerational family circle who give a hoot about stamps. Too bad, because stamps are worth paying attention to.

shot of

shot of

Britain’s Queen Elizabeth was a real enabler of Sarkozy, handing him one philatelic trophy after another. To be sure, she had plenty to give — the queen was heir to a stunning collection begun by her grandfather, and expanded by her father.

Britain’s Queen Elizabeth was a real enabler of Sarkozy, handing him one philatelic trophy after another. To be sure, she had plenty to give — the queen was heir to a stunning collection begun by her grandfather, and expanded by her father. George V’s original collection filled 328 60-page red albums; his son George VI’s albums are blue; Elizabeth’s are green. It seems George V got started long before he became king, aided by Prince Alfred, his uncle and Duke of Edinburgh. The king’s philatelic ambitions soared. He once wrote an adviser, “I wish to have the best & not one of the best collections in England.” He certainly tried to achieve his goal. In addition to accumulating special items by dint of his royal access, the king made astute purchases, acquiring such rarities as the Post Office Mauritius and the Great Britain Two Pence Tyrian Plum. (Don’t you just love the name of that color?)

George V’s original collection filled 328 60-page red albums; his son George VI’s albums are blue; Elizabeth’s are green. It seems George V got started long before he became king, aided by Prince Alfred, his uncle and Duke of Edinburgh. The king’s philatelic ambitions soared. He once wrote an adviser, “I wish to have the best & not one of the best collections in England.” He certainly tried to achieve his goal. In addition to accumulating special items by dint of his royal access, the king made astute purchases, acquiring such rarities as the Post Office Mauritius and the Great Britain Two Pence Tyrian Plum. (Don’t you just love the name of that color?) raightforward monarch, quite popular during his reign and well-suited to his times — though it’s hard to see how collecting all those stamps bearing his profile could not have swelled his royal head. He is credited with helping to revive a hobby that had grown a bit moribund. (Where is the next George when we need him?!) A popular story has one of his retainers reporting that “Some damned fool had paid as much as L1,400 (about $3,600) for one stamp,” and the king mildly replying, “Yes, I was that damned fool.” His investment paid off: The rarity in question later sold at auction for $3.9 million.

raightforward monarch, quite popular during his reign and well-suited to his times — though it’s hard to see how collecting all those stamps bearing his profile could not have swelled his royal head. He is credited with helping to revive a hobby that had grown a bit moribund. (Where is the next George when we need him?!) A popular story has one of his retainers reporting that “Some damned fool had paid as much as L1,400 (about $3,600) for one stamp,” and the king mildly replying, “Yes, I was that damned fool.” His investment paid off: The rarity in question later sold at auction for $3.9 million.

** In addition to collecting stamps, little Freddy began a daily diary in Dacca, when he was eight, and kept it up until high school and sporadically, beyond. When I get around to reviewing its generally hum-drum contents in coming years, no doubt I will find specifics about the years-long set-to with the Kenmore Stamp Company. Accordingly, I shall endeavor to keep this record updated with my findings.

** In addition to collecting stamps, little Freddy began a daily diary in Dacca, when he was eight, and kept it up until high school and sporadically, beyond. When I get around to reviewing its generally hum-drum contents in coming years, no doubt I will find specifics about the years-long set-to with the Kenmore Stamp Company. Accordingly, I shall endeavor to keep this record updated with my findings. ar newspaper career in 2013. He has degrees from Harvard and Columbia, and was president of the National Conference of Editorial Writers in 2001. He lives in retirement near Syracuse, NY.

ar newspaper career in 2013. He has degrees from Harvard and Columbia, and was president of the National Conference of Editorial Writers in 2001. He lives in retirement near Syracuse, NY.