Before we get to the siege of Mafeking, which is quite a yarn, I must present some preliminary information. Our story picks up long before the siege in 1899. Back in the 1880s, the Cape Colony asserted its prerogatives over mineral-rich Griqualand West, a Boer stronghold, and in addition Stellaland, a Boer “republic” created for the sole purpose of forestalling British ambitions, as far as I can tell.

This was happening as diamonds, gold and other resources were being discovered in nearby Kimberly and environs. The land of the Griquas was smack in the center of things. The mining rush that ensued, engulfed the areas known as Griqualand East and the considerably larger Griqualand West, with Boer and Brit interests clashing, often violently, until the eventual outcome — more an entente between white supremacists than a true reckoning.

In any case, both Griqualand West and Stellaland, which only was in business for  about a year, issued stamps. In the case of Griqualand, the stamps were simply Cape of Good Hope rectangles overprinted “G” in myriad ways. (See illustrations here from my collection). Stamp collectors beware: collecting all 102 Griqualand overprints could get expensive.

about a year, issued stamps. In the case of Griqualand, the stamps were simply Cape of Good Hope rectangles overprinted “G” in myriad ways. (See illustrations here from my collection). Stamp collectors beware: collecting all 102 Griqualand overprints could get expensive.

In the case of Stellaland, a set was issued under Boer authority displaying a coat of arms like a “real country.” Just one set — three stamps — but there you have it. And the stamps aren’t cheap. (I paid

$25 for these three in 2005.)

The fortunes of the Boers and the Brits rose and fell from the 1870s on, culminating in the brutal Second Boer War of 1899-1902. Early on, the Cape Colony usurped the Boers in Stellaland and took over in the mid-1880s — but not before there occurred an odd philatelic pas de deux. Check out the two so-called “Vryburg” stamps presented at right, named for the capital city of Stellaland. One stamp is a replica of  an extremely rare Boer stamp overprinted “V.R.: (Victoria Regina) for the British occupiers. The other is a Cape Colony rectangle overprinted “Z.A.R.” for the Boer occupiers (Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek). And wow! Check out the price. What we have here, then, is both European forces asserting their

an extremely rare Boer stamp overprinted “V.R.: (Victoria Regina) for the British occupiers. The other is a Cape Colony rectangle overprinted “Z.A.R.” for the Boer occupiers (Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek). And wow! Check out the price. What we have here, then, is both European forces asserting their  primacy by cancelling the stamp y of their enemy with the overprint of their own] side. Who was really in charge here? Did it matter as far as the local black population was concerned? It certainly mattered as far as it resulted in black lives lost during the fighting between the white “tribes” — the Boers and the Brits!

primacy by cancelling the stamp y of their enemy with the overprint of their own] side. Who was really in charge here? Did it matter as far as the local black population was concerned? It certainly mattered as far as it resulted in black lives lost during the fighting between the white “tribes” — the Boers and the Brits!

By the way, if you think this is confusing, wait until we take up the subject of Tansvaal/Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek. There we face alternating Boer and British authority, as well as local overprints and who-know-what-else. Ah well, that is for another day …

Now take a look at this stamp (right). It is quite extraordinary. The overprint “Mafeking Besieged” on the Cape of Good Hope half-penny stamp identifies the desperate straits faced by the inhabitants of the Cape Colony’s inland city and strategic railway town. Stamps with this Mafeking overprint sell for a premium — I bought this average-quality one for L19.25. Other Mafeking stamps are much more valuable. My example has a somewhat rounded corner, upper left. But really, considering what a rarity it is, I’d expect you to be on my side on this.

Now take a look at this stamp (right). It is quite extraordinary. The overprint “Mafeking Besieged” on the Cape of Good Hope half-penny stamp identifies the desperate straits faced by the inhabitants of the Cape Colony’s inland city and strategic railway town. Stamps with this Mafeking overprint sell for a premium — I bought this average-quality one for L19.25. Other Mafeking stamps are much more valuable. My example has a somewhat rounded corner, upper left. But really, considering what a rarity it is, I’d expect you to be on my side on this.

When I showed this stamp to my Syracuse Stamp Club buddies, one of them came up with an obvious, if incisive, question: If British Mafeking was indeed besieged by the Boers, how come there is this cancelled stamp, indicating that the mail got through? If it was a siege, how could letters reach their destinations?

I hadn’t confronted this obvious question before, but it led to further inquiry into the Mafeking siege — in particular the heroic eccentricities of British scion Col. Robert Baden-Powell. Much of the following account is drawn from Wikipedia, and is well-sourced. There is no good reason to doubt the authenticity of this narrative. If anything, it may be overly Eurocentric, that is, glossing over the multi-racial nature of the campaign.

First, though, an editorial comment — a prologue to the dramatic tale of the Siege of Mafeking. This story could should be made into a movie — there are many cinematic episodes in a compact narrative crammed into a mere seven months. The backdrop is the standoff between the Brits and the Boers, between Col. Baden-Powell and Gen. Piet Cronje. The screenplay could be constructed as drama, tragedy or farce. As farce, you might cast John Cleese — at least a young, supple version of him — as the languidly energetic and boyishly resourceful Baden-Powell. Gen. Cronje might be Cpl. Klink from the TV show “Hogan’s Heroes.” Then you’d enlist a veritable Monty Python cast to concoct and carry out the various pranks and tricks Baden-Powell pulled off to hoodwink the stolid Boers, who might as well be Keystone Kops in their dim-witted and ineffectual rage.

Here is one of the two locally produced Mafeking stamps. the image is from the internet — I couldn’t afford the hundreds of dollars it would cost to buy either one. (Plus, the catalogue warns, there are “excellent forgeries.”) It seems the plucky designers used a photographic technique in reproducing the image of Col Baden-Powell — though his collar makes him look decapitated! The banner on top reads, ”Mafeking Siege 1900” — an oddly celebratory touch. To be sure, Col B.-P. put a lot of emphasis on maintaining morale, and may have encouraged his troops to keep these stamps as souvenirs. I wouldn’t be surprised to learn he was a stamp-fancier himself.

The siege of Mafeking may have had its farcical qualities, and the actual number of deaths was not large. However, the Boer War — actually there were two wars, about 10 years apart — was no picnic. Casualty estimates later put the total number of dead at 22,000 on the British side, 25,000 on the Boer side. At least 350 British soldiers perished in the Battle of Spion Kop alone (the Boers suffered 300 casualties), and 7,000 Brits were killed or wounded during the relief of Ladysmith, a city in Natal besieged by the Boers. Many of the Boer dead were women and children penned up by the British as prisoners in the deplorable conditions of new “concentration camps.” The Brits’ scorched-earth policies, and their appalling treatment of prisoners, helped bring about the Geneva Conventions, ratified in 1904.

The siege of Mafeking began Oct. 13, 1899, with a shelling by the Boers. It ended May 17, 1900, with the arrival of British reinforcements — including Baden-Powell’s brother, Baden Fletcher Smyth Baden-Powell (played by Hugh Grant in the movie, I suggest.) Though initially outnumbered four-to-one, the plucky British held out for 217 days.

Here are a few cinematic examples of Baden-Powell’s schemes;

*** He devised a series of interlocking trenches to allow his troops to circulate without being seen.

*** He had his men conspicuously place “mines” around the perimeter, all of which were fakes.

*** Troops went to elaborate lengths to mimic avoiding (imaginary) barbed wire while moving about.

*** Col. B.-P. transferred his limited supply of guns from one place to another so Boer spies would overestimate his arsenal.

*** Using an acetylene lamp and a biscuit tin, he concocted a search light that would be displayed in multiple locations to suggest numerous beacon emplacements.

*** He noticed that while the Boers had cut telephone lines and stopped the trains, they had not damaged the tracks; so he commandeered an armored train from Mafeking’s rail yards, loaded it with sharpshooters and sent it careening into the heart of the Boer camp — and back safely.

*** A makeshift howitzer was built in the Mafeking rail workshops; rail workers also repurposed a century-old cannon.

*** Troops cross-dressed as women when doing chores or moving about the camp to increase enemy confusion.

Day after day, week after week, Baden-Powell and his stalwarts taunted and defied the Boers. One after another, the hijinks and stunts of the British confounded the would-be attackers. A final Boer assault in May was thwarted by Baden-Powell’s strategic counterattack. The toll in that encounter was 12 dead, eight wounded on the British side, most of them blacks; the Boer toll was 60 dead or wounded and 108 captured. Days later, the Boers threw up their hands and went home. (British reinforcements were arriving anyway.)

Two days after the siege was lifted, an American agent reported to The Times: “Baden-Powell is a wonderfully able scout and quick at sketches. I do not know another who could have done the work at Mafeking if the same conditions had been imposed. All the bits of knowledge he studiously gathered have been utilized in saving that community.”

This popular stamp was the other local issue, known as the “1d Cadet Sgt-Major Goodyear ‘Bicycle’ “ stamp. How to break that down, I don’t quite know. The stamp reportedly portrays a native Cadet cyclist, aged 12, who was among the boys carrying letters and news across enemy lines. If you examine the design closely, you will notice that the bicyclist is black.

Yes, there was drama in the derring-do of the besieged in Mafeking — including the young black cyclists and runners who crossed through enemy lines to carry the mail from Mafeking, complete with duly cancelled stamps overprinted “Mafeking Besieged.” Eventually there was a pair of locally designed and produced postage stamps. The drama continued after the siege of Mafeking was relieved and news reached Mother England, to great jubilation. A new verb was coined, “to maffick,” meaning to celebrate extravagantly. The home country made a great fuss over Baden-Powell: there were parades, honors, etc. etc. He was named the Army’s youngest major general, then ennobled. Lord B.-P went on to found the Boy Scouts — mindful of those scrappy African boys who risked their lives doing their duty.

And yes, there was tragedy in the siege of Mafeking. It was supposed to be a battle between whites — Boers and Brits — so why were so many of the casualties blacks? The majority of fighters on the British side were white, but Baden-Powell recruited hundreds of blacks to guard the city’s perimeter. No matter which side won the siege, or the larger Boer War itself, black Africans had little to gain. The dream of multi-racial self-government, envisioned by Prime Minister John Molteno in the Cape Colony 20 years earlier, was fading. The racist policies of the Boers and the British Crown were on the ascendant. While Britain may have subdued the Boers, the outcome ensured that the future of South Africa would be built on white supremacy, not equal rights.

TO BE CONTINUED

Behold! The Cape of Good Hope. Or should we use the name of the Portuguese who first rounded the point in the late 1400s, which they dubbed Cabo da Boa Esperanca? ….

Behold! The Cape of Good Hope. Or should we use the name of the Portuguese who first rounded the point in the late 1400s, which they dubbed Cabo da Boa Esperanca? …. to found Cape Town (about 25 miles north of the cape on the map).

to found Cape Town (about 25 miles north of the cape on the map). Here is an ancient map of the Cape of Good Hope, during a time when the Dutch and the Afrikaners and the Boers and the English lived as uneasy neighbors with each other — and the Xhosa and the Zulu. No one could have imagined what heartbreak and outrage would result from the transformational European incursion, starting at the Cape of Good Hope and spreading across southern Africa.

Here is an ancient map of the Cape of Good Hope, during a time when the Dutch and the Afrikaners and the Boers and the English lived as uneasy neighbors with each other — and the Xhosa and the Zulu. No one could have imagined what heartbreak and outrage would result from the transformational European incursion, starting at the Cape of Good Hope and spreading across southern Africa.  Above is my example of the first stamp issued for the Cape of Good Hope: No. 1, on bluish paper. It came out in 1853, just six years after the first U.S. stamp. The somewhat crude but elegant engraving depicts a seated figure — “Hope” — with an anchor as an appropriate nautical emblem. Hope’s image would grace COGH stamps for the rest of the century. The triangular shape must have been a sensation at the time; and imagine! For a British territory at the southern tip of Africa! How exotic. The shape of the stamp itself suggests a geographical cape, don’t you think?

Above is my example of the first stamp issued for the Cape of Good Hope: No. 1, on bluish paper. It came out in 1853, just six years after the first U.S. stamp. The somewhat crude but elegant engraving depicts a seated figure — “Hope” — with an anchor as an appropriate nautical emblem. Hope’s image would grace COGH stamps for the rest of the century. The triangular shape must have been a sensation at the time; and imagine! For a British territory at the southern tip of Africa! How exotic. The shape of the stamp itself suggests a geographical cape, don’t you think? I also got these two (left and below left) from my father. The 4d above, also from 1853,

I also got these two (left and below left) from my father. The 4d above, also from 1853, considerably off-center beat-up image. My Minkus album offers this notation: “Fine lines of background blurred or broken; printing less clear due to wear of plates …” This stamp is valued at $45, but mine is not a particularly well-cut example.

considerably off-center beat-up image. My Minkus album offers this notation: “Fine lines of background blurred or broken; printing less clear due to wear of plates …” This stamp is valued at $45, but mine is not a particularly well-cut example. Above are two examples from the first set of the “Hope” rectangles. If you look closely at the outside border of each of these two stamps, you will notice that there is a thin frame line that extends around the entire stamp. This is the only set that would have frame lines around the outside. What explains this change in later issues? Take a look at the stamps below, and you may decide, like me, that it’s probably a wise design decision — to eliminate the frame around the entire stamp; it’s slightly simpler, more coherent and elegant.

Above are two examples from the first set of the “Hope” rectangles. If you look closely at the outside border of each of these two stamps, you will notice that there is a thin frame line that extends around the entire stamp. This is the only set that would have frame lines around the outside. What explains this change in later issues? Take a look at the stamps below, and you may decide, like me, that it’s probably a wise design decision — to eliminate the frame around the entire stamp; it’s slightly simpler, more coherent and elegant. Well before the first “Cape of Good Hope” set was issued, the British territory had expanded far beyond the cape itself. The map at left is from the early 1800s, and shows clearly how “civilization” is spreading east and north from the cape.

Well before the first “Cape of Good Hope” set was issued, the British territory had expanded far beyond the cape itself. The map at left is from the early 1800s, and shows clearly how “civilization” is spreading east and north from the cape. By the time this map appeared after mid-century, the burgeoning Cape Colony was beginning to look like a map of New Jersey with its intricate territorial divisions.

By the time this map appeared after mid-century, the burgeoning Cape Colony was beginning to look like a map of New Jersey with its intricate territorial divisions. After 1872, the Cape Colony had the same rights within the British imperial system as Canada and Australia. It still issued stamps with the name “Cape of Good Hope,” but it was about to become the biggest baddest colony in Africa.

After 1872, the Cape Colony had the same rights within the British imperial system as Canada and Australia. It still issued stamps with the name “Cape of Good Hope,” but it was about to become the biggest baddest colony in Africa. Here is a map of Cape Colony at its apex, in 1898. In the 1904 census, the population of the Cape Colony was 2.4 million. That included 1.4 million blacks and almost 580,000 whites. The land mass covered 219,700 square miles — four times the size of the UK — yet the stamps still bore the name, “Cape of Good Hope.” Go figure. (You can still see the COGH sticking out like an inverted thumb-down near Africa’s southwestern tip.)

Here is a map of Cape Colony at its apex, in 1898. In the 1904 census, the population of the Cape Colony was 2.4 million. That included 1.4 million blacks and almost 580,000 whites. The land mass covered 219,700 square miles — four times the size of the UK — yet the stamps still bore the name, “Cape of Good Hope.” Go figure. (You can still see the COGH sticking out like an inverted thumb-down near Africa’s southwestern tip.) Before we go any further, let me share what I’ve learned about how well the Cape Colony was governed in its early years. From the start there was lots of restless energy among the motivated groups of Dutch and English settlers, and considerable curiosity among the indigenous Xhosa, Zulu and other Bantu peoples. As the English, Boers and Afrikaners migrated along the coast and into the interior, they confronted each other and the native population with varying degrees of tolerance and respect. The Boers of the Orange Free State and Central African Republic established a racist hierarchy that subjugated the black African populations that surrounded and outnumbered them. The British, too, favored a racist hierarchy in Natal, Transvaal and the Cape Colony.

Before we go any further, let me share what I’ve learned about how well the Cape Colony was governed in its early years. From the start there was lots of restless energy among the motivated groups of Dutch and English settlers, and considerable curiosity among the indigenous Xhosa, Zulu and other Bantu peoples. As the English, Boers and Afrikaners migrated along the coast and into the interior, they confronted each other and the native population with varying degrees of tolerance and respect. The Boers of the Orange Free State and Central African Republic established a racist hierarchy that subjugated the black African populations that surrounded and outnumbered them. The British, too, favored a racist hierarchy in Natal, Transvaal and the Cape Colony. John Molteno (right) was born in 1814 in London, part of a large English-Italian family of modest means. He shipped out to the Cape Colony as a teenager, working as a library assistant. He rose rapidly through the ranks because of his keen intelligence, outgoing manner and manifest competence. He won support from the Boers early on when he joined them in the Xhosa wars. Unlike the Boers, he espoused a lifelong commitment to equal rights for whites and blacks. When the British pressed for consolidation with the racist Boer republics in southern Africa in 1878, Molteno objected, on the grounds that the Boers would not tolerate the Cape Colony’s universal franchise. He lost his fight, and he was right. Molteno married three times. His first wife was “coloured” and died in childbirth. He went on to have 19 children; among his many descendants were anti-apartheid activists.

John Molteno (right) was born in 1814 in London, part of a large English-Italian family of modest means. He shipped out to the Cape Colony as a teenager, working as a library assistant. He rose rapidly through the ranks because of his keen intelligence, outgoing manner and manifest competence. He won support from the Boers early on when he joined them in the Xhosa wars. Unlike the Boers, he espoused a lifelong commitment to equal rights for whites and blacks. When the British pressed for consolidation with the racist Boer republics in southern Africa in 1878, Molteno objected, on the grounds that the Boers would not tolerate the Cape Colony’s universal franchise. He lost his fight, and he was right. Molteno married three times. His first wife was “coloured” and died in childbirth. He went on to have 19 children; among his many descendants were anti-apartheid activists. Molteno’s two key associates were John X. Merriman and Saul Solomon. Merriman’s extraordinary gift for administration helped build the Cape Colony into the economic engine that would power South Africa. Molteno persuaded Merriman of the importance of equal rights. At the end of the century, as the racist policies of Boer leader Paul Kruger became more dominant, Merriman presciently warned: “The greatest danger to the future lies in the attitude of President Kruger, and his vain hope of building up a state in a narrow, unenlightened minority.”

Molteno’s two key associates were John X. Merriman and Saul Solomon. Merriman’s extraordinary gift for administration helped build the Cape Colony into the economic engine that would power South Africa. Molteno persuaded Merriman of the importance of equal rights. At the end of the century, as the racist policies of Boer leader Paul Kruger became more dominant, Merriman presciently warned: “The greatest danger to the future lies in the attitude of President Kruger, and his vain hope of building up a state in a narrow, unenlightened minority.”

Above is the last set issued by the Cape Colony, starting in 1902 with the death of Queen Victoria and the start of the relatively short reign of her aging son, Edward VII. There’s nothing special about the set, except that I want to show it off because I have it complete, from the 1/2d to the 5 shilling. You may find the set online for under $20.

Above is the last set issued by the Cape Colony, starting in 1902 with the death of Queen Victoria and the start of the relatively short reign of her aging son, Edward VII. There’s nothing special about the set, except that I want to show it off because I have it complete, from the 1/2d to the 5 shilling. You may find the set online for under $20. To the right is the first stamp of the Union of South Africa in 1910, the same year as the death of Edward VII and the ascent of his son, George V, to the throne. The union comprised the Cape Colony, Orange Free State, Transvaal and Natal (see coats of arms in the corners). As you can see from the map below, the union encompassed the whole of southern Africa with the exception of Swaziland and Basutoland.

To the right is the first stamp of the Union of South Africa in 1910, the same year as the death of Edward VII and the ascent of his son, George V, to the throne. The union comprised the Cape Colony, Orange Free State, Transvaal and Natal (see coats of arms in the corners). As you can see from the map below, the union encompassed the whole of southern Africa with the exception of Swaziland and Basutoland.

In 1961, the Union of South Africa became the Republic of South Africa (RSA). This name change did not alter the repugnant system of apartheid or improve the lives of black South Africans in any significant way. The RSA would not abandon apartheid until the 1990s.

In 1961, the Union of South Africa became the Republic of South Africa (RSA). This name change did not alter the repugnant system of apartheid or improve the lives of black South Africans in any significant way. The RSA would not abandon apartheid until the 1990s.

To start off, look at these two dandy examples of the first “rectangle” set (right). Notice the frame going all the way around the outside of each stamp. Do you see it? Do you? Do you? Look hard! See it? (Here’s a helpful note from The New World-Wide Postage Stamp Catalogue: “Worn plates of 1p, 4p show no top or outer frame lines.” I can hardly see them here either.)

To start off, look at these two dandy examples of the first “rectangle” set (right). Notice the frame going all the way around the outside of each stamp. Do you see it? Do you? Do you? Look hard! See it? (Here’s a helpful note from The New World-Wide Postage Stamp Catalogue: “Worn plates of 1p, 4p show no top or outer frame lines.” I can hardly see them here either.) Now as a contrast, look at this pair (right). See the frame stop at the upper and lower border of the image? You might or might not be interested to know why one of these 3d stamps cost me $7.75 and the other didn’t. The reason is that the expensive one is listed in the catalogue as No. 25, ‘lilac rose (’80),” while the one on the right is listed as No. 26, “claret (’81)”

Now as a contrast, look at this pair (right). See the frame stop at the upper and lower border of the image? You might or might not be interested to know why one of these 3d stamps cost me $7.75 and the other didn’t. The reason is that the expensive one is listed in the catalogue as No. 25, ‘lilac rose (’80),” while the one on the right is listed as No. 26, “claret (’81)” This stamp is not distinguished or valuable, but I include it because it is the only mint (uncancelled) variety I have from these Cape of Good Hope sets. I puzzled for some time over what are described as “emblems of the colony.” What at first looks like a wheel is the anchor, of course. That’s a ram standing inside the anchor’s curved heel, right? In the background are grapes, I’ll bet. And Hope is leaning on … well, that took me more time to figure out. Is it a lute or some other stringed instrument? Something to press grapes into wine? Something to poke or slaughter a ram with? Is she holding something, like a mug or flagon? Is she drunk on grape wine?

This stamp is not distinguished or valuable, but I include it because it is the only mint (uncancelled) variety I have from these Cape of Good Hope sets. I puzzled for some time over what are described as “emblems of the colony.” What at first looks like a wheel is the anchor, of course. That’s a ram standing inside the anchor’s curved heel, right? In the background are grapes, I’ll bet. And Hope is leaning on … well, that took me more time to figure out. Is it a lute or some other stringed instrument? Something to press grapes into wine? Something to poke or slaughter a ram with? Is she holding something, like a mug or flagon? Is she drunk on grape wine? Here’s one that got away. The image is from online. It’s a half-decent example of No. 5, the 1 shilling yellow green (yellow green?). It catalogues at $175, and is a pretty example. I could have bought it for $35, but I let it slip away. (Sigh …)

Here’s one that got away. The image is from online. It’s a half-decent example of No. 5, the 1 shilling yellow green (yellow green?). It catalogues at $175, and is a pretty example. I could have bought it for $35, but I let it slip away. (Sigh …)

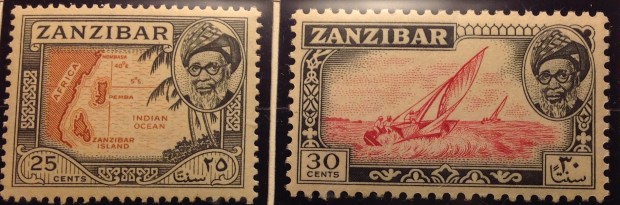

built, the port was developed, sanitation and living standards improved. It’s not as though the people had anything to say about it, though. The British overlords deserve at least as much credit as the sultan for any

built, the port was developed, sanitation and living standards improved. It’s not as though the people had anything to say about it, though. The British overlords deserve at least as much credit as the sultan for any

The sultans and their British masters had been in cahoots for more than a century, lording it over the people. It’s sadly predictable that a month after Zanzibar gained its independence (“uhuru”) in December, 1963, a bloody insurrection overthrew Sultan Jamshid bin Abdullah (pictured at left). The last sultan was able to escape into exile. At this writing, he is 90 years old and living in Portsmouth, England, where he settled with his wife and seven children.

The sultans and their British masters had been in cahoots for more than a century, lording it over the people. It’s sadly predictable that a month after Zanzibar gained its independence (“uhuru”) in December, 1963, a bloody insurrection overthrew Sultan Jamshid bin Abdullah (pictured at left). The last sultan was able to escape into exile. At this writing, he is 90 years old and living in Portsmouth, England, where he settled with his wife and seven children. last sultan, Jamshid, didn’t have time to put out an updated definitive set using his own portrait. The

last sultan, Jamshid, didn’t have time to put out an updated definitive set using his own portrait. The  stamp at right is a record of unfolding history — “uhuru” in 1963 and “jamhuri” in 1964. How Is a republic an improvement over a constitutional monarchy? Discuss.

stamp at right is a record of unfolding history — “uhuru” in 1963 and “jamhuri” in 1964. How Is a republic an improvement over a constitutional monarchy? Discuss.

Later in 1965, revolutionary postal officials finally acknowledged Zanzibar’s official merger with Tanzania, though they brashly stuck their islands’ name ahead of the mainland in the ungainly title

Later in 1965, revolutionary postal officials finally acknowledged Zanzibar’s official merger with Tanzania, though they brashly stuck their islands’ name ahead of the mainland in the ungainly title  At right is a stamp from a short set of 1966, celebrating the second anniversary of the Zanzibar Revolution. Notice the rifle. Notice at the bottom of the stamp is the name “Zanzibar Tanzania.” Is Tanzania implicated in the Zanzibar Revolution, or what? Would the merger have happened without the revolution? Discuss.

At right is a stamp from a short set of 1966, celebrating the second anniversary of the Zanzibar Revolution. Notice the rifle. Notice at the bottom of the stamp is the name “Zanzibar Tanzania.” Is Tanzania implicated in the Zanzibar Revolution, or what? Would the merger have happened without the revolution? Discuss.

**Note:

**Note:

Here is an example of why stamp collectors get a reputation for being kind of … kooky. Look at this envelope (right). The colored labels are postage-due stamps from 1931, carrying nothing more than the value and the message, “Insufficiently prepaid postage due.” They don’t even say “Zanzibar.’ The cover is selling online for $3,674. OK, it’s rare. But hardly in demand. And they sure aren’t very pretty.

Here is an example of why stamp collectors get a reputation for being kind of … kooky. Look at this envelope (right). The colored labels are postage-due stamps from 1931, carrying nothing more than the value and the message, “Insufficiently prepaid postage due.” They don’t even say “Zanzibar.’ The cover is selling online for $3,674. OK, it’s rare. But hardly in demand. And they sure aren’t very pretty. How to summarize the 50-plus years of Zanzibar history after 1964? I’ll just say a few words. The stamp at left shows an inverted “Jamhuri” hand overprint from 1964. Looks like someone acted carelessly, perhaps in haste. You can buy these inverts online for $10 and up. The errors seem fitting, considering the upside-down story

How to summarize the 50-plus years of Zanzibar history after 1964? I’ll just say a few words. The stamp at left shows an inverted “Jamhuri” hand overprint from 1964. Looks like someone acted carelessly, perhaps in haste. You can buy these inverts online for $10 and up. The errors seem fitting, considering the upside-down story

I had intended to get on with the south-central-east Africa postal history overview, but suddenly I have been distracted by … la belle France. I promise to get back straightaway to the Africa overview. Indeed, I have a delectable presentation on Zanzibar all ready to go. Might as well start with the “Z”s, right?

I had intended to get on with the south-central-east Africa postal history overview, but suddenly I have been distracted by … la belle France. I promise to get back straightaway to the Africa overview. Indeed, I have a delectable presentation on Zanzibar all ready to go. Might as well start with the “Z”s, right? auction with those already in my stock book. (see right and below) The result was a pleasing display of many values in myriad hues, all bearing the classic design of “la France feminine” —

auction with those already in my stock book. (see right and below) The result was a pleasing display of many values in myriad hues, all bearing the classic design of “la France feminine” —  Peace bearing an olive branch. Good luck with that in the 1930s …

Peace bearing an olive branch. Good luck with that in the 1930s … There is at least one other area I would like to explore sometime, involving French stamps. It’s about those wonderful landscape engravings that France has been issuing since the 1930s. The artists and engravers

There is at least one other area I would like to explore sometime, involving French stamps. It’s about those wonderful landscape engravings that France has been issuing since the 1930s. The artists and engravers  behind these small masterpieces of line, color and composition deserve attention, and no doubt there are stories to tell …

behind these small masterpieces of line, color and composition deserve attention, and no doubt there are stories to tell … buying at the local post office. Indeed, I remember visiting Notre Dame du Haut, the church designed by Le Corbusier in Ronchamp, and buying the stamp, with the splendid engraving of the church,

buying at the local post office. Indeed, I remember visiting Notre Dame du Haut, the church designed by Le Corbusier in Ronchamp, and buying the stamp, with the splendid engraving of the church, DIARY EXCERPT:

DIARY EXCERPT:  Blois and saw chateau. Got to Tours at 4. Walked around and saw cathedral til 6. Then went to the Blairs’ house for supper. Was great fun, cause there were so many there. Bed 12. …

Blois and saw chateau. Got to Tours at 4. Walked around and saw cathedral til 6. Then went to the Blairs’ house for supper. Was great fun, cause there were so many there. Bed 12. …

All three times we visited France,

All three times we visited France, Oleron had it all — wild waves for body surfing at Vertbois (la cote sauvage), shopping in St. Denis, St. Pierre

Oleron had it all — wild waves for body surfing at Vertbois (la cote sauvage), shopping in St. Denis, St. Pierre DIARY EXCERPTS:

DIARY EXCERPTS:  1960s, I managed to discover

1960s, I managed to discover

This set, which started in 1900, depicts various feminine allegories — for liberty, equality, fraternity the rights of man, more liberty, and peace. I have included a number of color varieties, which are noticeable. Note also the subtle bi-color designs on the higher-value, wider rectangles. A couple of them are a bit rare.

This set, which started in 1900, depicts various feminine allegories — for liberty, equality, fraternity the rights of man, more liberty, and peace. I have included a number of color varieties, which are noticeable. Note also the subtle bi-color designs on the higher-value, wider rectangles. A couple of them are a bit rare.  La semeuse, the sower, is the female allegory in this early design. The set started coming out in 1903, with new values released up to 1938. This classic design coexisted with another long set — of roughly the same design — which you will find

La semeuse, the sower, is the female allegory in this early design. The set started coming out in 1903, with new values released up to 1938. This classic design coexisted with another long set — of roughly the same design — which you will find  on the next page. Why the two sets with the same design? Je ne sais pas, monsieurs-dames! I only ask that you agree with me that this allegory is an altogether pleasing figure. It is modeled after a medallion designed by Oscar Roty for the Department of Agriculture in the 1880s. The image appeared on French coins until 2001. An old Stampex pamphlet provides this “La Boheme”-worthy footnote: “The maiden who posed for the original of ‘The Sower’ on this stamp died in abject poverty in later years — a story with a tear drop at the end.”

on the next page. Why the two sets with the same design? Je ne sais pas, monsieurs-dames! I only ask that you agree with me that this allegory is an altogether pleasing figure. It is modeled after a medallion designed by Oscar Roty for the Department of Agriculture in the 1880s. The image appeared on French coins until 2001. An old Stampex pamphlet provides this “La Boheme”-worthy footnote: “The maiden who posed for the original of ‘The Sower’ on this stamp died in abject poverty in later years — a story with a tear drop at the end.” T

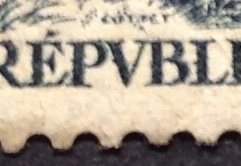

T his set (left) is an exception to the rule of the feminine — a depiction of Mercury on a definitive series. This one came out in 1938. After the Nazis invaded and occupied France in 1940, the collaborationist Vichy regime put out new stamps with a subtle change in the name — from “Republique Francaise” to “Postes Francaises.” (see enlargement below)

his set (left) is an exception to the rule of the feminine — a depiction of Mercury on a definitive series. This one came out in 1938. After the Nazis invaded and occupied France in 1940, the collaborationist Vichy regime put out new stamps with a subtle change in the name — from “Republique Francaise” to “Postes Francaises.” (see enlargement below)

This set, depicting Iris, the Greek goddess of the rainbow and messenger of the gods, was issued in 1939. My catalogue says the stamps were in circulation until 1944, which means they were used during the German occupation. Hmm.

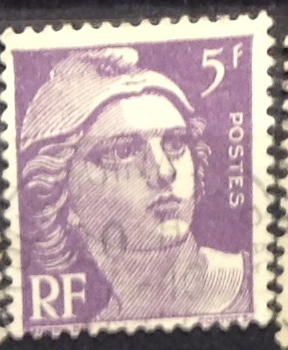

This set, depicting Iris, the Greek goddess of the rainbow and messenger of the gods, was issued in 1939. My catalogue says the stamps were in circulation until 1944, which means they were used during the German occupation. Hmm. These stamps, with the bust of a helmeted Marianne (or is it Joan of Arc?), were issued in London during World War II by direction of the Free French government. Apparently they were never used for postage. There seem to be wild fluctuations in value for these stamps — I suspect mine are at the low end, but some varieties are priced in the hundreds.

These stamps, with the bust of a helmeted Marianne (or is it Joan of Arc?), were issued in London during World War II by direction of the Free French government. Apparently they were never used for postage. There seem to be wild fluctuations in value for these stamps — I suspect mine are at the low end, but some varieties are priced in the hundreds. H

H ere is the familiar postwar definitive set (1945-7), once again depicting Marianne. This beauty has a wholly Gallic expression — confident, alert, focused, slightly pouty lips, prominent nose, wary eyes on the future. Notice, too, the low-value designs (enlarged below) that incorporate the Ceres profile from the first French stamp of 1849 — about which more, shortly.

ere is the familiar postwar definitive set (1945-7), once again depicting Marianne. This beauty has a wholly Gallic expression — confident, alert, focused, slightly pouty lips, prominent nose, wary eyes on the future. Notice, too, the low-value designs (enlarged below) that incorporate the Ceres profile from the first French stamp of 1849 — about which more, shortly.

E

E

xcept now, qu’est que c’est? What is this? Is it really Marianne, the emblem of France? She looks like a cross between Bardot and Barbarella, a Victoria’s Secret model with tresses casually arranged and sculpted eyebrows under her chic Phrygian cap. Is she really going to lead the next revolution?

xcept now, qu’est que c’est? What is this? Is it really Marianne, the emblem of France? She looks like a cross between Bardot and Barbarella, a Victoria’s Secret model with tresses casually arranged and sculpted eyebrows under her chic Phrygian cap. Is she really going to lead the next revolution? I mentioned Ceres a little earlier — another feminine allegory, the goddess of Earth and fertility. I invite you now to the very beginning of French stamps. The first one had a profile of Ceres, and came out in 1849, a very awkward moment in French history. The Second Republic was in the second year of its short existence, having ousted Louis Philippe, France’s last king, after the confusing revolution of 1848. (I majored in French and German intellectual history at Harvard, and I still can’t explain it to you.) By 1852, the Second Republic had morphed into the French Empire under Napoleon III, who would soldier on until 1870 and the birth of the Third Republic, which endured until 1940.

I mentioned Ceres a little earlier — another feminine allegory, the goddess of Earth and fertility. I invite you now to the very beginning of French stamps. The first one had a profile of Ceres, and came out in 1849, a very awkward moment in French history. The Second Republic was in the second year of its short existence, having ousted Louis Philippe, France’s last king, after the confusing revolution of 1848. (I majored in French and German intellectual history at Harvard, and I still can’t explain it to you.) By 1852, the Second Republic had morphed into the French Empire under Napoleon III, who would soldier on until 1870 and the birth of the Third Republic, which endured until 1940.

This explains why the first French stamps, in 1849,

This explains why the first French stamps, in 1849,

“uprising” referenced in that novel was a pretty minor skirmish in 1832.) 1860 was one year before the U.S. Civil War, the same year Abraham Lincoln was elected to his first term.

“uprising” referenced in that novel was a pretty minor skirmish in 1832.) 1860 was one year before the U.S. Civil War, the same year Abraham Lincoln was elected to his first term. This next design, launched in 1876 and lasting until the turn of the century, depicts two more allegories — in this case, one male, one female. On

This next design, launched in 1876 and lasting until the turn of the century, depicts two more allegories — in this case, one male, one female. On my father’s collection, with enlargements to the right. Some of these stamps are quite valuable: The 5f mint stamp from the 1870s catalogues at $400!

my father’s collection, with enlargements to the right. Some of these stamps are quite valuable: The 5f mint stamp from the 1870s catalogues at $400!

from religious persecution at home. Likewise, among the Dutch and German adventurers who landed near the tip of southern Africa in the same century were French Huguenots, fleeing persecution for their faith. Dutch navigators Jan van Riebeeck sailed to the Cape of Good Hope, found safe harbor for his ships in Table Bay in 1652 and went on to

from religious persecution at home. Likewise, among the Dutch and German adventurers who landed near the tip of southern Africa in the same century were French Huguenots, fleeing persecution for their faith. Dutch navigators Jan van Riebeeck sailed to the Cape of Good Hope, found safe harbor for his ships in Table Bay in 1652 and went on to

In the end, I would simply offer this rationale for my leap into these deep waters with the FMF Stamp Project; it is the justification for all historical study: to know how we got here. How did the “British South Africa Company” become Zimbabwe? How did the Cape of Good Hope turn into the Republic of South Africa? What happened to Transvaal, Natal, Zululand, the Orange Free State, the New Republic, Stellaland, Griqualand West? (Not to mention Griqualand East?) Why did Bechuanaland split apart? Answering these

In the end, I would simply offer this rationale for my leap into these deep waters with the FMF Stamp Project; it is the justification for all historical study: to know how we got here. How did the “British South Africa Company” become Zimbabwe? How did the Cape of Good Hope turn into the Republic of South Africa? What happened to Transvaal, Natal, Zululand, the Orange Free State, the New Republic, Stellaland, Griqualand West? (Not to mention Griqualand East?) Why did Bechuanaland split apart? Answering these

colonialism combine much of today’s conventional wisdom with another possibility. I agree the colonial enterprise in Africa

colonialism combine much of today’s conventional wisdom with another possibility. I agree the colonial enterprise in Africa

from the 1850s, and a hand-stamped emergency issue of 1900 from the Cape of Good Hope, overprinted “Mafeking Besieged.” So please —

from the 1850s, and a hand-stamped emergency issue of 1900 from the Cape of Good Hope, overprinted “Mafeking Besieged.” So please —  read on!

read on!

nothing can ruin the value of a mint stamp quicker than a drop of water.

nothing can ruin the value of a mint stamp quicker than a drop of water.

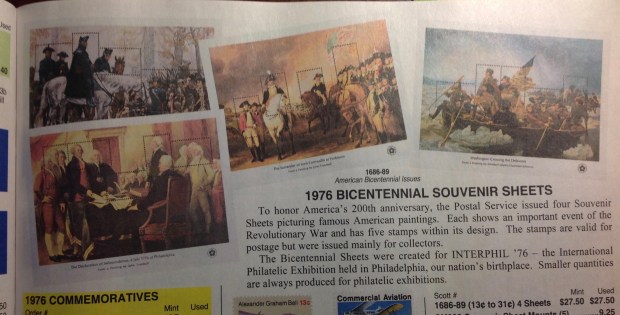

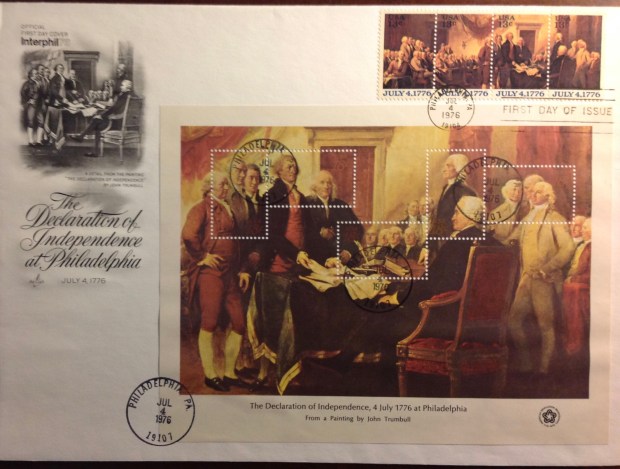

its wisdom to issue a four-stamp set July 4, displaying a wider view of the same painting that appeared on one of the souvenir sheets — signing of the Declaration — with the inscription, “July 4, 1776.” (see right). I took advantage of the situation by affixing that set, along with the souvenir sheet containing a detail of the same design, to an oversize envelope bearing

its wisdom to issue a four-stamp set July 4, displaying a wider view of the same painting that appeared on one of the souvenir sheets — signing of the Declaration — with the inscription, “July 4, 1776.” (see right). I took advantage of the situation by affixing that set, along with the souvenir sheet containing a detail of the same design, to an oversize envelope bearing

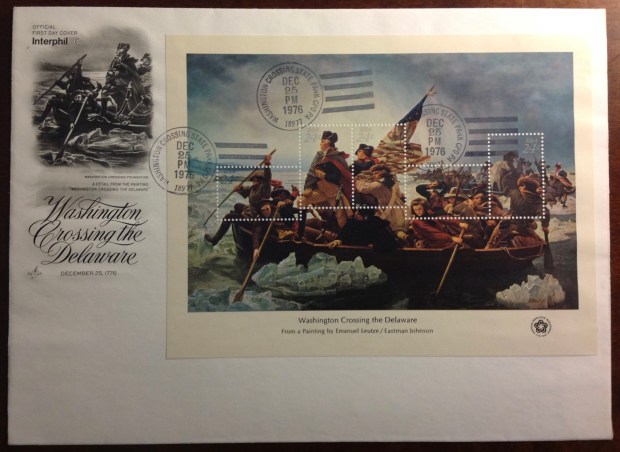

I concocted back in May 1976, when the Bicentennial souvenir sheets were issued (see right). First I broke up one of the “Yorktown” sheets, and must have used three of the five embedded stamps for postage on letters. The other two stamps, still intact with the sheet remnant, I stuck to a commemorative envelope, put my address on it and had it sent to me across town through the mail, complete with the first-day cancel. Any idea what a partial first-day cover is worth?

I concocted back in May 1976, when the Bicentennial souvenir sheets were issued (see right). First I broke up one of the “Yorktown” sheets, and must have used three of the five embedded stamps for postage on letters. The other two stamps, still intact with the sheet remnant, I stuck to a commemorative envelope, put my address on it and had it sent to me across town through the mail, complete with the first-day cancel. Any idea what a partial first-day cover is worth?

Now consider: I have recovered each of the five stamps on the bicentennial sheets (pictured above). Removed from their surroundings in the damaged sheets, they take on a whole different aspect. If you examine them one by one, you may conclude, as I do,

Now consider: I have recovered each of the five stamps on the bicentennial sheets (pictured above). Removed from their surroundings in the damaged sheets, they take on a whole different aspect. If you examine them one by one, you may conclude, as I do,

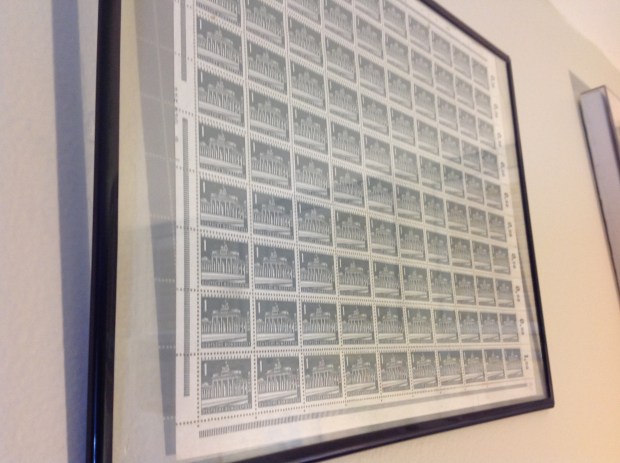

The last two frames I offer for your inspection, at right, represent a considerable labor of love on my part. I patiently accumulated cancelled copies of each one of the 50 values in the 20-cent state-birds-and-flowers series of 1982. (Back then I was a newspaperman and had access to tons of mail.) Then I mounted the set, in alphabetical order of the states, on two grids and framed them. Cute, eh? At first the frames didn’t appear to have suffered damage, but when I started to lift the glass out of one frame, some of the stamps stuck and

The last two frames I offer for your inspection, at right, represent a considerable labor of love on my part. I patiently accumulated cancelled copies of each one of the 50 values in the 20-cent state-birds-and-flowers series of 1982. (Back then I was a newspaperman and had access to tons of mail.) Then I mounted the set, in alphabetical order of the states, on two grids and framed them. Cute, eh? At first the frames didn’t appear to have suffered damage, but when I started to lift the glass out of one frame, some of the stamps stuck and  started to come apart. I stopped immediately, returned the glass to the frame and let it be. What to do now? Since these are used stamps, I suppose I could soak them off in water (!) and even assemble another two-frame display

started to come apart. I stopped immediately, returned the glass to the frame and let it be. What to do now? Since these are used stamps, I suppose I could soak them off in water (!) and even assemble another two-frame display

My first memorable encounter with philately came when I was about six, in 1954, at The Pigeon House, a drafty converted coop-barn that my family stayed in for several summers near the south shore in Marshfield, Mass. It was part of the “farm” on Pudding Hill Lane that

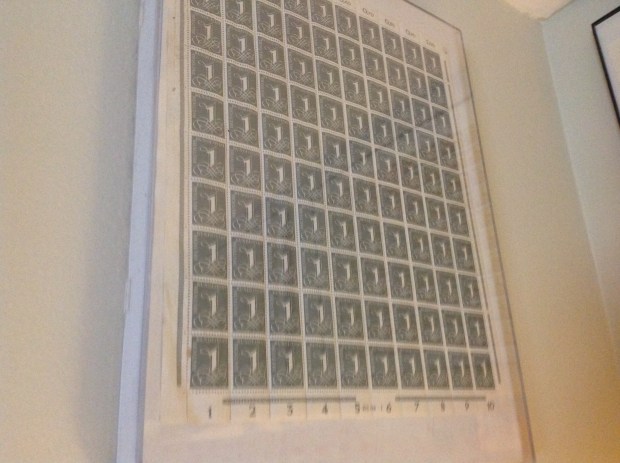

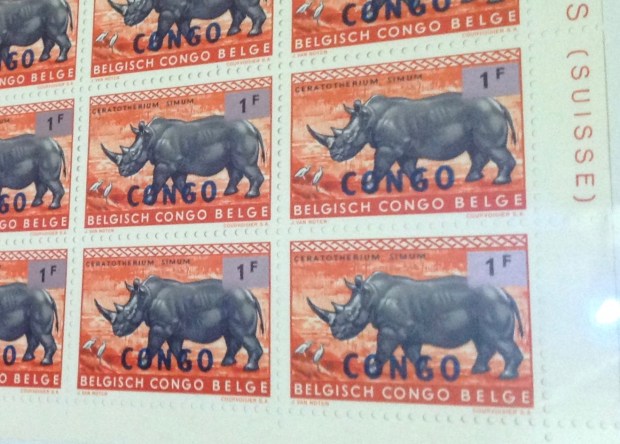

My first memorable encounter with philately came when I was about six, in 1954, at The Pigeon House, a drafty converted coop-barn that my family stayed in for several summers near the south shore in Marshfield, Mass. It was part of the “farm” on Pudding Hill Lane that The image at right is from the line-up of framed stamp sheets from Congo on the wall of my study (see above). The stamps originally were issued for the Belgian Congo, overprinted at independence — then overprinted again in subsequent years. This stamp started out as the 1f50 value from the flowers series of 1953, which was overprinted “CONGO” and became the first definitive set of independent Congo in 1960. In 1964 it was surcharged in black on silver, as Congo lurched toward ruin in the hands of Mobutu Sese Seko.

The image at right is from the line-up of framed stamp sheets from Congo on the wall of my study (see above). The stamps originally were issued for the Belgian Congo, overprinted at independence — then overprinted again in subsequent years. This stamp started out as the 1f50 value from the flowers series of 1953, which was overprinted “CONGO” and became the first definitive set of independent Congo in 1960. In 1964 it was surcharged in black on silver, as Congo lurched toward ruin in the hands of Mobutu Sese Seko.

In this pair of images and the next pair you will find two examples of what was once the 20 centime stamp from the Belgian Congo 1959 animal series, overprinted “Congo” in the second definitive set after independence in 1960. Here the original 1959 stamp carries a silver overlay

In this pair of images and the next pair you will find two examples of what was once the 20 centime stamp from the Belgian Congo 1959 animal series, overprinted “Congo” in the second definitive set after independence in 1960. Here the original 1959 stamp carries a silver overlay

This

This

OK, let’s really get into it. If you like, run quickly through this pair of images and the next two pairs., then come back…. On first glance, all the stamps look alike, right? Well, they started out being the same — the 6f50

OK, let’s really get into it. If you like, run quickly through this pair of images and the next two pairs., then come back…. On first glance, all the stamps look alike, right? Well, they started out being the same — the 6f50

Above my desk you will find a Stamp Map (above) — the world laid out before me, with stamps from many nations attached to their country of origin. Seems like it’s always been there on the wall … a bit like that bathroom at The Pigeon House, eh?

Above my desk you will find a Stamp Map (above) — the world laid out before me, with stamps from many nations attached to their country of origin. Seems like it’s always been there on the wall … a bit like that bathroom at The Pigeon House, eh?

This series (above and rifght) confirms the wisdom of my decision to frame and display my stamps. There’s just no other good way to handle these stamps! It’s from just a few years ago, an issue with 60 values, one for each state and a number of “generic” USA stamps.

This series (above and rifght) confirms the wisdom of my decision to frame and display my stamps. There’s just no other good way to handle these stamps! It’s from just a few years ago, an issue with 60 values, one for each state and a number of “generic” USA stamps. Here is another enchanting exhibit. A few years ago, the USPS issued a series of low-value definitive stamps featuring vintage designs — jewelry and household furnishings. The charming, full-color vignettes had colorful backgrounds and common design features for each value — 1c, 2c, 3c, 4c, 5c and 10c.

Here is another enchanting exhibit. A few years ago, the USPS issued a series of low-value definitive stamps featuring vintage designs — jewelry and household furnishings. The charming, full-color vignettes had colorful backgrounds and common design features for each value — 1c, 2c, 3c, 4c, 5c and 10c.

These beautiful landscape paintings appeared in a series of 12 sheets under the heading, “Nature of America.” The sheets were designed and executed so that you could identify easily the essential information — “USA 33” — to locate the stamps within the sheet. You’d just peel off stamps as you needed them. If you look closely, each stamp has a design that stands on its own. Clever. Sort of like a loopy version of an advent calendar. Or a sticker book in reverse.

These beautiful landscape paintings appeared in a series of 12 sheets under the heading, “Nature of America.” The sheets were designed and executed so that you could identify easily the essential information — “USA 33” — to locate the stamps within the sheet. You’d just peel off stamps as you needed them. If you look closely, each stamp has a design that stands on its own. Clever. Sort of like a loopy version of an advent calendar. Or a sticker book in reverse. At left are enlarged versions of a couple of the sheets, one featuring a Pacific Coral Reef, the other the Sonoran Desert. All the sheets are worth a look, and they are not expensive — about 60 bucks for all 12. Other scenes depict the

At left are enlarged versions of a couple of the sheets, one featuring a Pacific Coral Reef, the other the Sonoran Desert. All the sheets are worth a look, and they are not expensive — about 60 bucks for all 12. Other scenes depict the  Pacific Rain Forest, the Great Plains Prairie, Southern Florida Wetland, Northeast Deciduous Forest, Alpine Tundra, Great Lakes Dunes, Kelp Forest, Hawaiian Rain Forest, Longleaf Pine Forest and Arctic Tundra.

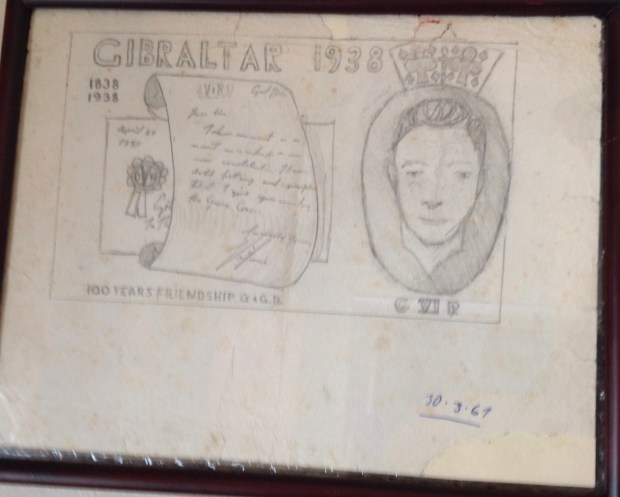

Pacific Rain Forest, the Great Plains Prairie, Southern Florida Wetland, Northeast Deciduous Forest, Alpine Tundra, Great Lakes Dunes, Kelp Forest, Hawaiian Rain Forest, Longleaf Pine Forest and Arctic Tundra. These final “stamps” on display aren’t really stamps at all, but rather my own fanciful designs for imaginary sets from exotic lands, concocted during my teenage years when I actually lived in exotic lands like Congo and Germany (but not Ghana or Australia).

These final “stamps” on display aren’t really stamps at all, but rather my own fanciful designs for imaginary sets from exotic lands, concocted during my teenage years when I actually lived in exotic lands like Congo and Germany (but not Ghana or Australia).

Finally, here is my display (right and below) of the “state quarters” that started appearing over the past decade. I had no idea, when daughter Tanika and I crafted this display, that the US Mint would keep issuing quarters for all sorts of monuments and moments. I have more than a dozen waiting to be added to my collection — but how will I fit them in? And will the practice of churning out new quarters never end?

Finally, here is my display (right and below) of the “state quarters” that started appearing over the past decade. I had no idea, when daughter Tanika and I crafted this display, that the US Mint would keep issuing quarters for all sorts of monuments and moments. I have more than a dozen waiting to be added to my collection — but how will I fit them in? And will the practice of churning out new quarters never end?

If you have paid close attention to my stamp blog, you know I have a nice copy of Great Britain No. 1 — the world’s first postage stamp, also known as the Penny Black. (see right)

If you have paid close attention to my stamp blog, you know I have a nice copy of Great Britain No. 1 — the world’s first postage stamp, also known as the Penny Black. (see right) Take, for example, this early two-color British India stamp of 1854, featuring an imperforate octagonal frame with a portrait of Queen Victoria (right, from the Internet). A nice copy like this pretty stamp (grabbed from the Internet) will sell for up to $450.

Take, for example, this early two-color British India stamp of 1854, featuring an imperforate octagonal frame with a portrait of Queen Victoria (right, from the Internet). A nice copy like this pretty stamp (grabbed from the Internet) will sell for up to $450.

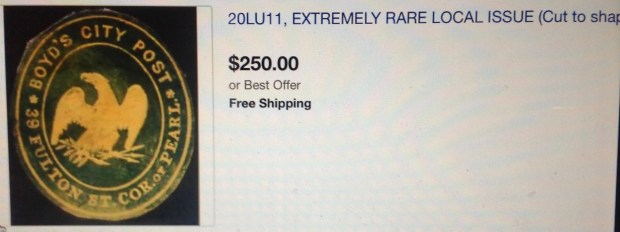

Here is an example, from the Internet, of the 4-anna stamp, cut to shape. It’s not cheap, but much below the cost of a rectangle. Get my point?

Here is an example, from the Internet, of the 4-anna stamp, cut to shape. It’s not cheap, but much below the cost of a rectangle. Get my point? For starters, take a look at this beauty (right). It’s the famous British Guiana one-cent black-on-magenta, a fabled one-of-a-kind variety. And as you’ll notice, it’s cut to shape. That doesn’t prevent it being sold and re-sold, every now and then, for millions.

For starters, take a look at this beauty (right). It’s the famous British Guiana one-cent black-on-magenta, a fabled one-of-a-kind variety. And as you’ll notice, it’s cut to shape. That doesn’t prevent it being sold and re-sold, every now and then, for millions.

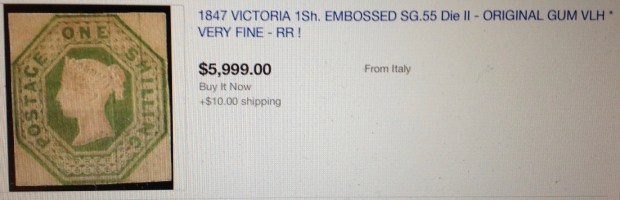

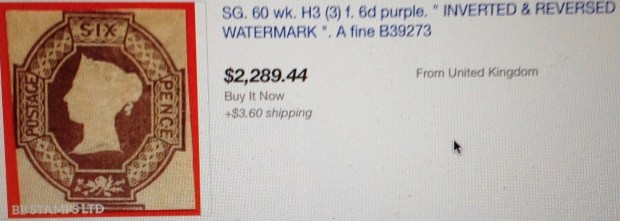

More common are examples like these, also from the Internet. Notice the relatively low price for these ancient embossed beauties. They’d be worth a lot

More common are examples like these, also from the Internet. Notice the relatively low price for these ancient embossed beauties. They’d be worth a lot  more if they were not cut to shape.

more if they were not cut to shape.

Whatever value the medallion-shaped oddment here had was decimated by the lame-brained stamp fiend who cut it to shape. (Was it a younger me?)

Whatever value the medallion-shaped oddment here had was decimated by the lame-brained stamp fiend who cut it to shape. (Was it a younger me?) This is a cute enough collection, and they’re all nice rectangles. Not worth much, though.

This is a cute enough collection, and they’re all nice rectangles. Not worth much, though. As I segue back to my quest for those early GB embossed stamps, I offer this: the world’s first “envelope stamp.” It’s from 1840 in Great Britain, and it’s known as the Mulready Cover — a one-penny foldable sheet you could write on, seal up and send through the mail. The idea never caught on. (This nice example is from my collection; I expect it’s worth at least the

As I segue back to my quest for those early GB embossed stamps, I offer this: the world’s first “envelope stamp.” It’s from 1840 in Great Britain, and it’s known as the Mulready Cover — a one-penny foldable sheet you could write on, seal up and send through the mail. The idea never caught on. (This nice example is from my collection; I expect it’s worth at least the  $40 I paid for it.)

$40 I paid for it.) some kind of holographic horror representing the space program or something like that.

some kind of holographic horror representing the space program or something like that.

It was growing clear to me that if I ever wanted to fill those empty spaces in my album, I would have to settle for cut-to-shape. But I didn’t just want a “space-filler,” a crudely mangled example that is essentially worthless. Over the years, the Scott catalogue has upgraded its price for Nos. 5-7, cut to

It was growing clear to me that if I ever wanted to fill those empty spaces in my album, I would have to settle for cut-to-shape. But I didn’t just want a “space-filler,” a crudely mangled example that is essentially worthless. Over the years, the Scott catalogue has upgraded its price for Nos. 5-7, cut to  shape, from $1.50 to $10 or so. I searched the Internet and began finding cut-to-shape offerings that were well within my price range. There were flaws, though.

shape, from $1.50 to $10 or so. I searched the Internet and began finding cut-to-shape offerings that were well within my price range. There were flaws, though. Finally I came across this cute little item: No. 5, carefully cut to shape, including nearly the entire design; no thins, tears or creases; offered for sale at $14.99.

Finally I came across this cute little item: No. 5, carefully cut to shape, including nearly the entire design; no thins, tears or creases; offered for sale at $14.99.

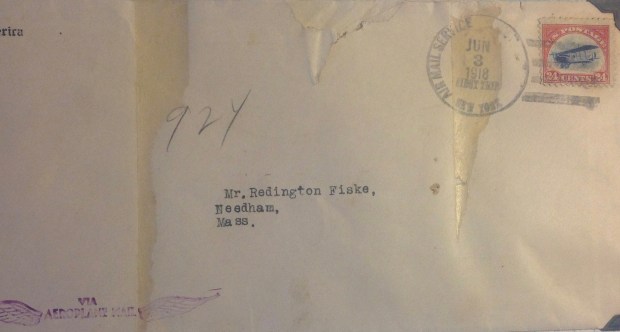

In 2013, the US Postal Service issued a souvenir sheet depicting the inverted Jenny — the same engraving and colors as the accidental error back in 1918, as far as I can tell, only with a $2 value instead of 24 cents. It’s a beautiful, interesting sheet, full of information on the back. The stamps showing the famous upside-down plane are worth at least, well, two dollars each.

In 2013, the US Postal Service issued a souvenir sheet depicting the inverted Jenny — the same engraving and colors as the accidental error back in 1918, as far as I can tell, only with a $2 value instead of 24 cents. It’s a beautiful, interesting sheet, full of information on the back. The stamps showing the famous upside-down plane are worth at least, well, two dollars each.

It bears the 24-cent “Jenny” airmail stamp, issued just three weeks before on May 13, 1918, cancelled with the message in the circular cancel: “Air Mail Service; New York; Jun 3, 1918; First Trip.” The return address is the “Aerial League of America,” 297 Madison Avenue. A rubber stamp in the lower left corner of the envelope announces: “VIA Aeroplane Mail.” Quaint! While the envelope isn’t in particularly good shape, a similar “first flight” cover was offered on eBay recently — for $250!

It bears the 24-cent “Jenny” airmail stamp, issued just three weeks before on May 13, 1918, cancelled with the message in the circular cancel: “Air Mail Service; New York; Jun 3, 1918; First Trip.” The return address is the “Aerial League of America,” 297 Madison Avenue. A rubber stamp in the lower left corner of the envelope announces: “VIA Aeroplane Mail.” Quaint! While the envelope isn’t in particularly good shape, a similar “first flight” cover was offered on eBay recently — for $250! Do you think it was magnanimous of the British to grant “internal self government” to its Bechuanaland territory in 1965

Do you think it was magnanimous of the British to grant “internal self government” to its Bechuanaland territory in 1965 Then an odd little set came out June 1, 1966, commemorating the Bechuanaland Pioneers and Gunners. These were African “recruits” in World War II, as many as 10,000 Tswana in all. Some volunteered, others were pressed into service as laborers, anti-aircraft gunners and drivers. African troops traveled as far as Italy and Lebanon. This set marked the 25th anniversary of the Bechuanaland pioneers, formed in 1941 and disbanded in 1946. The designs include a British Hasler smoke generator truck with Bechuana operators, and a

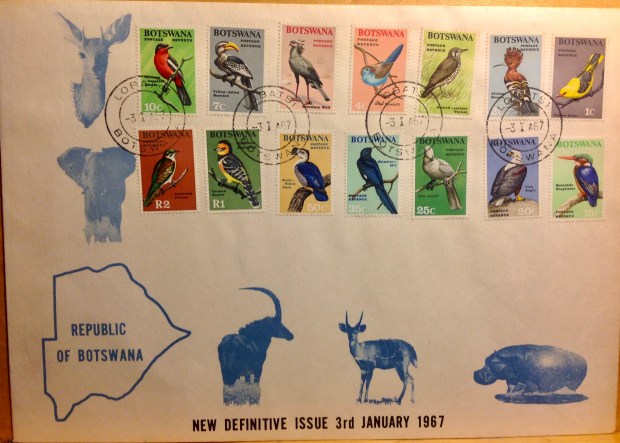

Then an odd little set came out June 1, 1966, commemorating the Bechuanaland Pioneers and Gunners. These were African “recruits” in World War II, as many as 10,000 Tswana in all. Some volunteered, others were pressed into service as laborers, anti-aircraft gunners and drivers. African troops traveled as far as Italy and Lebanon. This set marked the 25th anniversary of the Bechuanaland pioneers, formed in 1941 and disbanded in 1946. The designs include a British Hasler smoke generator truck with Bechuana operators, and a Three months later, a new nation was born — philatelically speaking. The first set from independent Botswana was issued Sept. 30, 1966, and was clearly a rush job: Instead of designing new stamps for the new country, postal authorities simply overprinted the 1962 definitive set with “Republic of Botswana.” OK, so it looks kind of weird to have Queen Elizabeth smiling out from under the overprint. But hey, the stamps are valid enough. Lots of emancipated colonies did the same thing, starting with Ghana, which overprinted the Gold Coast set of Queen Elizabeth definitives in 1956.

Three months later, a new nation was born — philatelically speaking. The first set from independent Botswana was issued Sept. 30, 1966, and was clearly a rush job: Instead of designing new stamps for the new country, postal authorities simply overprinted the 1962 definitive set with “Republic of Botswana.” OK, so it looks kind of weird to have Queen Elizabeth smiling out from under the overprint. But hey, the stamps are valid enough. Lots of emancipated colonies did the same thing, starting with Ghana, which overprinted the Gold Coast set of Queen Elizabeth definitives in 1956. Above is the first definitive set designed specifically for Botswana. An earlier

Above is the first definitive set designed specifically for Botswana. An earlier At right is a display in my stock album of stamps from several

At right is a display in my stock album of stamps from several intent— when they come my way, I take them. I still enjoy putting sets together, noticing common features as well as the obvious and subtle differences. Somehow, it just makes life sweeter.

intent— when they come my way, I take them. I still enjoy putting sets together, noticing common features as well as the obvious and subtle differences. Somehow, it just makes life sweeter. I must pass along a blow-up of this unusual Botswana commemorative from 1975. It celebrates the 90th anniversary of the

I must pass along a blow-up of this unusual Botswana commemorative from 1975. It celebrates the 90th anniversary of the Above is what we in the philately racket call a “hodge-podge.” It’s a catch-all page in my stock album for post-colonial Africa, my last page for Botswana. You will see some attractive animal stamps, and a crudely-drawn portrait of two nearly naked

Above is what we in the philately racket call a “hodge-podge.” It’s a catch-all page in my stock album for post-colonial Africa, my last page for Botswana. You will see some attractive animal stamps, and a crudely-drawn portrait of two nearly naked The set at lower left above (enlarged at right) commemorates a century of Bechuanaland stamps, carrying us back to where we began. You can read much more about this set — and the stories the stamps tell — in my blog post of April 2018, Bechuanaland: Introduction. That is where my exploration of Bechuanaland/Botswana and its stamps began.

The set at lower left above (enlarged at right) commemorates a century of Bechuanaland stamps, carrying us back to where we began. You can read much more about this set — and the stories the stamps tell — in my blog post of April 2018, Bechuanaland: Introduction. That is where my exploration of Bechuanaland/Botswana and its stamps began.