At last! A consummation devoutly to be wished. Or should I say, a resumption long overdue. I think it was about 500 pages and two years back that I temporarily abandoned my original mission in this FMF Stamp Project — which was a leisurely ramble through the storied landscape of my stamp collection, starting with British Africa. I got through my collection from the British Colony of Ascension Island, and also the small southern African territory of Basutoland (now Lesotho). Then I went my merry way, with long diversions to Congo, other precincts of that vast continent, and into various fjords and flights that led eventually to a 150-page examination of so-called “Cinderella” stamps (that is, stamps that are not real stamps). That topic, by the way, is far from exhausted, though I needed a breather!

At last! A consummation devoutly to be wished. Or should I say, a resumption long overdue. I think it was about 500 pages and two years back that I temporarily abandoned my original mission in this FMF Stamp Project — which was a leisurely ramble through the storied landscape of my stamp collection, starting with British Africa. I got through my collection from the British Colony of Ascension Island, and also the small southern African territory of Basutoland (now Lesotho). Then I went my merry way, with long diversions to Congo, other precincts of that vast continent, and into various fjords and flights that led eventually to a 150-page examination of so-called “Cinderella” stamps (that is, stamps that are not real stamps). That topic, by the way, is far from exhausted, though I needed a breather!

I’ve been circling back toward Bechuanaland, the next country by alphabetical order in my British Africa album. I got so far as to present a solid introduction to the topic (see Bechuanaland: Introduction blog post, April 2018). Then other subjects and stories drew my attention. There’s just so much of interest in the world of stamps, don’t you think?

Continuing to circle, I touched on Bechuanaland in my tale of the elusive five-pound Victorian, then managed to work it into my short exploration of “Fiscals” (a branch of Cinderellas that goes on and on). The happy outcome of that short tale was that I acquired the Bechuanaland one-pound Victorian, which you will see again, shortly.

Hooray! Here we are, ready or not. Just to recap: As I’ve already explained, in the 1880s, the British divided Bechuanaland into a protectorate (Bechuanaland Protectorate) and a crown colony (British Bechuanaland). The protectorate survived until 1966, when it became the independent republic of Botswana. The British colony became part of the southern African nexus, and was absorbed into the Union of South Africa in 1910. Bechuanaland/Botswana has a colorful history (see 4/18 blog post for more). Now it’s time for stamps!

British Africa (continued), Bechuanaland, page one:

Issues of 1886-7. OK, here we go. Actually, this is a piece of stamp-cake. I figure the best way to proceed is to offer a kind of thumbnail view of the album page (right), then enlarge the stamp images and expound on them.

The first stamps from “British Bechuanaland,” shown below, are overprints of Cape of Good Hope stamps. There would be many iterations of these overprints in the next few years, both for British Bechuanaland and Bechuanaland Protectorate. I have a decent showing here. Let me tell you, the ones I am missing are not cheap!

A word on the legend provided in my stamp album (see right). You may notice that it refers to British Bechuanaland as a “high commission territory” in 1960. This is nonsense. Bechuanaland Protectorate was indeed under British supervision in 1960 — independent Botswana was still six years off. But British Bechuanaland? It didn’t even exist after 1895, first merging with the Cape Colony, then the Union of South Africa.

A word on the legend provided in my stamp album (see right). You may notice that it refers to British Bechuanaland as a “high commission territory” in 1960. This is nonsense. Bechuanaland Protectorate was indeed under British supervision in 1960 — independent Botswana was still six years off. But British Bechuanaland? It didn’t even exist after 1895, first merging with the Cape Colony, then the Union of South Africa.

I believe I have rhapsodized about this set (above) before — how the designs look like bas-reliefs profiles of the Queen carved into tablets of rose marble or granite. Drab, you say? OK, the lilac color doesn’t jump out at you, and it’s the same for the 1d, 2d, 3d, 4d and 6d, before changing to a decidedly unglamorous shade of green for the 1/- through 10/- values. And then, for the one-pound and five-pound values, it reverts to the same faded lilac color. Sigh.

I believe I have rhapsodized about this set (above) before — how the designs look like bas-reliefs profiles of the Queen carved into tablets of rose marble or granite. Drab, you say? OK, the lilac color doesn’t jump out at you, and it’s the same for the 1d, 2d, 3d, 4d and 6d, before changing to a decidedly unglamorous shade of green for the 1/- through 10/- values. And then, for the one-pound and five-pound values, it reverts to the same faded lilac color. Sigh.

But wait! I will have none of it! That lilac, to begin with, is worthy of Miss Haversham’s parlor, or the most delicate hydrangea in a garden at Wellfleet. Furthermore, the design consistency is a bedrock quality of this set, providing a sense of stability and order that can only have helped in the remote precincts of British Bechuanaland in 1888.

Bechuanaland, page two: Issues of 1888-98. Just a few comments on this page. There is always something to say!

Bechuanaland, page two: Issues of 1888-98. Just a few comments on this page. There is always something to say!  Notice at right how the earlier set has been surcharged — with the same value spelled out in the tablets flanking the portrait! I guess too many postal customers needed to see a number …

Notice at right how the earlier set has been surcharged — with the same value spelled out in the tablets flanking the portrait! I guess too many postal customers needed to see a number …

At right, top row, is a remarkable sequence that captures all the wackiness of British Bechuanaland bureaucracy. Here we have the overprints running across top and bottom, sideways left, and sideways right. Whew! Make up your minds! (As you can see, from the pencil notations, I paid good bucks for these — $13 for the 1/2d, for example.

At right, top row, is a remarkable sequence that captures all the wackiness of British Bechuanaland bureaucracy. Here we have the overprints running across top and bottom, sideways left, and sideways right. Whew! Make up your minds! (As you can see, from the pencil notations, I paid good bucks for these — $13 for the 1/2d, for example.

The second row is a complete set of GB overprints of the Victoria sexagenary jubilee set. Not bad!

Bechuanaland, page three: Issues of 1888-97. Notice the subtle difference in these stamps. The overprint has

Bechuanaland, page three: Issues of 1888-97. Notice the subtle difference in these stamps. The overprint has  changed from “British Bechuanaland” to “Bechuanaland Protectorate.” It took me years to collect all of these…

changed from “British Bechuanaland” to “Bechuanaland Protectorate.” It took me years to collect all of these…

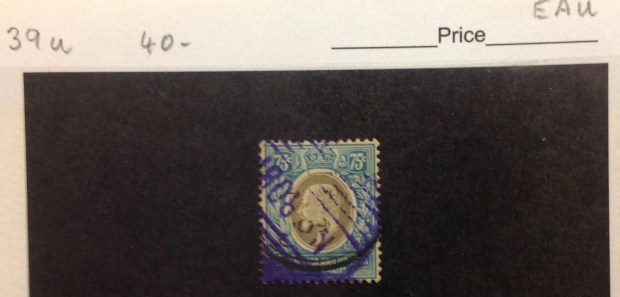

Bechuanaland, page four: Issues of 1904-27. By now “British Bechuanaland” was just a memory — but “Bechuanaland Protectorate” would last 80 years. For

Bechuanaland, page four: Issues of 1904-27. By now “British Bechuanaland” was just a memory — but “Bechuanaland Protectorate” would last 80 years. For  nearly three decades, postal authorities made do with these undistinguished overprints of British definitives — through the reign of Edward VII and well into that of George V. What a missed opportunity!

nearly three decades, postal authorities made do with these undistinguished overprints of British definitives — through the reign of Edward VII and well into that of George V. What a missed opportunity!

Bechuanaland, page five: Issues of 1926-35. You may be able to identify on this page, reproduced at right, a “postage due” set at the top, another one in the middle, and at the bottom of the page the familiar “omnibus” set commemorating George V’s 25th anniversary on the throne, on the verge of his death in 1935. No need to dwell on them here.

Bechuanaland, page five: Issues of 1926-35. You may be able to identify on this page, reproduced at right, a “postage due” set at the top, another one in the middle, and at the bottom of the page the familiar “omnibus” set commemorating George V’s 25th anniversary on the throne, on the verge of his death in 1935. No need to dwell on them here.

What I want to swoon over is this gorgeous set of George V definitives that appeared in 1932. Aren’t they beauties?  Sorry I don’t have the higher values (yet). They are quite dear.

Sorry I don’t have the higher values (yet). They are quite dear.  However, please enjoy the delicate artistry of the engraving of a pastoral Tswana landscape that features grazing cattle and a venerable baobab tree.

However, please enjoy the delicate artistry of the engraving of a pastoral Tswana landscape that features grazing cattle and a venerable baobab tree.

Bechuanaland, page six: 1937-45. The king is dead. Long live the king. That’s the way it was in the British Empire. George V expired Jan. 20, 1936, and after the business with Edward VIII, George VI was duly coronated in 1937. Without missing a beat, the engravers substituted a portrait of the young king for that of his late father, and the same beautiful design remained in use through the 15 years of his reign. Notice the exquisite color combinations for the upper values — black and olive green (1/-); black

Bechuanaland, page six: 1937-45. The king is dead. Long live the king. That’s the way it was in the British Empire. George V expired Jan. 20, 1936, and after the business with Edward VIII, George VI was duly coronated in 1937. Without missing a beat, the engravers substituted a portrait of the young king for that of his late father, and the same beautiful design remained in use through the 15 years of his reign. Notice the exquisite color combinations for the upper values — black and olive green (1/-); black  and carmine (2/6); black and ultramarine (5/-); black and red-brown (10/-). This complete set, mint, was selling today online for $42.50.

and carmine (2/6); black and ultramarine (5/-); black and red-brown (10/-). This complete set, mint, was selling today online for $42.50.

This set again! You may remember it from the Basutoland pages — same South Africa set, same patriotic themes, same white faces enjoying the end of World War II.

This set again! You may remember it from the Basutoland pages — same South Africa set, same patriotic themes, same white faces enjoying the end of World War II.

Bechuanaland, page seven: Issues of 1947-9. No need to dwell on this page, which features “omnibus” issues for the Royals’ 25th wedding anniversary (which I don’t have), the Royal Visit of 1947, and the Universal Postal Union issue of 1949. Why do I bother to collect these stamps, which aren’t valuable? I guess I just like to keep striving for completeness …

Bechuanaland, page seven: Issues of 1947-9. No need to dwell on this page, which features “omnibus” issues for the Royals’ 25th wedding anniversary (which I don’t have), the Royal Visit of 1947, and the Universal Postal Union issue of 1949. Why do I bother to collect these stamps, which aren’t valuable? I guess I just like to keep striving for completeness …

Bechuanaland, page eight: Issues of 1953-60. Guess what happened after 1953, when Elizabeth II was coronated? The same darn thing: The engravers substituted her portrait for her father’s and before that, her grandfather’s, and the splendid design had another run — right up into the 1960s.

Bechuanaland, page eight: Issues of 1953-60. Guess what happened after 1953, when Elizabeth II was coronated? The same darn thing: The engravers substituted her portrait for her father’s and before that, her grandfather’s, and the splendid design had another run — right up into the 1960s.

Here’s a little oddity (above). In 1960, British imperial powers took it upon themselves to issue this set of stamps congratulating the 75 years of their “protection racket” in Bechuanaland. They must have known by then that their time as colonial masters was rapidly drawing to a close — Ghana already was independent, Sierra Leone and the rest would follow quickly. Yet here we see the Dowager Queen Victoria of 1885, and the demure, fresh-faced Elizabeth of 1960, flanking a scene on the Tswana veld — as though everything were normal as could be, the past and present are of a piece, and the British “protectorate” is secure.

Here’s a little oddity (above). In 1960, British imperial powers took it upon themselves to issue this set of stamps congratulating the 75 years of their “protection racket” in Bechuanaland. They must have known by then that their time as colonial masters was rapidly drawing to a close — Ghana already was independent, Sierra Leone and the rest would follow quickly. Yet here we see the Dowager Queen Victoria of 1885, and the demure, fresh-faced Elizabeth of 1960, flanking a scene on the Tswana veld — as though everything were normal as could be, the past and present are of a piece, and the British “protectorate” is secure.

Bechuanaland, page nine: Issues of 1961. Then bang! came decimal currency, a gift from South Africa. Postal authorities rushed to issue a set with decimal surcharges. When the news reached me, I was excited. These might be rare stamps. I quickly sent off a money order to Lusaka, asking the postmaster to send me a set. Then I sat back and waited … and waited …

Bechuanaland, page nine: Issues of 1961. Then bang! came decimal currency, a gift from South Africa. Postal authorities rushed to issue a set with decimal surcharges. When the news reached me, I was excited. These might be rare stamps. I quickly sent off a money order to Lusaka, asking the postmaster to send me a set. Then I sat back and waited … and waited …

(You may wonder why I still lack to 12 1/2 cent value. Indeed, why not? I recently scanned the online market and couldn’t find it. I’m sure my patience and persistence eventually will be rewarded.)

Bechuanaland, page 10, issues of 1962.

Bechuanaland, page 10, issues of 1962.

Imagine my disappointment when the envelope finally arrived from Bechuanaland Protectorate — with this brand-new set (right) instead of the surcharges. As you might guess, I had to go out on the stamp market and accumulate the surcharged set over a number of years — somehow always missing the 12 1/2 cent value in the process. The set I received from the post office in Lusaka did not include the top value two-rand stamp. I used to think it was because that stamp was issued months later, but now I wonder if I simply didn’t send enough money to cover the whole set. In any case, as you see below, it cost me $11 to buy it and finally complete the 1962 set, which sells online (mint, never hinged) for a decent $75 or more.

Bechuanaland, page 11, issues of 1961-3. More postage due and “omnibus” stamps appear on my last album page for Bechuanaland — though it is not the end of my collection. (Stay tuned for next month’s installment.) Why don’t I have the “Freedom from Hunger” stamp in the middle? Laziness trumps completeness, I guess …

Bechuanaland, page 11, issues of 1961-3. More postage due and “omnibus” stamps appear on my last album page for Bechuanaland — though it is not the end of my collection. (Stay tuned for next month’s installment.) Why don’t I have the “Freedom from Hunger” stamp in the middle? Laziness trumps completeness, I guess …

TO BE CONTINUED

my collection from Natal and St. Helena. You can tell it’s a remainder by the oddly angular postal strike. The catalog value of the St. Helena stamps, in used condition, is in the $100 range. Yet I was able to buy them for under $20. Notice that I added the pencil note “remainders” as a reminder. Last words on the subject: Here is an odd remark from

my collection from Natal and St. Helena. You can tell it’s a remainder by the oddly angular postal strike. The catalog value of the St. Helena stamps, in used condition, is in the $100 range. Yet I was able to buy them for under $20. Notice that I added the pencil note “remainders” as a reminder. Last words on the subject: Here is an odd remark from  the Scott catalogue:

the Scott catalogue:

Good to Be True” blog post,

Good to Be True” blog post,

The closer I looked, the more it appeared to be not a thin, but actually a confetti-like piece of off-white paper, a remnant somehow stuck to the surface of the stamp. i began to pick gingerly at the spot, using my stamp tongs and a magnifying class to keep track of my efforts. Sure enough, the tongs seemed to catch an edge of the

The closer I looked, the more it appeared to be not a thin, but actually a confetti-like piece of off-white paper, a remnant somehow stuck to the surface of the stamp. i began to pick gingerly at the spot, using my stamp tongs and a magnifying class to keep track of my efforts. Sure enough, the tongs seemed to catch an edge of the

This installment of the stamp blog may be a little too esoteric for the general reader —

This installment of the stamp blog may be a little too esoteric for the general reader —

OK. Let’s take a look inside the envelope to see if any of the stamps inside survived this “mishap.”

OK. Let’s take a look inside the envelope to see if any of the stamps inside survived this “mishap.” — waterlogged. The tattered remnants yielded a folded note — the receipt for my order from Du Wei in Shanghai, China — and a stout cardboard packing envelope, securely fastened with tape. A good sign! However, water worries continued. If the stamps had been soaked and ruined, I would be left with nothing from my $30.60 order.

— waterlogged. The tattered remnants yielded a folded note — the receipt for my order from Du Wei in Shanghai, China — and a stout cardboard packing envelope, securely fastened with tape. A good sign! However, water worries continued. If the stamps had been soaked and ruined, I would be left with nothing from my $30.60 order.

Another good sign!

Another good sign!

was due to end in just 15 minutes. To my surprise and puzzlement, there were no other bids. Has this one escaped others’ notice? I would have to think fast. OK, $79 is not a king’s ransom — and look at the prize! The image was a little slanted and out of focus, but I could see no major faults, There was also an image of the back of the stamp, which looked clean. All the perforations seemed in good order. Did the seller not know what he/she was doing? The cancellation did nearly black out the faint lettering of the word “FIVE” — but then again, the clearer letters below spelling “POUNDS” announced a plural denomination, and the set only has a L1 and a L5. This looks like is a great opportunity — a once-in-a-lifetime chance. Better take it. …

was due to end in just 15 minutes. To my surprise and puzzlement, there were no other bids. Has this one escaped others’ notice? I would have to think fast. OK, $79 is not a king’s ransom — and look at the prize! The image was a little slanted and out of focus, but I could see no major faults, There was also an image of the back of the stamp, which looked clean. All the perforations seemed in good order. Did the seller not know what he/she was doing? The cancellation did nearly black out the faint lettering of the word “FIVE” — but then again, the clearer letters below spelling “POUNDS” announced a plural denomination, and the set only has a L1 and a L5. This looks like is a great opportunity — a once-in-a-lifetime chance. Better take it. … I now discovered, with a sinking feeling, the seller’s hometown: Bryansk, Russian Federation. (How often had I been warned against doing philatelic business with the Russians!) Bryansk (I looked it up) is a city of some 415,000 souls located 235 miles southwest of Moscow. I’m sure there are many fine people living there. Probably some gangsters and brigands, hustlers and hackers, too. I just hoped “brikol2” was one of the fine people — one who didn’t know, or care to know, the true value of this item — in which case, I suppose, I would be taking advantage of him/her. Which kind of puts me in the wrong, I guess. Hmmm. Another alternative: The stamp was stolen by a Russian gangster and is now being tossed into the international market place as a piece of hot philately.

I now discovered, with a sinking feeling, the seller’s hometown: Bryansk, Russian Federation. (How often had I been warned against doing philatelic business with the Russians!) Bryansk (I looked it up) is a city of some 415,000 souls located 235 miles southwest of Moscow. I’m sure there are many fine people living there. Probably some gangsters and brigands, hustlers and hackers, too. I just hoped “brikol2” was one of the fine people — one who didn’t know, or care to know, the true value of this item — in which case, I suppose, I would be taking advantage of him/her. Which kind of puts me in the wrong, I guess. Hmmm. Another alternative: The stamp was stolen by a Russian gangster and is now being tossed into the international market place as a piece of hot philately.

for being so suspicious. Just because the seller is a Russian, you jump to all these lugubrious conclusions. How narrow-minded. How provincial. In the morning, you’ll see. Everything will work out. You’ll pay, the stamp will arrive in good time, and it will become a centerpiece of your collection, a remarkable gem amid your estimable Bechuanaland holdings, and a dazzling conversation starter for many a year. Of course, there will always be something of a cloud over the transaction, involving questionable provenance and lack of authentication … Oh well, (yawn) …

for being so suspicious. Just because the seller is a Russian, you jump to all these lugubrious conclusions. How narrow-minded. How provincial. In the morning, you’ll see. Everything will work out. You’ll pay, the stamp will arrive in good time, and it will become a centerpiece of your collection, a remarkable gem amid your estimable Bechuanaland holdings, and a dazzling conversation starter for many a year. Of course, there will always be something of a cloud over the transaction, involving questionable provenance and lack of authentication … Oh well, (yawn) … The Heroes Acre is a landscaped monument and cemetery covering 57 acres just outside Harare, capital city of Zimbabwe. Built as a gift from North Korea to President Robert Mugabe in 1981, it is modeled after a similar memorial near

The Heroes Acre is a landscaped monument and cemetery covering 57 acres just outside Harare, capital city of Zimbabwe. Built as a gift from North Korea to President Robert Mugabe in 1981, it is modeled after a similar memorial near rifles’ magazines. At the center of the cemetery is the Statue of the Unknown Soldier, with three fierce soldiers, including a woman, who look like a cross between Zimbabweans and North Koreans, and who are armed to the teeth with rifles and a grenade launcher.

rifles’ magazines. At the center of the cemetery is the Statue of the Unknown Soldier, with three fierce soldiers, including a woman, who look like a cross between Zimbabweans and North Koreans, and who are armed to the teeth with rifles and a grenade launcher. At first I didn’t connect the stamp

At first I didn’t connect the stamp A medical doctor and founding member of ZANU, Herbert R. Ushewokunze (1933-1995) served in Mugabe’s first cabinet and was a strong supporter of the president, echoing and even overtaking his fellow nationalist in his radicalism, which he laced with rhetorical flourishes and references to Shakespeare. As health minister, he led the campaign to end race-based segregation in health facilities. He accused white doctors and nurses of racism, and pressed for traditional African forms of treatment. Within a year he fell out with Mugabe. He accused the Public Service Commission, which Mugabe used to control the civil service, of still favoring whites, which offended the president. Even worse, he called for an end to nepotism in the commission, which Mugabe was using to reward his loyal followers. So Ushewokunze was sacked without explanation, and spent his final years out of power. Today, Zimbabwe’s health system barely has a pulse. Perhaps Ushewokunze could have done better than his successors; he surely could have done no worse.

A medical doctor and founding member of ZANU, Herbert R. Ushewokunze (1933-1995) served in Mugabe’s first cabinet and was a strong supporter of the president, echoing and even overtaking his fellow nationalist in his radicalism, which he laced with rhetorical flourishes and references to Shakespeare. As health minister, he led the campaign to end race-based segregation in health facilities. He accused white doctors and nurses of racism, and pressed for traditional African forms of treatment. Within a year he fell out with Mugabe. He accused the Public Service Commission, which Mugabe used to control the civil service, of still favoring whites, which offended the president. Even worse, he called for an end to nepotism in the commission, which Mugabe was using to reward his loyal followers. So Ushewokunze was sacked without explanation, and spent his final years out of power. Today, Zimbabwe’s health system barely has a pulse. Perhaps Ushewokunze could have done better than his successors; he surely could have done no worse. Now here is a model hero I’d like to admire. Leopold Takawira (1916-1970) did so well in primary schools in Southern Rhodesia that he went on to become

Now here is a model hero I’d like to admire. Leopold Takawira (1916-1970) did so well in primary schools in Southern Rhodesia that he went on to become By contrast, Nathan Makwirakuwa Shamuyarira (1928-2014) is an exemplar of the kind of rascal Mugabe kept in his inner circle. By the 1950s Shamuyarira had completed his education (with studies at Princeton) and become active in liberation politics, calling for black African self-governance. He showed lots of promise. He was a leader before independence in groups including the Capricorn Society, the group that in the 1950s envisioned an interracial partnership for Zimbabwe. After independence, he joined Mugabe’s cabinet and served

By contrast, Nathan Makwirakuwa Shamuyarira (1928-2014) is an exemplar of the kind of rascal Mugabe kept in his inner circle. By the 1950s Shamuyarira had completed his education (with studies at Princeton) and become active in liberation politics, calling for black African self-governance. He showed lots of promise. He was a leader before independence in groups including the Capricorn Society, the group that in the 1950s envisioned an interracial partnership for Zimbabwe. After independence, he joined Mugabe’s cabinet and served Herbert Wiltshire Tfumaindini Chitepo

Herbert Wiltshire Tfumaindini Chitepo  Grace Mugabe deserves at least a paragraph or two in this mostly uninspiring tale. Not because she is, or was, a Zimbabwe heroine. I don’t think she has been memorialized on a stamp, and she’s not ready for Heroes Acre. Rather she should be known for her audacity, her mendacity, her tenacity and her larceny. Robert Mugabe plucked her from his secretarial pool well before his wife Sally got sick and died. Grace was

Grace Mugabe deserves at least a paragraph or two in this mostly uninspiring tale. Not because she is, or was, a Zimbabwe heroine. I don’t think she has been memorialized on a stamp, and she’s not ready for Heroes Acre. Rather she should be known for her audacity, her mendacity, her tenacity and her larceny. Robert Mugabe plucked her from his secretarial pool well before his wife Sally got sick and died. Grace was Grace Mugabe picked the wrong rival, however, when she took on vice president Emmerson Mnangagwa. I have no idea how he did it, but Mnangagwa managed to outmaneuver the First Lady, and recently was sworn in as Zimbabwe’s second president since 1980. Subsequent reports placed Grace and Robert Mugabe in Singapore. They reportedly have as much as $1 billion in loot stashed in Switzerland and elsewhere.

Grace Mugabe picked the wrong rival, however, when she took on vice president Emmerson Mnangagwa. I have no idea how he did it, but Mnangagwa managed to outmaneuver the First Lady, and recently was sworn in as Zimbabwe’s second president since 1980. Subsequent reports placed Grace and Robert Mugabe in Singapore. They reportedly have as much as $1 billion in loot stashed in Switzerland and elsewhere. One more story: Like many other of his compatriots, Nolan Chipo Makombe (1933-1998) found his way out of his rural region of Masvingo through mission schools. He studied radio and TV technology in South Africa, then taught school, ran a radio shop, and worked for the colonial government as a radio mechanic. He grew active in nationalist politics, and was detained by the colonial rulers in Salisbury for extended periods. After independence he was elected to parliament, representing Masvingo province. He remained a leader in the legislature, eventually serving as speaker of the house. He died of a heart attack in 1998, and was buried in Heroes Acre.

One more story: Like many other of his compatriots, Nolan Chipo Makombe (1933-1998) found his way out of his rural region of Masvingo through mission schools. He studied radio and TV technology in South Africa, then taught school, ran a radio shop, and worked for the colonial government as a radio mechanic. He grew active in nationalist politics, and was detained by the colonial rulers in Salisbury for extended periods. After independence he was elected to parliament, representing Masvingo province. He remained a leader in the legislature, eventually serving as speaker of the house. He died of a heart attack in 1998, and was buried in Heroes Acre. Before I end this sorry history and dismal speculation, let me sound a clarion call from the past. It involves a white, English-born patrician named Arthur Guy Clutton-Brock. His story provides a poignant coda

Before I end this sorry history and dismal speculation, let me sound a clarion call from the past. It involves a white, English-born patrician named Arthur Guy Clutton-Brock. His story provides a poignant coda This essay is about stamps, I promise you. Or at least it includes stamps. When you set to writing about Zimbabwe, however, you have to start with Robert Mugabe.

This essay is about stamps, I promise you. Or at least it includes stamps. When you set to writing about Zimbabwe, however, you have to start with Robert Mugabe. not enough to buy a loaf of bread, so six months later came a $100 trillion bank note, The currency soon collapsed;

not enough to buy a loaf of bread, so six months later came a $100 trillion bank note, The currency soon collapsed; whatever work force there is makes up an

whatever work force there is makes up an

Earlier this year, according to Australian site

Earlier this year, according to Australian site

Don’t look here for a detailed sketch of Robert Mugabe or his former rival, Joshua Nkomo. Their stories are well-known. In Mugabe’s case, the story is one that will leave a mark of infamy for the ages.

Don’t look here for a detailed sketch of Robert Mugabe or his former rival, Joshua Nkomo. Their stories are well-known. In Mugabe’s case, the story is one that will leave a mark of infamy for the ages.  Nkomo, the hapless representative of the Ndebele minority tribe, plays only a minor role in the drama. He gave up his opposition role and joined Mugabe’s corrupt regime as a minor partner. I don’t know if he managed to siphon off any of the millions flowing into Mugabe’s accounts over the years. He made his pact, sold his soul, and probably should have cashed in. In which case, he ended up being just another rascal.

Nkomo, the hapless representative of the Ndebele minority tribe, plays only a minor role in the drama. He gave up his opposition role and joined Mugabe’s corrupt regime as a minor partner. I don’t know if he managed to siphon off any of the millions flowing into Mugabe’s accounts over the years. He made his pact, sold his soul, and probably should have cashed in. In which case, he ended up being just another rascal.

While working to build my collection of British Somaliland stamps, I came across a previously unknown-to-me

While working to build my collection of British Somaliland stamps, I came across a previously unknown-to-me

million pounds. Britain’s main concern from the outset was quelling the Dervish uprising — a latter-day incarnation of today’s Islamic State or Taliban. Once the insurgents were

million pounds. Britain’s main concern from the outset was quelling the Dervish uprising — a latter-day incarnation of today’s Islamic State or Taliban. Once the insurgents were

decisively routed in 1920, after a daring aerial attack on

decisively routed in 1920, after a daring aerial attack on Somaliland continued as a sleepy, largely barren outpost

Somaliland continued as a sleepy, largely barren outpost

philatelic scholar explains: “Postage stamps continued to be produced illegally internationally during the war, although their subject matter suggests they were designed for external collectors.” (For more on this distressing phenomenon of stamp mills producing fodder for topical collectors with no real connection to the nominal country of issue, see FMF Stamp Project blog posts of February 2018, “Cinderellas: A Spreading Stain”; and March 2018,

philatelic scholar explains: “Postage stamps continued to be produced illegally internationally during the war, although their subject matter suggests they were designed for external collectors.” (For more on this distressing phenomenon of stamp mills producing fodder for topical collectors with no real connection to the nominal country of issue, see FMF Stamp Project blog posts of February 2018, “Cinderellas: A Spreading Stain”; and March 2018,  Before I close, a word or two (or more) on the postal history accompanying this civic narrative. The first postage stamps from the Horn of Africa were the British

Before I close, a word or two (or more) on the postal history accompanying this civic narrative. The first postage stamps from the Horn of Africa were the British  India overprints that began in the 1880s. Italian authorities came out with stamps from “Benadir” starting

India overprints that began in the 1880s. Italian authorities came out with stamps from “Benadir” starting  in 1903, then “Oltre Guiba” (Jubaland) in the 1920s, then simply Somalia or Italian Somaliland. The neighboring French started issuing stamps from “Obock” in the 1890s, then the

in 1903, then “Oltre Guiba” (Jubaland) in the 1920s, then simply Somalia or Italian Somaliland. The neighboring French started issuing stamps from “Obock” in the 1890s, then the  French Somali Coast (Cote Francaise des Somalis) after the turn of the century. In the 1960s it was renamed the French Overseas Territory of Afar and Issas, before becoming independent Djibouti in 1977.

French Somali Coast (Cote Francaise des Somalis) after the turn of the century. In the 1960s it was renamed the French Overseas Territory of Afar and Issas, before becoming independent Djibouti in 1977.  And so the nations come and go. Sic transit gloria — except that in the Horn of Africa, there wasn’t much glory in the region’s imperial past, and there seems to be very little to celebrate in the struggles of today. But speaking of Afar and Issas and stamps, I must

And so the nations come and go. Sic transit gloria — except that in the Horn of Africa, there wasn’t much glory in the region’s imperial past, and there seems to be very little to celebrate in the struggles of today. But speaking of Afar and Issas and stamps, I must  say that nation issued some ravishing, over-size, multicolor engravings.

say that nation issued some ravishing, over-size, multicolor engravings.

Here are some more stamps from British Somaliland. While King Edward VII was on the throne (1902-11), the area was declared a protectorate. It remained that way through the reigns of George V and George VI (see stamp at right), then on to Elizabeth II and independence in 1960.

Here are some more stamps from British Somaliland. While King Edward VII was on the throne (1902-11), the area was declared a protectorate. It remained that way through the reigns of George V and George VI (see stamp at right), then on to Elizabeth II and independence in 1960.

Philately from Italian Somaliland began humbly enough, with overprints of stamps from the motherland. (right)

Philately from Italian Somaliland began humbly enough, with overprints of stamps from the motherland. (right)

Herewith a running commentary on the stamps as they arrive.

Herewith a running commentary on the stamps as they arrive.

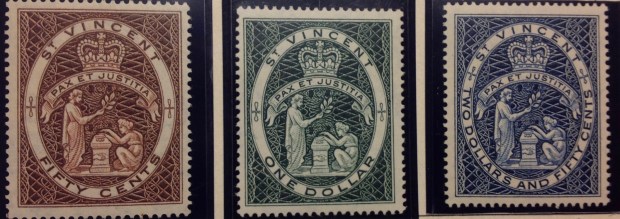

The Seal also appears in these next stamps, from the Edwardian era. There are three distinct “sets” using this design, which differ in such details as the inscription on tablets below the figures — and whether or not there is a “dot” in the numeral lozenge. Some of these stamps are quite costly. I paid a few bucks for the ones pictured here.

The Seal also appears in these next stamps, from the Edwardian era. There are three distinct “sets” using this design, which differ in such details as the inscription on tablets below the figures — and whether or not there is a “dot” in the numeral lozenge. Some of these stamps are quite costly. I paid a few bucks for the ones pictured here. These George V definitives are from two long sets that differ only in watermark: One set has a “multiple crown and CA” (for Crown Agents) watermark; the other carries the “script crown and CA” watermark. Ah, watermarks! The bane of my existence (along with perforations), which I suppose I shall have to write about sometime …

These George V definitives are from two long sets that differ only in watermark: One set has a “multiple crown and CA” (for Crown Agents) watermark; the other carries the “script crown and CA” watermark. Ah, watermarks! The bane of my existence (along with perforations), which I suppose I shall have to write about sometime … Here is also a pretty 1-cent definitive from the George VI decimal series. It only cost me a dime, and it fills one of the few remaining holes in a long set that, when complete, will be spectacular!

Here is also a pretty 1-cent definitive from the George VI decimal series. It only cost me a dime, and it fills one of the few remaining holes in a long set that, when complete, will be spectacular! First, notice the envelope from Arizona. Somehow, a 10-centime stamp from French Guiana in the 1940s is stuck next to a standard “forever” stamp honoring the bicentennial

First, notice the envelope from Arizona. Somehow, a 10-centime stamp from French Guiana in the 1940s is stuck next to a standard “forever” stamp honoring the bicentennial

Now, here’s a coincidence. Take a look at the second envelope that arrived today. It presents a small array of common U.S. postage stamps of the recent past, a

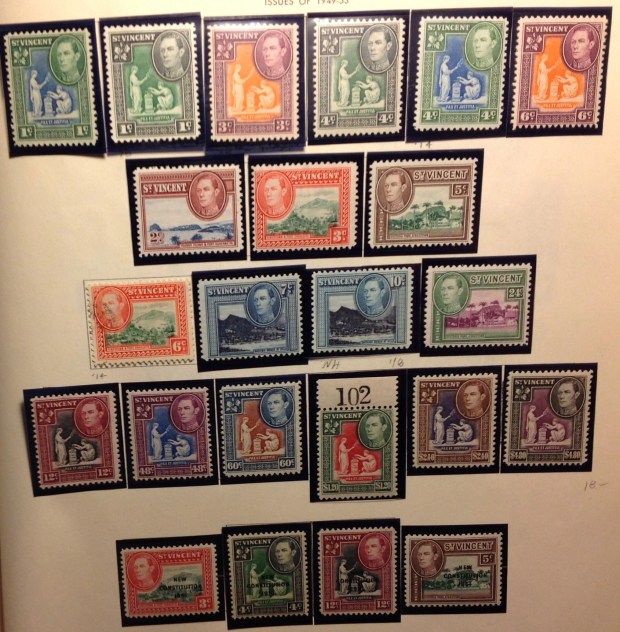

Now, here’s a coincidence. Take a look at the second envelope that arrived today. It presents a small array of common U.S. postage stamps of the recent past, a As you will notice on the stockcard (right), where I have arranged them temporarily, this new batch of St. Vincent stamps includes definitives from the reigns of Edward VII, George V and George VI.

As you will notice on the stockcard (right), where I have arranged them temporarily, this new batch of St. Vincent stamps includes definitives from the reigns of Edward VII, George V and George VI.

Last loose-end tie-up:

Last loose-end tie-up:

cards and letters

cards and letters Way to go! In following days, I received a delightful philatelic cascade of seven envelopes. As it happened, each letter was from a different state: Virginia, Washington, Tennessee, Ohio, Arizona, Illinois and Nevada. This was pure coincidence — I was not trying to set a record for sellers in different states, just trying to fill out my Bechuanaland and Somaliland collections. What does this diversity suggest? For one thing, that stamp-collecting is deeply embedded in the U.S. heartland. At least, a lot of folks with stamps they want to sell are living all over the country. Maybe they are selling off their stamp collections, or just having fun in retirement. Maybe some of them are still collecting — selling some stamps and buying others. I received this poignant note from one seller: “Fred, Thank you for your order. Please keep checking. Every stamp I sell from my collection helps my family buy things we need to get by. May God bless you, Gregory.”

Way to go! In following days, I received a delightful philatelic cascade of seven envelopes. As it happened, each letter was from a different state: Virginia, Washington, Tennessee, Ohio, Arizona, Illinois and Nevada. This was pure coincidence — I was not trying to set a record for sellers in different states, just trying to fill out my Bechuanaland and Somaliland collections. What does this diversity suggest? For one thing, that stamp-collecting is deeply embedded in the U.S. heartland. At least, a lot of folks with stamps they want to sell are living all over the country. Maybe they are selling off their stamp collections, or just having fun in retirement. Maybe some of them are still collecting — selling some stamps and buying others. I received this poignant note from one seller: “Fred, Thank you for your order. Please keep checking. Every stamp I sell from my collection helps my family buy things we need to get by. May God bless you, Gregory.” Here’s how I handle my cache of new lots. First I slice the envelopes with my letter-opener, draw out the contents, spread them out on my desk and admire the resulting philatelic clutter. I harvest the colorful stamps the sellers pasted on the envelopes for postage, and stash them in the large envelope I use for such accumulations.

Here’s how I handle my cache of new lots. First I slice the envelopes with my letter-opener, draw out the contents, spread them out on my desk and admire the resulting philatelic clutter. I harvest the colorful stamps the sellers pasted on the envelopes for postage, and stash them in the large envelope I use for such accumulations.

That’s how my latest buying binge started. I spotted a long-desired stamp — the 5 shilling from the first (and only) Queen Elizabeth set of Somaliland Protectorate, a small territory formerly under British supervision in the Horn of Africa. It’s a charming little stamp, a two-color engraving, emerald green and brown, issued in 1953. The young queen’s portrait sits next to a delicately etched Martial Eagle perched on a promontory in a rocky landscape. I recently acquired the 10 shilling of the set, and lacked only this stamp to complete my series. But the stamp is not cheap — prices on the Internet range upward from $11 to $28 for a mint copy. So when I noticed it in a “sale” email, going for $9.50, it got my attention. Not only that: The seller added to his pitch the phrase “…or best offer.” Plus, shipping was free. I shaved 50 cents off the asking price and submitted my offer for $9, which was promptly accepted. (How low should I have gone?) Hooray! My set would be complete.

That’s how my latest buying binge started. I spotted a long-desired stamp — the 5 shilling from the first (and only) Queen Elizabeth set of Somaliland Protectorate, a small territory formerly under British supervision in the Horn of Africa. It’s a charming little stamp, a two-color engraving, emerald green and brown, issued in 1953. The young queen’s portrait sits next to a delicately etched Martial Eagle perched on a promontory in a rocky landscape. I recently acquired the 10 shilling of the set, and lacked only this stamp to complete my series. But the stamp is not cheap — prices on the Internet range upward from $11 to $28 for a mint copy. So when I noticed it in a “sale” email, going for $9.50, it got my attention. Not only that: The seller added to his pitch the phrase “…or best offer.” Plus, shipping was free. I shaved 50 cents off the asking price and submitted my offer for $9, which was promptly accepted. (How low should I have gone?) Hooray! My set would be complete.