Griqualand West!

A semi-nomadic tribe, neither Brit nor Boer, black nor white, ruled the veld and river valleys of the Cape Colony’s northwestern frontier — until its homeland became a diamond field.

Annexed by Great Britain: 1871

First stamps: 1874

Busiest stamp-issuing years: 1877-8

Joined Cape Colony: 1880.

In 1867, the first diamond in southern Africa was recovered from the veld and river diggings in Griqualand. Among the stones was one weighing in at 21 1⁄2 carats — the Eureka Diamond. Although the excited prospectors in Colesberg tried to keep it quiet, the news immediately leaked to the Advertiser, which rushed into print the same day with this breathless account:

“THE WONDERFUL SOUTH AFRICAN DIAMOND

There is a story this morning afoot in the village. It has just been told us by a lady and we give it just as we have heard it. A Mr. John O’Reilly, a hunter, explorer etc., something of the Dr. Livingstone stamp but not quite so well known, in his travels in the North Country -– somewhere about the Orange River -– picked up a stone two or three months since which he thought had something remarkable about it and brought it down with him. It was shown to several persons here and was at length sent to Dr. Atherstone in Graham’s Town to be examined and, as the lady told us, a letter has come by this morning’s post from the doctor saying it is a diamond and worth £800. Now we quite expect the Great Eastern (ED: A rival newspaper) will have a great laugh at us about the South African Diamond as he did some time ago about the Orange River Serpent but we have stated the report just as we have heard it. Stranger things have come to pass in the world than the Discovery of Diamonds in South Africa.”

A pudding-shaped hill 20 km from the Vaal River became the boom town of Kimberley. Diggers streamed in from all over, and the diamond mine grew to be the biggest hole in the world. The Colonial secretary, addressing the Cape House of Assembly, said: “Gentlemen, on this rock the future success of South Africa will be built.” He was right, in that diamonds and other minerals have made fortunes, enriched many, provided employment and tax revenues and indeed helped to build a booming t economy; unjust, unfair, racist for more than a century; yet South Africa, for the most part, has been a money-maker.

Isn’t it about time I got around to stamps? Well, there weren’t any to talk about in this part of southern Africa. Everyone basically used stamps from the Cape of Good Hope. Depending on what far-flung outpost you inhabited, you might find stamps at the post office from the ZAR (South African Republic), or the Orange Free State, both of which started issuing their own sets in the late 1860s. Every conceivable stakeholder made territorial claims to the diamond fields — the Brits, and Boers from the Cape Colony, Orange Free State and Transvaal, as well as Griqua leader Nicolaas Waterboer — though none of them bothered to consider the rights of the aboriginal Black people who were living there to begin with.

Amid the jousting between Boers and Brits, uitlanders, Afrikaners and others, Griqualand threatened to become Africa’s “wild west.” I promise to get to stamps shortly, but first I must pause to explore at greater length what “Griqualand West” means. Why “west”? Is there a Griqualand “east”? And what does Griqua mean anyway?

So many questions! One at a time …

Griqualand West was a large territory on the Cape Colony’s northern border. It was home to the Griqua people, a semi-nomadic group that occupies a unique niche in south African history and demography. This

population is descended from Boer settlers of the 1600s. With few caucasians available, strapping young Boers settled down with indigenous women, mostly from the Khoikhoi tribe, but also Tswana, San,

Xhosa and others, including Bushmen (Bushwomen?). Their children were raised speaking Dutch, distinct from their indigenous cohort. The mixed-race offspring intermarried, traditions were passed down, and a population emerged that was neither Boer nor Bantu, neither white nor black — a tribe of its own, named Griqua after a Khoi ancestor. Much later, under South Africa’s apartheid regime, the Griqua were classified as “coloured,” to distinguish them from both whites and blacks.

In the crude parlance of the early days, the Griquas were first labeled Bastaards, though the authorities eventually promoted more dignified terms like Korana, Oorlam, or Basters. Trained horsemen, many Basters earned their living and reputations by serving the Cape Colony as commandos against Khoi and San adversaries. Eventually, Griquas chafing under Boer bigotry and British imperialism migrated into the border lands. The story of Griqualand went on, including tensions between leaders and a migration in the 1860s that has been called one of the great epics of African

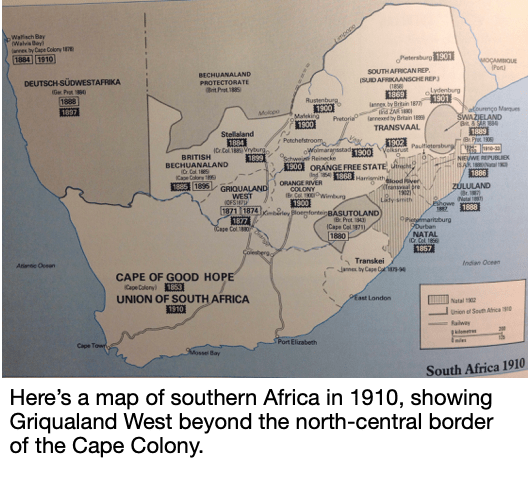

history, though it is little noted in these parts. The survivors settled in land offered by Natal far to the east — Griqualand East (see map). Depleted by their travails, these Griquas restored their herds and other resources, and managed their semi-nomadic affairs in this new homeland.

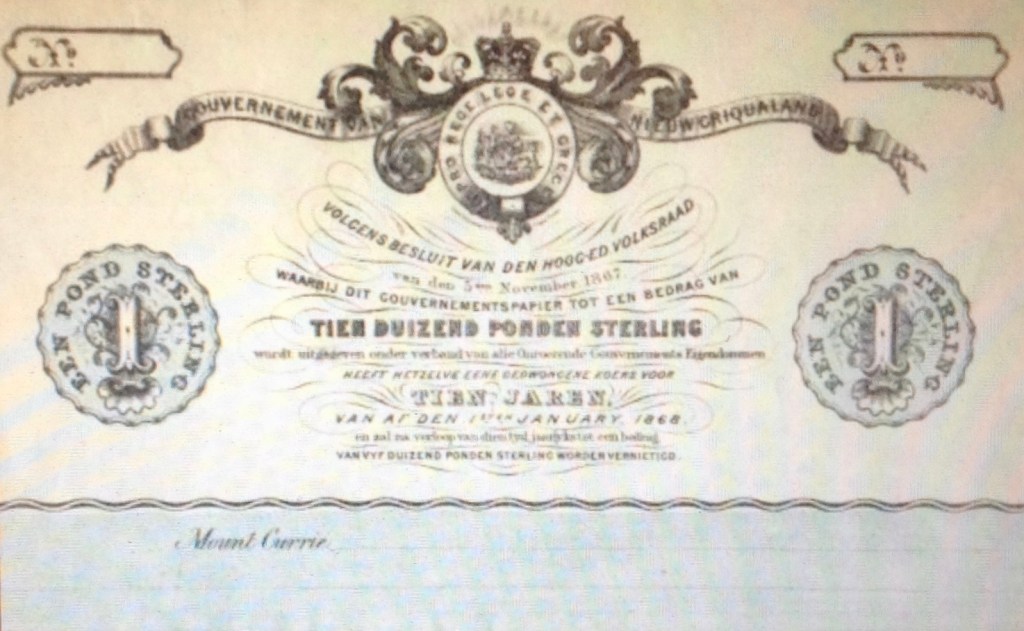

While Griqualand East never issued stamps, it did produce a supply of one-pound bank notes — which were never officially issued, and ultimately destroyed. (You may be able to find a rare example, but it likely will cost thousands. The image below is from the Internet.) By 1874, the Griquas had decided to throw in with the British, and Griqualand East was annexed by the Cape Colony.

Just a word about some of the Griqua personalities involved. Among the most notable elites were the Koks and the Waterboers. Andries Waterboer (c.1789—1852) was a descendant of Bushmen, described as “fiercely ambitious.” He prevailed over rivals

and maintained his territory from all comers, passing on leadership to his son Nicolaas when he died in 1852.

Adam Kok was the original “Kaptein” or ruler of Griqualand, but his heirs were displaced by the Waterboers. Adam Kok II moved east from original Griqua lands, presiding over a region called Philippas (a/k/a/ Adam Kok’s Land). The

last migration took place under Adam Kok III. Starting in 1861, the Griquas crossed the Drakensberg mountain range, at great cost, finally reaching their destination, south of Natal, called Nomansland (I kid you not).

In ensuing years, the Waterboer regime to the west enlisted the services of David Arnot, a Griqua and Cape-trained lawyer. Handsome and impeccably dressed, the biracial agent proved instrumental in protecting the interests of the Griquas. One biographical database describes him as “emotional, ostentatious, unscrupulous and highly intelligent.” He is credited with

successfully navigating the Griquas toward a safe harbor with the British and away from the covetous Boers of Transvaal and the Orange Free State. Arnot was said to favor the British over the Boers, despite his ancestry. Incidentally, he was a noted botanist and naturalist. Four desert succulents are named for him, along with a land snail

and a bird, Arnot’s Chat (Myrmecocichla arnoti).

By 1870, numerous sides in and around the diamond fields of Griqualand West were appealing for Queen

Victoria’s protection. Amid the lawlessness and disorder, a foppish artist and miner named Stafford Parker stepped forward to proclaim a “diggers state,” which he dubbed the Klipdrift Republic. No stamps, as far

as I know, though he did have a flag, in keeping with the heraldic passions of the times. President Parker made modest-sized plots available to diggers — as long as they were white-only. The republic was in business for several months, until the British arrived in Kimberley, at which time President Parker and his cabinet promptly resigned.

The British finally took charge in Griqualand West in 1871. Somehow, the region had gone deeply into debt, despite the diamonds sparking in the veld. Bad weather, drought, the failure of crops had something to do with it. Then there was all the unrest and conflict over land and diamonds.

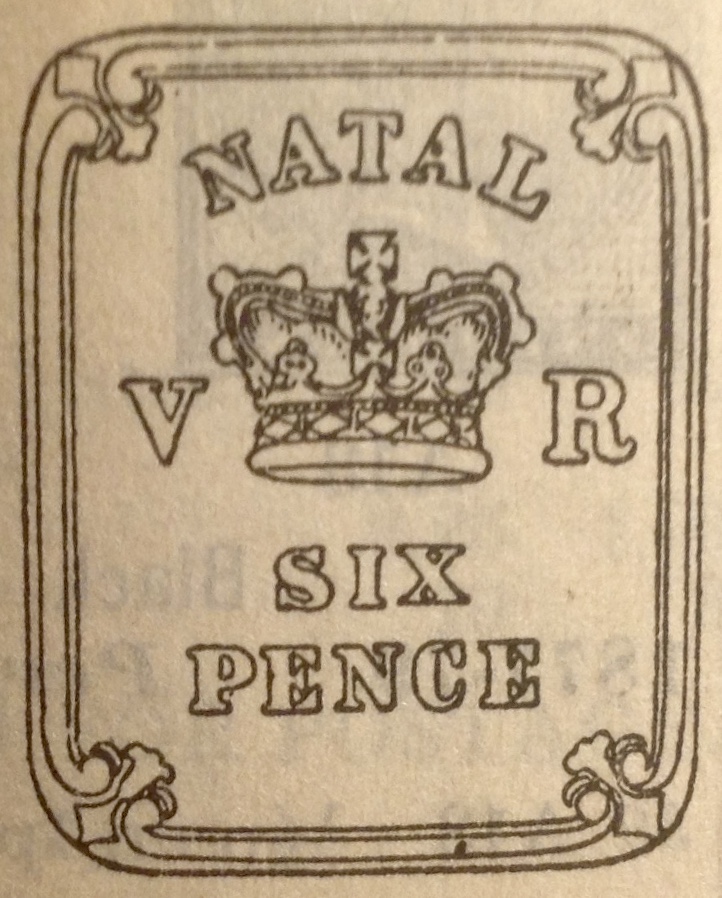

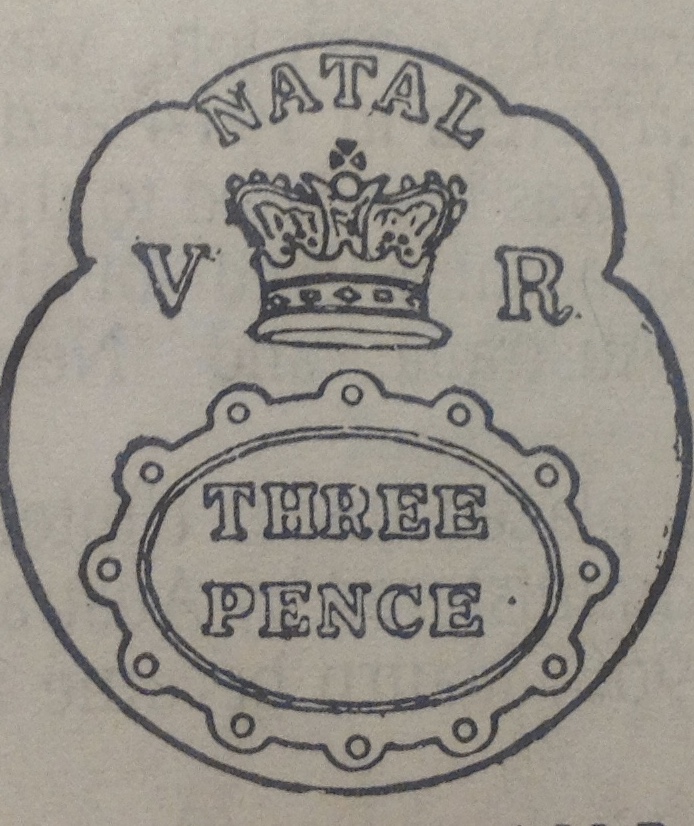

Now, at last, stamps began to appear that were specially designated for use in the new “province” or colony of Griqualand West. Griqualand East under Adam Kok III went its own way, using stamps of Natal or the Cape of Good Hope until it joined the Cape Colony in 1874. Griqualand West was annexed in 1880, thanks in part to the efforts of that skilled attorney/naturalist David Arnot, who held off the Boers and won a legal judgment for his Griqua boss, Nicholaas Waterboer. In 1871, Waterboer placed his Griqua territory under the protection of the British, and in the following years the busy colony became a stamp-issuing country.

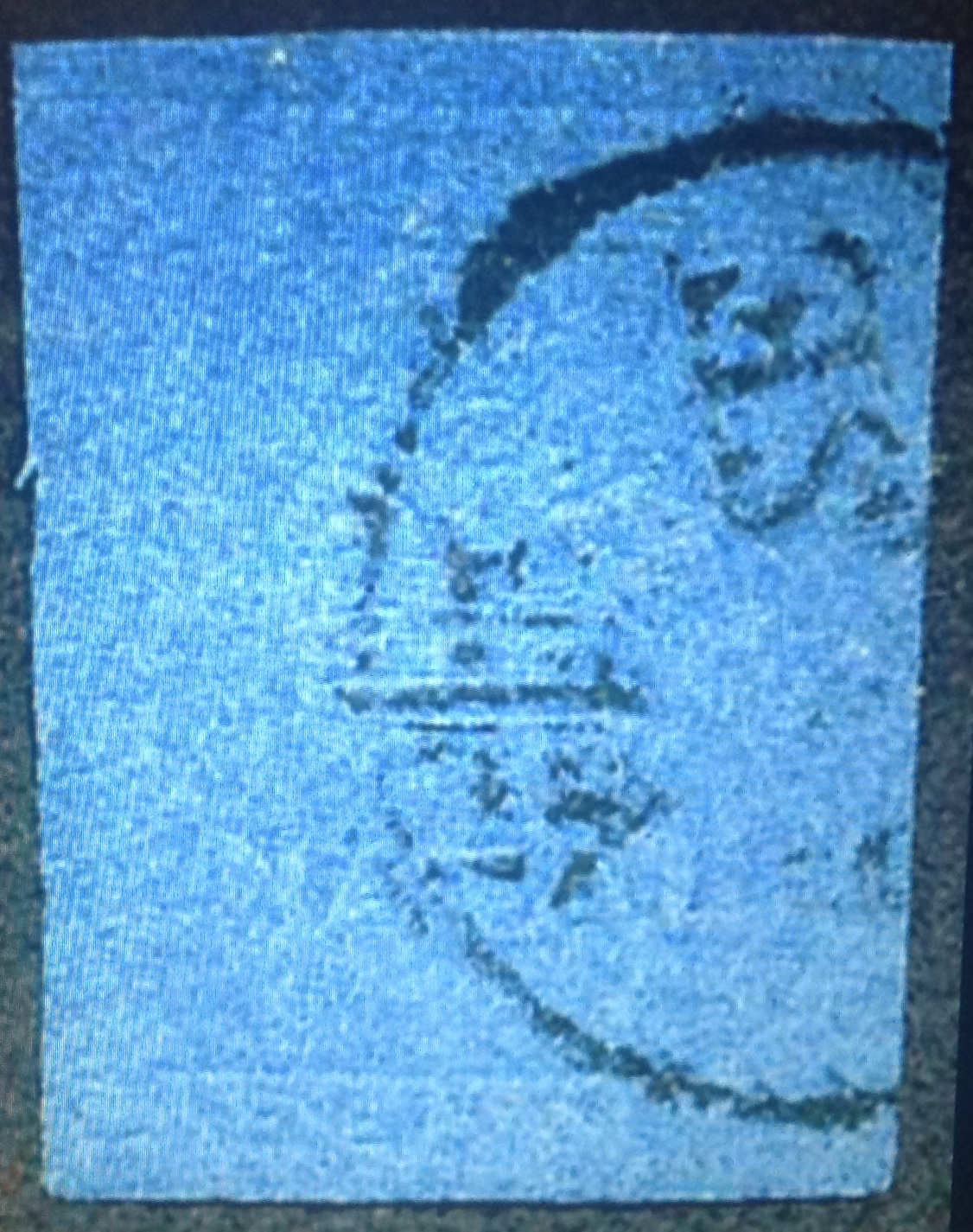

During a two-year span, 1877-78, Griqualand West made use of a variety of overprints, always using Cape of Good Hope stamps. The Scott catalogue has more than 100 entries, nearly all of the stamps bearing the single

overprinted letter “G.” All except No. 1 (1874), which is a scrawled “1d” surcharge and very pricey; and Nos. 2 and 3 1877), which are overprinted “G.W.” (Griqualand West, get it?) They also are expensive (you get the idea from the empty spaces in my album, above) .

Let me interject: Griqualand West did issue more than just overprinted Cape of Good Hope stamps. There are official labels inscribed “Province of Griqualand West.” But they are revenue stamps, not valid for mail and thus off the radar for postage stamp collectors like me. I include below examples (from the Internet) of the set issued in 1879, just to share their exquisite design: a fine (and flattering!) side portrait of the mature Queen Victoria, in a circular border with a belted frame, a crown above and floral fans in the corners. I pause to speculate: Why design and issue original revenue labels, but not original postage stamps? Could it be because there was less letter-writing than revenue-sharing going on in the diamond fields of Griqualand West? (By the way, these stamps aren’t cheap — apparently people do collect revenue stamps!)

An idle question also occurs: Why did the overprints change from “G.W.” on the two early stamps, to just “G” on the rest? I suppose the answer is that by 1877, Griqualand East had ceased to exist, having merged with the Cape Colony, so the authorities realized that Griqualand West was the only “Griqualand” left — hence the “G” stands alone.

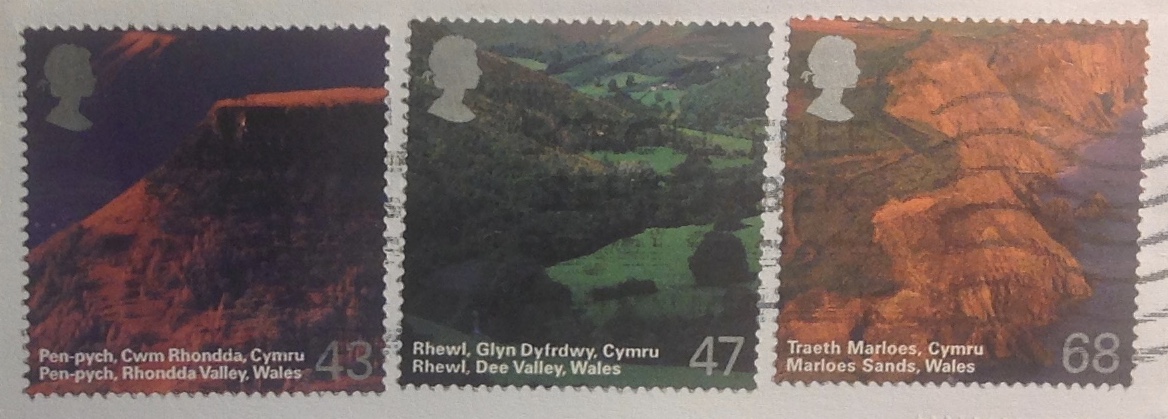

As for all those “G” overprints, some are not costly or hard to get. I picked up six so far for my collection through Internet purchases, most of them for under $10 (see illustrations below).

In stamp after stamp, the allegorical figure of Hope is resting by her anchor, while the letter “G” dances and sparkles somewhere on the stamp — a rounded capital, thin or thick, narrow or angled, in black, red or blue, like a diamond in the rough.

ADDENDUM:

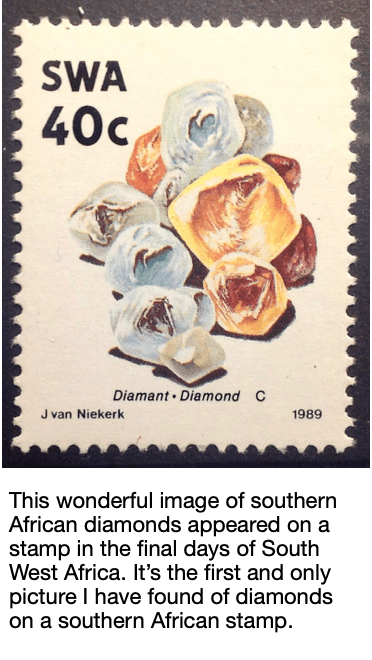

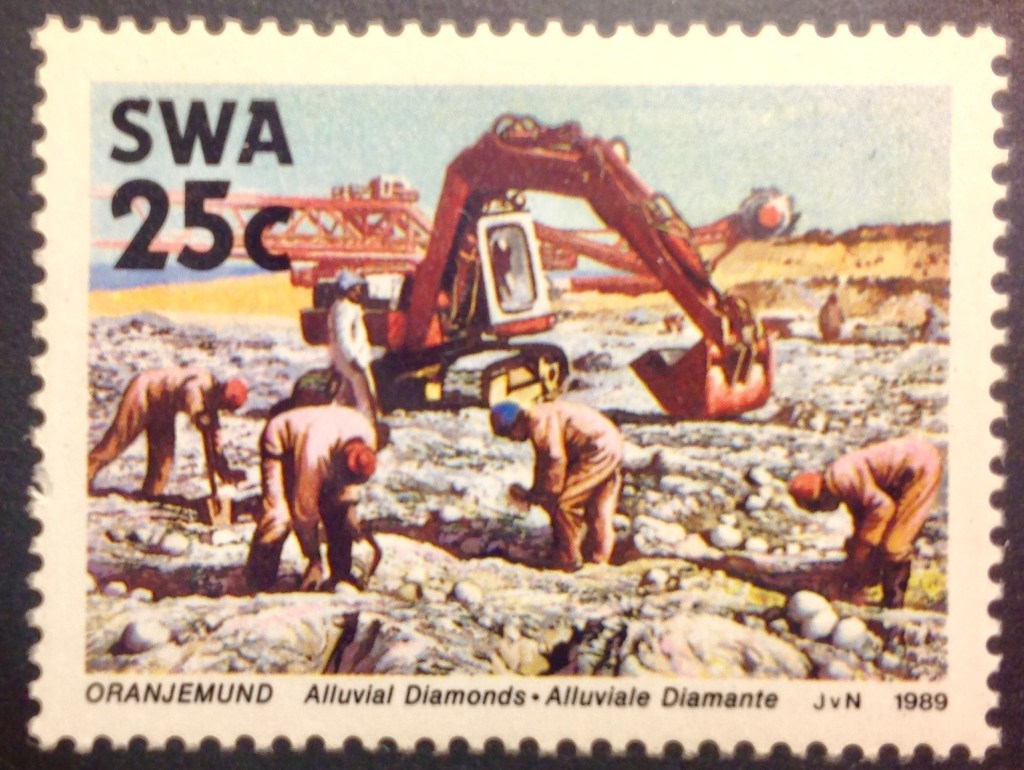

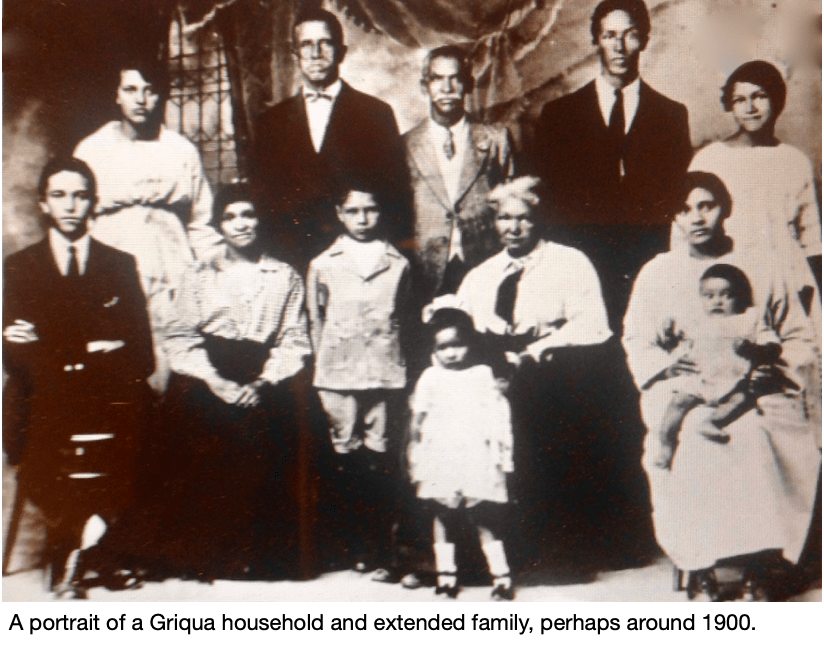

This has nothing to do with stamps, but rather with the meaning of Griqua. I include some images from the web depicting “basters,” or mixed-race South Africans descended from unions between Boer settlers and Khoi, San, or other tribal partners. I found it fascinating to study the faces in Griqua images from the Internet, It’s fun to try and identify features that might go back to a Dutch ancestor, or a Bushman; a Boer, Khoi, San — or an Englishman. Many of these Griquas today are settled in Namibia. My essay dealt with the Griqua dynasties of the Koks and Waterboers in the 1800s, in territory that today is

part of South Africa. Remember how David Arnot, the anglophile Griqua lawyer, helped arrange for Great Britain to “protect” Griqualand West from the Boers? Did he really do the Griquas a favor by joining with the Cape Colony? For a while there was a nonracial “qualified franchise” that would have allowed land-owning Griquas to vote. But after the Boers and Brits joined forces in the Union of South Africa in 1910, the Griquas became subjects of the new, racist state. Under apartheid, they were marked “coloureds” and denied civil rights. The die was cast by 1894, when David Arnot died in Cape Town, age 74. His death was little noted in the press, even the Advertiser in Colesberg, the diamond-mining town he had served in many capacities. A local historian concluded with some ambivalence: “Thus died a man who fundamentally altered the course of history and in his person, compounded his country’s problems and its aspirations.”

Although denied full civil and political rights in pre-1994 South Africa, the Griqua people apparently were fruitful and multiplied. The “coloured” population of South Africa today calls attention to the fact that “race” is an arbitrary human construct, but even more so, “racism.”

TO BE CONTINUED

Orange Free State!

First Issue: 1868

Is anyone else tiring of my lengthy, meandering trek through the postal history of southern, central and east British Africa? Is it starting to feel like a slog, after three essays on ZAR/Transvaal? Although I count 21 separate stamp-issuing authorities between 1857 (Cape of Good Hope) and Basutoland (1933), I am certain I can cover the territory in just a few more chapters, combining postal upstarts like Stellaland, Griqualand West and the New Republic. In any case, I shall feel free to divert from this expedition, should another interesting topic draw the attention of the FMF Stamp Project.

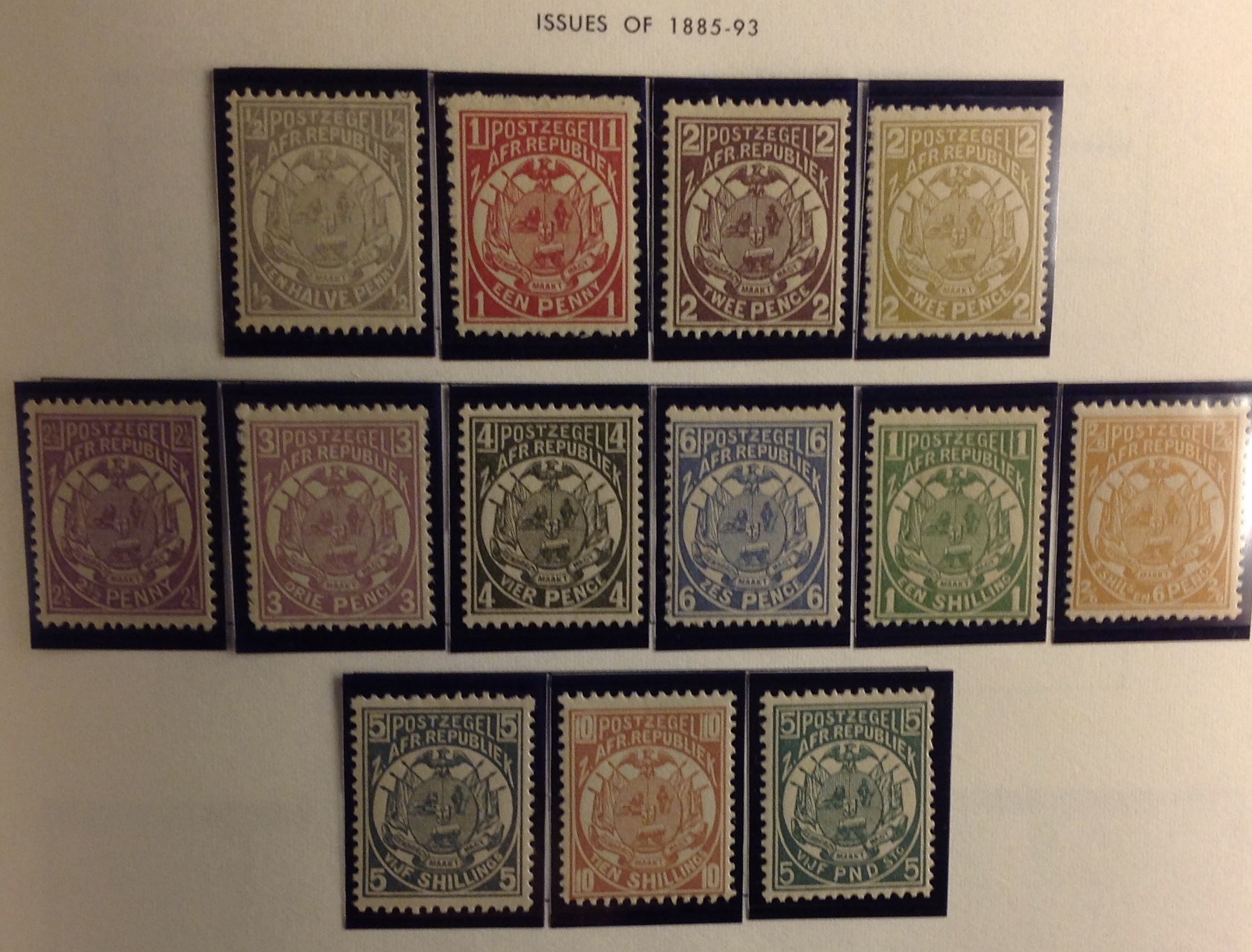

I’ve traced the postal path from the first colonial stamps of southern Africa— the Cape of Good Hope triangles (1857) — onward, through hundreds of pages (profusely illustrated, to be sure), and we’ve only reached 1868. Well, riveting stories had to be told, and some of the stamps are downright cute, remarkable, certainly puzzling, even valuable! Of course, other stamps are quite dull — like those ZAR/Transvaal sets, all bearing the busy Boer coat of arms, varying only by size and rendering, color, printing quality, denomination and whether the occupying British had managed to stamp Queen Victoria’s initials on them. (Not to mention the counterfeiting conundrum.) OK, so they’re boring — which only makes the other stamps more interesting, right?

Wrong. The Orange Free State’s stamps are even duller than those of ZAR/Transvaal. At least the Boers across the Vaal River (Trans-Vaal, get it?) redesigned their coat-of-arms stamps over the years; they even issued one commemorative in 1896. Both ZAR/Transvaal and the Orange Free State began issuing its stamps at about the same time. But the smaller Boer republic to the south chose one design — an orange tree, the “tree of freedom” — and stuck with it for 32 years. (As an aside, this habit of keeping the same design going for years remained popular in the Union of South Africa after 1910. A definitive set first issued in 1926 went through several minor updates and printings, with the final stamps issued in 1954 — 28 years later.)

A word about that orange tree. Kind of makes you think the Orange Free State was named after the fruit, doesn’t it? Wrong. Tricked by a stamp! The name actually comes from the south African river Orange, named for the royal family of Holland, Valhalla of Boer legend. Incidentally, the coat of arms of the Orange Free State (left), similar to the badge of the House of Orange, includes bugle horns around a tree, like the stamp; NOT an orange tree. but a small tree with planed branches, like a cedar. On the stamp, however, there’s no doubt it’s an orange tree. For one thing, the Scott catalogue describes the design as “Orange tree.” For another, after the Boers and Brits formed the union of South Africa, the 6d definitive stamp featured the same orange tree — this one with full-color fruits. (see below)

Do you really want me to run through the long boring history of the Orange Free State? Well, maybe not so boring, but not that interesting to this stamp collector, anyway. There was lots of conflict — between Boers and Basothos, Boers and Brits, also occasional unease between the two neighboring Boer republics — Orange Free State and Transvaal/ZAR. After the British imperialists and Boer settlers reached their various agreements, they went their respective ways and pretty much prospered — that is, until they came to blows again. The discovery of diamonds in the rocky reefs of the high tableland contributed to the state’s fortunes — and tensions. The self-governing Orange Free State lasted from 1854 to 1902 — quite a record. A number of state presidents presided, of varying abilities. One of them was the son of Boer hero Andres Pretorius. Marthinus had the misfortune to have the Transvaal/ZAR capital city of Pretoria named after his dad. It was a tough act to follow, and he bombed. The guy who really pulled things together was Johannes Brand, who presided for a remarkable 24 years, during which he continued to be re-elected and achieved satisfactory economic growth. I have not made a close study of him. What I do now is that he seemed perfectly content to keep issuing the same set of stamps, over and over, year after year …

Over the years the Orange Free State and Transvaal/ZAR existed in harmony — most of the time. There were continuing efforts to unite them into a singular, powerful Boer republic to stand up to the Brits in Natal and the Cape Colony. The ZAR’s Paul Kruger was a Boer chauvinist who mistrusted the British. (Kruger created an international scandal in 1897 when he called Queen Victoria a kwaage Vrou — angry woman.) Orange Free Staters tended to be less anti-British — though by the time the test came in October 1899 with the Second Boer War, the two states were allied by treaty to do battle together. British Lord Roberts occupied Bloemfontein and claimed victory within four months, but Orange Free State Boers fought on — with the Volksraad meeting in the field as needed — until the Treaty of Vereniging was signed May 31, 1902. During the interval between the British annexation claim in 1900 and the signing in 1902, two parallel governments were operating, with occasional hostilities breaking out. It must have been a nightmare for the inhabitants, black and white; no to mention there were two sets of orange-tree stamps in circulation, one overprinted “V.R.I,” one not. Confound it!

At first, the stamps issued under British occupation were no more interesting than the original Orange Tree set. The Brits simply added the overprint V.R.I. which stands for Victoria Regina Imperatrix — Victoria Queen Empress. Cute. The Scott catalogue lists two distinct sets of overprints, based on whether the periods between the initials are “Level with Bottoms of Letters” or “Raised Above Bottoms of Letters.” The set with “level” periods is scarcer than the set with “raised” periods, but it’s tricky. The catalogue lists many varieties, including “No period after V” … “Missed periods” … “Pair, one with level periods” … “Thick V” … You could spend a small fortune, accumulating a collection of these boring stamps and varieties. If you put the whole thing together, and explained it, would it be less boring?

With the official launch of the Orange River Colony in 1902, postal authorities issued a n original, country-specific set, bearing a portrait of the new monarch, the late Victoria’s elderly son and heir, Edward VII. The small stamps were intricately designed with a springbok on one side and a wildebeest on the other. (I think I have those animals right.)

The stamps printed in two colors are attractive enough, if a bit garish. In any case, there wasn’t much time to complain: In 1910, South Africa took over.

Back in 1902, as Viscount Milner assumed the post of governor of the Orange River Colony, he gathered around him the ablest of the executive and consular service, including Marthinus Steyn and Christiaan de Wet, respectively the last presidents of the Orange Free State. Another key adviser was Abraham Fischer (1850-1913), a Capetown-trained lawyer and skilled Boer statesman. Let’s stay with this suave, skilled, successful leader for a moment.

By the time the Orange Free State became the Orange River Colony, Abraham Fischer had become a key player in government. Both presidents Steyn of the Orange Free State and Kruger of neighboring Transvaal had relied on his counsel and judgment, and he was widely considered one of the Boers’ most adept strategists. When Lord Selbourne moved in 1905 to establish self-government in the Orange River Colony, the governor, by then Sir Hamilton Goold-Adams, asked Fischer to form a ministry. The self-governed Orange River Colony operated for only three years, from 1907 to 1910, and the colony itself existed for less than 10 years total; but they were years of peace, prosperity and effective governance. Despite having to cope with swings in business cycles, agricultural drought and political dissension, the regime and its diligent civil service managed to produce a surplus each year without raising taxes. (The diamond mines helped.) The railways expanded and schools (for whites) were improved. After the union, Fischer was appointed interior minister of the new South African government, though he only served three years before his death in 1913 at age 63.

As a Boer, Fischer could have been expected to harbor similar racist views as compatriots like Brand, Kruger and Smuts. Fischer and Smuts were suave diplomats who played a key role in reconciling Boers and Brits — no mean feat after a century of antagonism and occasional bloodletting that culminated in Cecil Rhodes’ failed Jameson Raid of 1896 and the confrontation between Kruger and Lord Kitchener in the Second Boer War of 1899-1902. By 1910, thanks to the efforts of Fischer, Smuts and others, the two “white tribes” of southern Africa had figured how to lay down their arms, make peace and enjoy the spoils in a new, bilingual state.

Fischer and Smuts helped bring Boers and Brits together, but they were less enthusiastic about reconciling whites and blacks. During Fischer’s short Orange River Colony mandate, he did manage to organize a Department of Native Affairs. Whether or not this was a promising development I don’t know. But blacks would never vote in the Orange River Colony, any more than they did in the Orange Free State.

The reason I pursue this matter of Abraham Fischer and black south Africans is because of his progeny. His son Percy became a judge, and I know little about him. However his grandson, Abraham Lewis (“Bram”) Fischer, was a horse of an entirely different hue. Get ready for this story.

Bram Fischer was born in 1908, studied at Oxford and became a lawyer. During a trip to Europe in 1932 he visited Russia. The 24-year-old wrote to his father that he saw similarities between the abuses of Russian peasants and South Africa’s blacks. Now, here was a sentiment you would not expect to hear, coming from a scion of Boer aristocracy. Yet Bram Fischer would not be eterred. Somewhere along the line, he had picked up the idea that South Africa’s racism not only was wrong, but would destroy the nation unless it changed. (Remarkably similar views were expressed decades earlier by F.X. Merriman, aide to the Cape Colony Gov. Molteno, who warned: “The greatest danger to the future lies in the … vain hope of building up a state in a narrow, unenlightened minority.”) These convictions led Bram Fischer to join the South African Communist Party, where he became a leader and key strategist. He collaborated with a young man named Nelson Mandela of the African National Congress, a fellow graduate of the racially inclusive Witwatersrand University in Johannesburg. Fischer forswore the racist Boer ideology, was shunned by friends and colleagues, and continued to wage the good fight over the years. His proudest moments may have come in 1961, when he successfully defended Mandela and others against charges of treason; and In 1964, when the ANC leader was tried again, convicted and sentenced to life in prison — another victory for Fischer’s defense team, since the prosecution had called for the death penalty.

In saving the life of South Africa’s future president, Fischer sacrificed his own freedom. Soon after the trial, Fischer was arrested and put on trial for his activities with the South African Communist Party, long outlawed by the government. There was never any doubt about his “guilt” — the party was illegal, and Bram Fischer was one of its pillars. Somehow, Fischer had kept his ”subversive” activities out of view — up to now. As friends urged him to take Mandela’s case, Fischer knew the public spectacle of a treason trial would expose him. Nevertheless, he persisted. One friend who had urged him to take the case, not knowing of Fischer’s risk, said later: “He deserves the Victoria Cross.”

I know I should move on, but this story is just too good to leave at this point, so please bear with me. Before his trial, Fischer was allowed to travel to London to handle a patent case. The judge let him leave South Africa because upon his promise to return. “I am an Afrikaner,” Fischer said. “My home is South Africa. I will not leave my country because my political beliefs conflict with those of the Government.” Return he did — but not to sit in a courtroom. Instead, Fischer went underground to continue his fight against apartheid. He wrote to the judge:

“… (My) absence, though deliberate, is not intended in any way to be disrespectiful. Nor is it prompted by any fear of the punishment which might be inflicted on me. Indeed I realize fully that my eventual punishment may be increased by my present conduct …

“My decision was made only because I believe that it is the duty of every true opponent of this Government to remain in this country and to oppose its monstrous policy of apartheid with every means in his power. That is what I shall do for as long as I can. …”

Fischer was found guilty in 1965 in absentia and disbarred. Later that year he was arrested and put on trial again for trying to overthrow the government. He was convicted and received a life sentence. Before long the personable and dynamic inmate became a prison leader, popular even with the warden. While prisoners in South Africa at the time usually were released early, political prisoners were singled out for harsh treatment, compelled to serve every day. Fischer’s life sentence was shortened only by fate — he died of cancer in 1975. The authorities punished him to the end, neglecting his treatment. Only in his last weeks did the regime — pressed by the public and international outcry — allow him to die at his brother’s home in Bloemfontein. Unlike Mandela, Fischer would not see apartheid fall in 1991.

Since his death, Fischer’s reputation has been restored. In 2002, he became the first South African reinstated to the bar posthumously. The airport in Bloemfontein was renamed Bram Fischer International Airport in 2012. Oxford hosts an annual Bram Fischer Memorial Lecture.

Mandela counted Fischer among the “bravest and staunchest friends of the freedom struggle that I have ever known.” He noted that with his pedigree and talents, Fischer could have become South Africa’s prime minister. “As an Afrikaner whose conscience forced him to reject his own heritage and be ostracized by his own people, he showed a level of courage and sacrifice that was in a class by itself,” Mandela said. “No matter what I suffered in my pursuit of freedom, I always took strength from the fact that I was fighting with and for my own people. Bram was a free man who fought against his own people to ensure the freedom of others.”

I am left wondering — without answers as yet — whether the spark that led to Bram Fischer’s awakening was kindled somehow by the judicial integrity of his father, and before that by his grandfather Abraham Fischer, the one and only president of the Orange River Colony. (I wish someone would find out …)

I will end this tale with more from Bram Fischer, because I think his words resonate today as well as when they were written more than half-a-century ago. In his letter to the court, Fischer declared that he and his co-defendants were being punished “for holding the ideas today that will be universally accepted tomorrow.” More of his words:

“What is needed is for White South Africans to shake themselves out of their complacency, a complacency intensified by the present economic boom built upon racial discrimination. Unless this whole intolerable system is changed radically and rapidly, disaster must follow. Appalling bloodshed and civil war will become inevitable because, as long as there is oppression of a majority, such oppression will be fought with increasing hatred.

“… when the laws themselves become immoral and require the citizen to take part in an organized system of oppression — if only by his silence and apathy — then I believe that a higher duty arises. This compels one to refuse to recognize such laws.”

And: “All the conduct with which I have been charged has been directed towards maintaining contact and understanding between the races of this country. If one day it may help to establish a bridge across which white leaders and the real leaders of the non-white can meet to settle the destinies of all of us by negotiation, and not by force of arms, I shall be able to bear with fortitude any sentence which this court may impose on me. It will be a fortitude, my Lord, strengthened by this knowledge, at least, that for the past 25 years I have taken no part, not even by passive acceptance, in that hideous system of discrimination which we have erected in this country, and which has become a byword in the civilized world.”

Dear reader, we have wandered far indeed from the world of stamp collecting. Isn’t it marvelous? I searched in vain for a stamp commemorating Bram Fischer or his grandfather Abraham. Too bad. Bram Fischer surely ranks as one of history’s great champions of equality and freedom.

TO BE CONTINUED

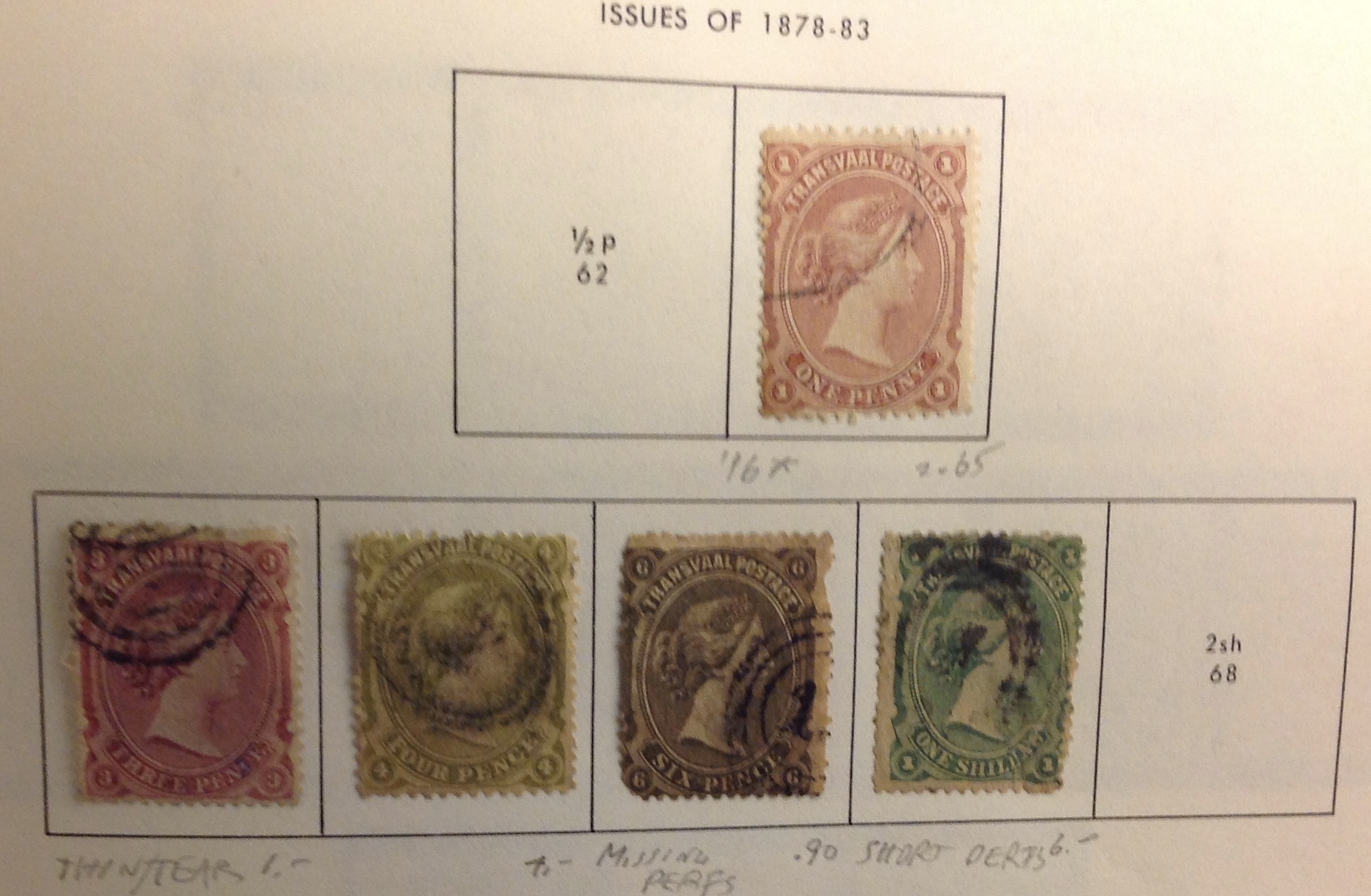

ZAR/Transvaal: Philatelic Addenda — Into the Weeds!

Here is the coat of arms of ZAR (Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek) that was painted on the side of ZAR President Paul Kruger’s wagon. Since the coat of arms is the only design on ZAR stamps, it’s useful to have a clear depiction for easy reference. Note inside the shied the lion at left, an armed Boer to the right, and a voortrekker’s wagon underneath. In the middle is the anchor symbol of the Cape of Good Hope, part of a shared British/Boer heritage. The motto, “Eendragt Maakt Magt,” translates as “Oneness Makes Might.”

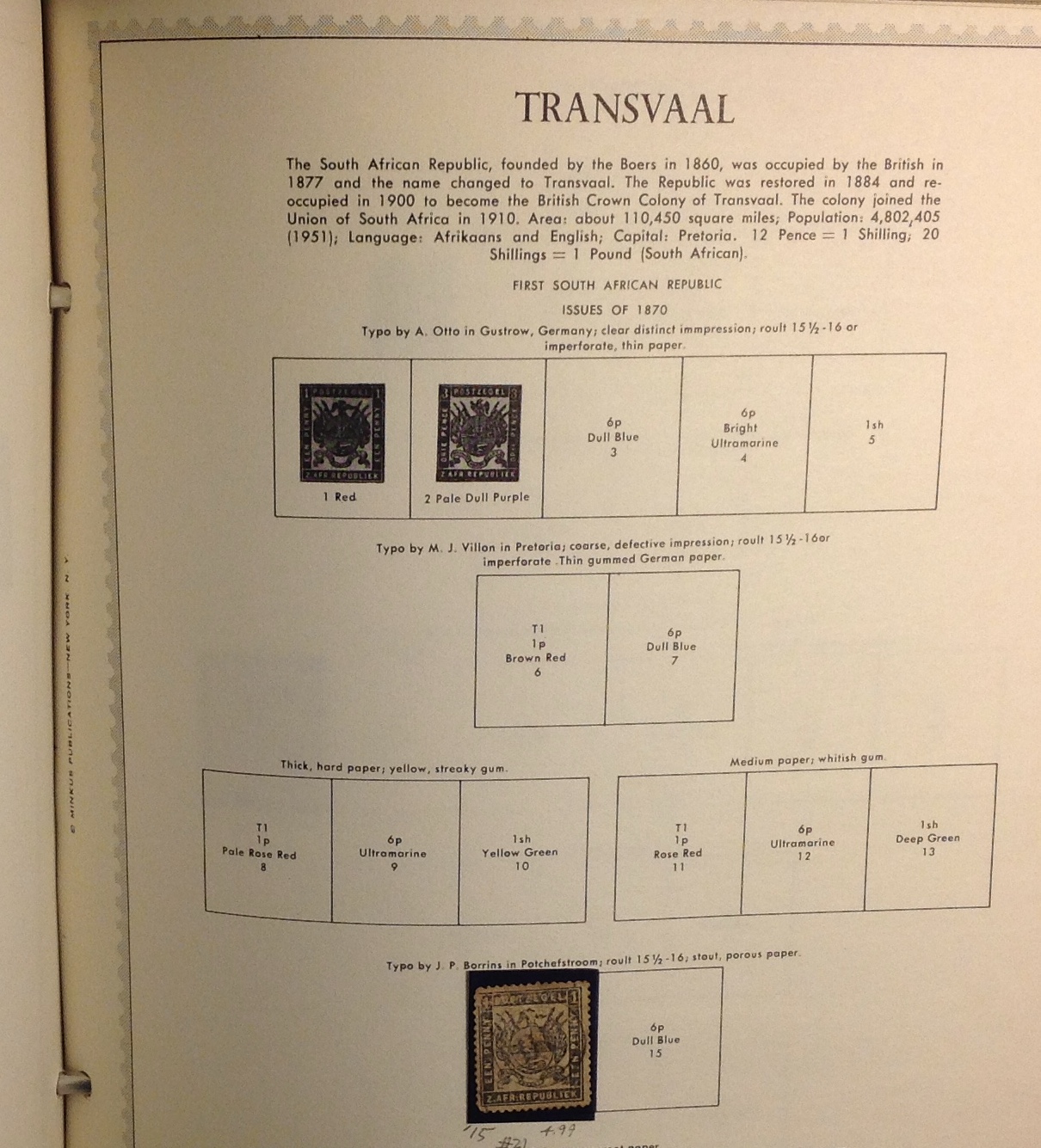

Into the tall grass of philatelic esoterica! This is where stamp-collecting gets interesting — to stamp collectors. This short essay is for general readers, though. By embarking on this brief expedition into the high veld of ZAR/Transvaal philately, you can glimpse varieties of design and printing, amid other oddities that delight the collector, invite speculation and excite the imagination! Imagine, being excited by printing varieties. That’s part of stamp-collecting. Well, this won’t take long, and I believe you, General Reader, will have a bit of fun coming along on this quick tour, presented as several addenda.

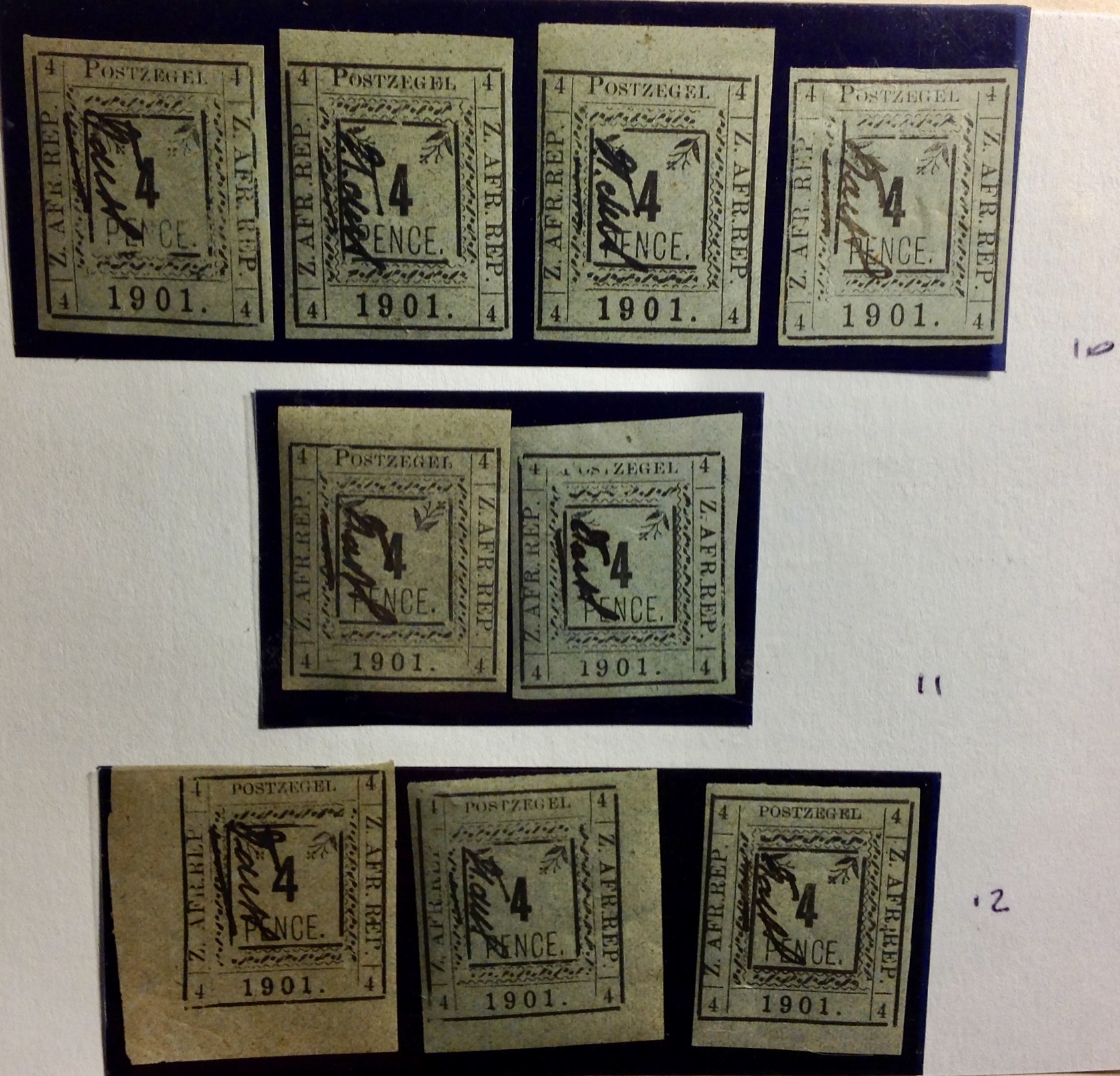

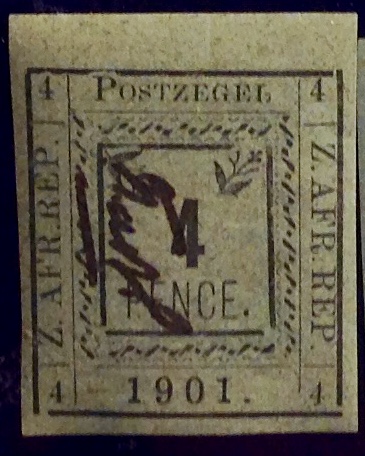

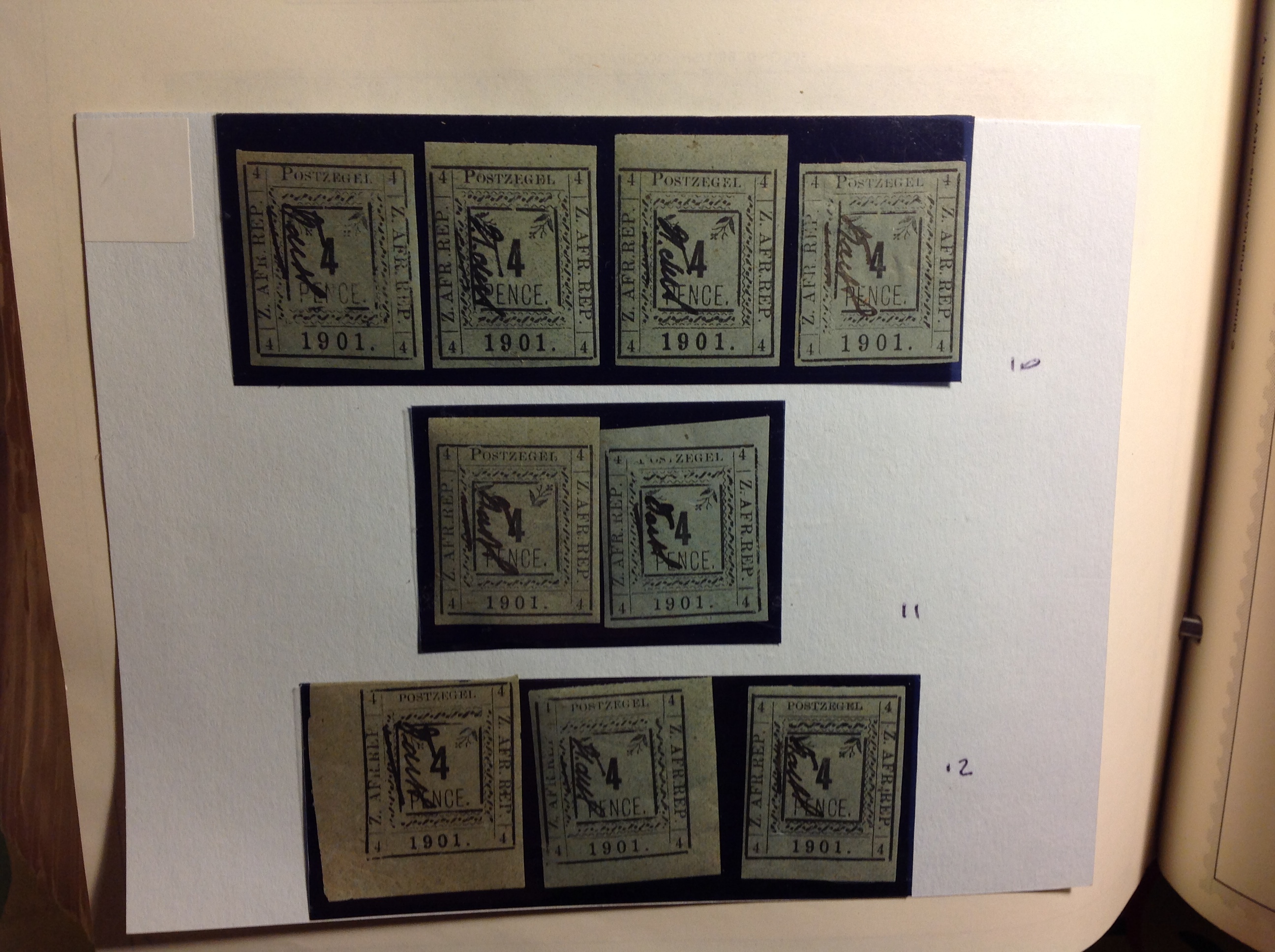

The Pietersburg issues of March-April 1901 are fairly expensive, but very exotic. Consider: they were on sale for only a few weeks, during the desperate last days of the Boers’ ZAR (Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek). ZAR President Paul Kruger had  already left the country. The provisional government in Pietersburg was running low on stamps — a truly dire circumstance! — so the authorities came up with this crude, type-set design. There are three design varieties. I have multiple examples of each type, all with the same value of 4 pence. Each stamp is hand-signed/cancelled, and catalogs at between $25 and $40. I recall I paid about $40 for the lot. Quite a deal, eh? Below are enlargements clearly illustrating the differences. (Remember, we are in the tall grass, so stay close.)

already left the country. The provisional government in Pietersburg was running low on stamps — a truly dire circumstance! — so the authorities came up with this crude, type-set design. There are three design varieties. I have multiple examples of each type, all with the same value of 4 pence. Each stamp is hand-signed/cancelled, and catalogs at between $25 and $40. I recall I paid about $40 for the lot. Quite a deal, eh? Below are enlargements clearly illustrating the differences. (Remember, we are in the tall grass, so stay close.)

VARIETY ONE (left): The date is large. The “P” in Postzegel is large.

TWO (left): The date is smaller. The “P” is still large.

THREE (right): The date is small. So is the “P.”

Can you spot the differences? Isn’t this fun? (For more about the Pietersburg issues, see FMF Stamp Project blog post of 3/17/17.)

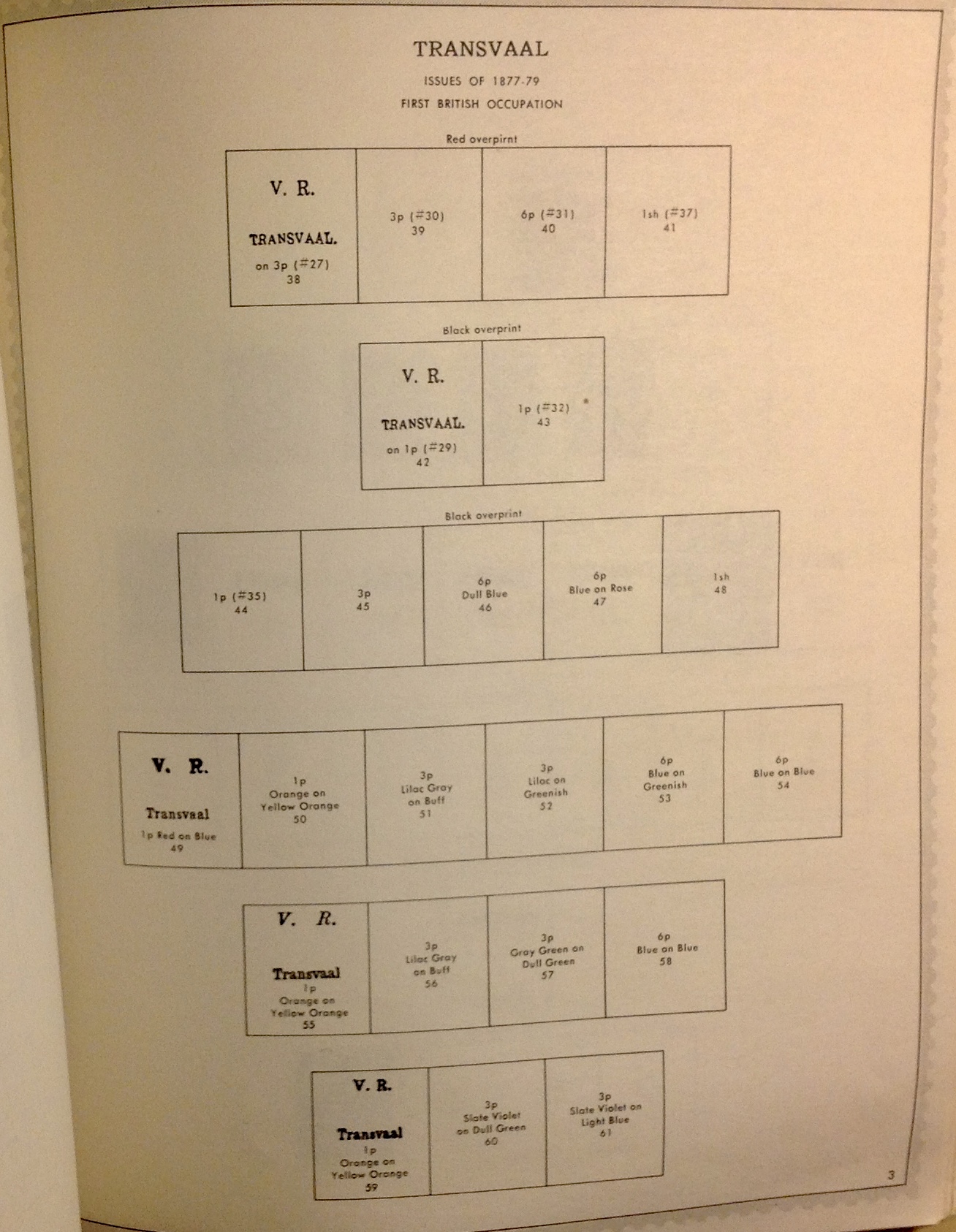

It pains me to have to display this page from my album without any stamps in it. It’s just that the “VR” overprints on ZAR stamps are quite rare and expensive, and because they are so dull, I am not motivated to invest in one. I probably will, though, sooner or later, just to have it on the page to make things more interesting.

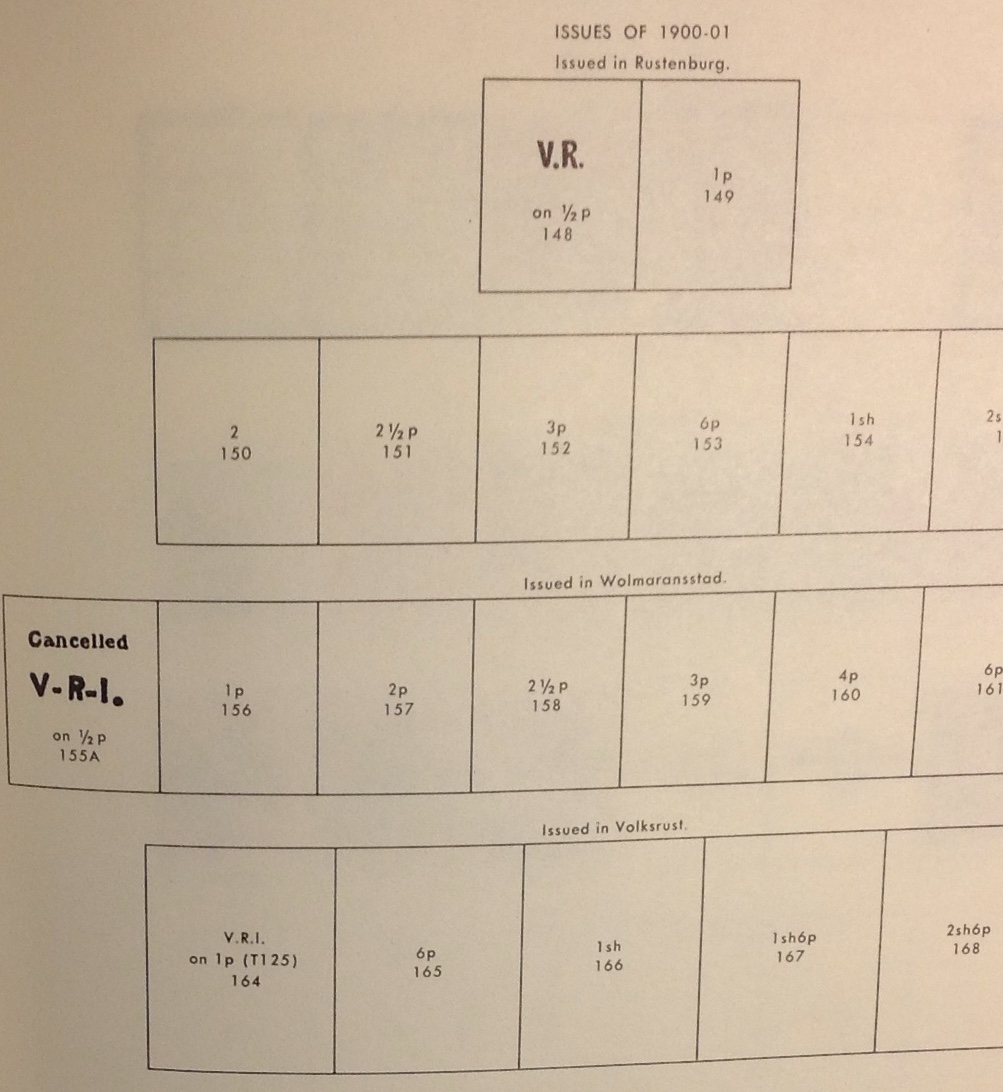

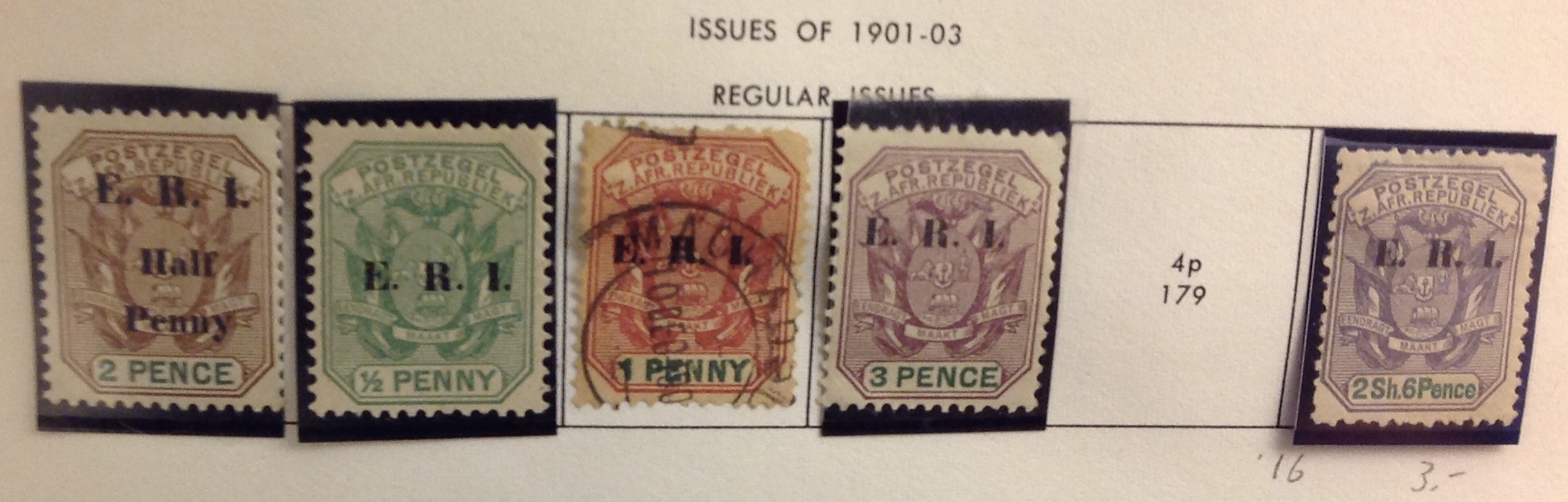

B. Why were so many overprinted stamps released in 1900? The Scott catalogue lists 49 varieties with “V.R” or “VRI” overprints — or “E.R.I.” after Victoria died and Edward VII took over in 1901. Come to think of it, there were an awful of of “VR” overprints back in 1878-9, during the first British occupation — 46 varieties listed in Scott. It was efficient to use up existing stocks of stamps, I suppose. But it looks kind of sloppy.

The early overprints of 1900 were issued under military authority in Lydenburg, Rustenburg, Schweizer Reneke and Wolmeransstad. Stamps from Schweizer Reneke carry a handstamp, “Besieged” (left, below). These are very rare stamps indeed. Remember Baden-Powell and “Mafeking Besieged”? (See blog post, December 2019, for the whole story in brief, with stamps.) In his history, “The Great Boer War,” Bryon

This is a very rare, very expensive stamp, pictured here on the Internet. It’s originally a green 1/2d. stamp from Cape of Good Hope (see Hope in her dress?). Along the left side is a hand-stamp, “BESIEGED,” and the cancellation reads “Schweizer Reneke Z.A.R. 12 Sept. 00.” One wonders how mail got through the siege … was there a gentlemen’s agreement? An ad hoc postal convention?

Farwell writes: “The sieges of Kimberley, Ladysmith and Mafeking, avidly followed while they were in progress, widely celebrated when they were raised, have been given their place in history. Rarely mentioned, however, is the siege of Schweizer Reneke, a small town in the western Transvaal which was invested on 19 August 1900 and not relieved until 9 January 1901. No one remembers the name of George Chamier, the garrison’s commander. The gallant defenders of Schweizer Reneke had the misfortune to be besieged at a time when the people at home were bored with sieges; they had had enough; besides, there were no newspaper correspondents there. And the British public, which exhausted itself cheering for plucky B-P and the relief of Mafeking, raised not a single cheer for the relief of Schweizer Reneke.”

This proliferation of “VIctoria” overprints invites speculation, if not further research. Was it because the military authorities didn’t have a supply of the old Victorian Transvaal stamps on hand in the field? Perhaps by 1900, that profile from 1878 would no longer be age-appropriate for the tottering Dowager Queen. Why not just keep using local stamps? Was it necessary to declare philatelic victory so fast? It certainly seems the Brits wanted to establish their supremacy toot sweet. So they cobbled together crude overprints and gave existing ZAR stock the royal brand. Take that, you uncouth Boers!

The catalogue prices for these sets rise into the hundreds — they must have been quite limited issues. But what truly deters a casual collector like me, in addition to the daunting prices, the rather boring differences between the overprints, not to mention the dull stamps underneath, is the following:

C. The catalogue warns: “Nos. 202 to 213 have been extensively counterfeited.” … ”Beware of counterfeit.” … “Excellent counterfeits of Nos. 246 to 251 are plentiful …”

What is it with all this counterfeiting? Was there a fad for collecting these dull and wacky Transvaal stamps, all of them with the same design? Was the see-saw history of Transvaal a spectator sport in jolly old England, such that collectors competed to

Are these stamps real, or counterfeit? Is the overprint legit or not? If one is real and the other counterfeit, is it still a counterfeit? Hasn’t the overprint legitimized the stamp? Does anyone care?

show off their sets of Victorian overprints on ZAR stamps from battleground towns in the veld? This is sheer speculation, folks, but by the end of the 19th century, stamp collecting had become quite a fad, so I wouldn’t be a bit surprised if there was some titillation in GB as Transvaal and ZAR swung back and forth in their bloody joust for white supremacy.

Some sets are questionable as “reprints,” then are listed with overprints as “counterfeit.” Which makes one wonder — are we looking at a counterfeit overprint on a counterfeit stamp? Is the overprint counterfeit and the stamp genuine, or vice versa? Seems like a long shot that you’d actually get a real stamp with a real overprint.

For reference in this section, here again is a clear rendition of the Boer coat of arms, as painted on Paul Kruger’s wagon.

D. Actually, the counterfeiting started much earlier — in fact, right at the beginning of ZAR postal history in 1869. Scott catalogue editors note that “So-called reprints and trial impressions of the stamps in types A1 and A2 are counterfeit. This applies to Nos. 1 to 96.” Sometimes the only way to tell genuine from forgery is by the color shade. How discouraging!

Nevertheless, I persisted and succeeded in getting this couple of early beauties — Nos. 21

and 31, illustrated here. The Scott catalogue helped a lot in distinguishing tell-tale signs of forgery, leaving me fairly confident that the stamps I bought are the genuine article. Allow me to accompany you a bit further into the philatelic weeds while we pick our way gingerly past the telltale signs of forgery in search of the real and the true — as best we can.

and 31, illustrated here. The Scott catalogue helped a lot in distinguishing tell-tale signs of forgery, leaving me fairly confident that the stamps I bought are the genuine article. Allow me to accompany you a bit further into the philatelic weeds while we pick our way gingerly past the telltale signs of forgery in search of the real and the true — as best we can.

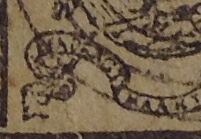

One clue is in the motto, “Eendragt Maakt Magt” — Oneness Makes Might. In the genuine stamp, the “D” in the word “EENDRAGT” is outsized, touching the ribbon. In forgeries, the “D” is the same size as the other letters inside the ribbon.

Look for the “D” in “EENDRAGT” — notice how it is outsize and touches the top line of the ribbon. This is a sign of authenticity.

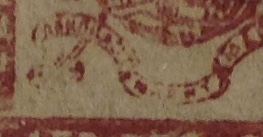

A second clue: In the genuine stamp, the eagle’s eye is a dot in a white face. In forgeries, the eye is a blob and the beak is hooked.

In both No. 21 (above) and No. 31 (below), the eagle looks like it has a nice “dot” for an eye, as in the genuine stamp, and not the “blob” of the forgeries. Furthermore, the beak in both stamps is straight, not hooked — another good sign. I must say, though, the fearsome eagle looks a lot like Woodstock from “Peanuts.”

Please examine these extreme close-ups. What do you think? Are they real, or counterfeit? (I should point out that the stakes are not that high: No. 21 has a catalogue value of $17.50, while No. 31 catalogues at $40.) My claim is that I did due diligence in researching and buying these stamps online, and I think the evidence is fairly solid that these are the genuine article.

E. While we are here in the weeds, let’s examine another philatelic oddity — sets from the ZAR’s restoration after 1884. Paul Kruger’s administration put out set after boring set featuring the ZAR’s coat of arms. (Many of these stamps also were counterfeited, for reasons I find inexplicable but am not sufficiently interested or  prepared to pursue.)

prepared to pursue.)

This particular oddity involves sets featuring a “wagon with two shafts,” and a later set depicting a “wagon with pole.” The extreme close-up illustrations below should give you a clear idea what we’re talking about.

This particular oddity involves sets featuring a “wagon with two shafts,” and a later set depicting a “wagon with pole.” The extreme close-up illustrations below should give you a clear idea what we’re talking about.

See the two shafts on the wagon?

Now do you see the single pole?

For reference, here is a close-up of the wagon in the coat-of-arms painted on Paul Kruger’s wagon. It’s clearly a pole, not two shafts.

Before anyone gets excited over the distinction, let me point out that both sets can be had for under $30. This is not a matter of rarities, just oddities. Why change from two shafts to a single pole? Is the pole more historically accurate? Is the pole truer to the formal depiction in the ZAR coat of arms? Most fervently, it is hoped that the pole is well-suited to help the Boer oxen haul the trekker’s wagon out of the philatelic weeds so we can get back to the narrative!

THIS IS THE END OF ZAR/TRANSVAAL ESSAYS, BUT THE FMF STAMP PROJECT IS TO BE CONTINUED …

ZAR/Transvaal: The Story Continues

Anecdotes and legends swirl around Paul Kruger, celebrated in his day as “Oom Paul” — Uncle Paul. He was the immovable cornerstone of Boer aspirations late-19th-century southern Africa, the Keeper of the Vow, even as he was reviled as a racist, obstructionist rube. Kruger was born on the eastern edge of the Cape Colony in 1825. His family had lived in south Africa since 1668. The Krugers moved across the Orange River in 1836 as part of the Great Trek. He had little or no formal education outside of the Bible. He grew up fast amid skirmishing Boers, Brits and Bantus. By his teenage years, Kruger was already an accomplished frontiersman, horseman and guerrilla

Anecdotes and legends swirl around Paul Kruger, celebrated in his day as “Oom Paul” — Uncle Paul. He was the immovable cornerstone of Boer aspirations late-19th-century southern Africa, the Keeper of the Vow, even as he was reviled as a racist, obstructionist rube. Kruger was born on the eastern edge of the Cape Colony in 1825. His family had lived in south Africa since 1668. The Krugers moved across the Orange River in 1836 as part of the Great Trek. He had little or no formal education outside of the Bible. He grew up fast amid skirmishing Boers, Brits and Bantus. By his teenage years, Kruger was already an accomplished frontiersman, horseman and guerrilla  fighter. In his memoirs he said he shot his first lion at 16, though others say he was 14, or perhaps 11. After breaking a leg in an accident, the story goes, Kruger repaired his wagon and drove it to safety — though one leg was shorter than the other thereafter. He spoke Dutch, basic English and several African languages — and believed all his life that the Earth was flat.

fighter. In his memoirs he said he shot his first lion at 16, though others say he was 14, or perhaps 11. After breaking a leg in an accident, the story goes, Kruger repaired his wagon and drove it to safety — though one leg was shorter than the other thereafter. He spoke Dutch, basic English and several African languages — and believed all his life that the Earth was flat.

Kruger would marry twice and father 17 children. As an adult, he cut an odd figure with his bulk, his rustic attire, a wide, uneven fringe of facial hair and an unsmiling, sphinx-like demeanor. His habits were not of the manor born. Some imperialists underestimated the future four-term president of the ZAR, considering him unsightly, even ugly with his short frock coat, chin whiskers and top hat. Some saw only greasy hair, a worn pipe protruding from his pocket, and copious spitting — in short, here was little more than a vulgar, backveld peasant.

But Kruger’s capacity for leadership, his zeal for autonomy and his unshakable faith set him apart. He caught the eye of Andries Pretorius, the Boer leader who founded the short-lived Republic of Natalia. Biographer Johannes Meintjes observed that Pretorius saw in Kruger a man behind whose “tough exterior was a most insular person with an intellect all the more remarkable for being almost entirely self-developed.” Later on, a discerning Lady Phillips was said to have commented on the president’s comings and goings in Pretoria in his

But Kruger’s capacity for leadership, his zeal for autonomy and his unshakable faith set him apart. He caught the eye of Andries Pretorius, the Boer leader who founded the short-lived Republic of Natalia. Biographer Johannes Meintjes observed that Pretorius saw in Kruger a man behind whose “tough exterior was a most insular person with an intellect all the more remarkable for being almost entirely self-developed.” Later on, a discerning Lady Phillips was said to have commented on the president’s comings and goings in Pretoria in his  stained frock coat and tall hat: “I think his character is clearly to be read in his face — strength of character and cunning.”

stained frock coat and tall hat: “I think his character is clearly to be read in his face — strength of character and cunning.”

Not yet 30 in 1852, Kruger was present for the signing of the Sand River Accords that ended the First Boer War and established the Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek. He led commandos for the ZAR against Basoto and Tswana tribes, and was commandant-general from 1863-73. After Britain’s annexation of  ZAR/Transvaal in 1878, it didn’t take long for Kruger to begin agitating for new arrangements with the Crown. In 1880 Kruger, Martinhus Pretorius and Joet Joubert were called to confer with the British overlords, and on December 16 the Boer leaders declared renewed independence for the ZAR. Shooting and bloodshed followed, with the Boers prevailing at Laing’s Nek, Ingogo and beyond. Rather than pressing imperial interests, British Prime Minister William Gladstone chose to negotiate, granting the Boers local autonomy and in the London Convention of 1884, full independence under a new president — Paul Kruger.

ZAR/Transvaal in 1878, it didn’t take long for Kruger to begin agitating for new arrangements with the Crown. In 1880 Kruger, Martinhus Pretorius and Joet Joubert were called to confer with the British overlords, and on December 16 the Boer leaders declared renewed independence for the ZAR. Shooting and bloodshed followed, with the Boers prevailing at Laing’s Nek, Ingogo and beyond. Rather than pressing imperial interests, British Prime Minister William Gladstone chose to negotiate, granting the Boers local autonomy and in the London Convention of 1884, full independence under a new president — Paul Kruger.

The British continued to call the region Transvaal, though the stamps issued after 1884 all carried the name “Z.Afr.Republiek,” in line with a postal convention between ZAR, the Orange Free State and Cape Colony. In what looks like a cheeky maneuver, the Boers also took the 4d. stamp from the Queen Victoria series of 1878 and surcharged it “Een Penny” — simultaneously asserting their Afrikaner supremacy and devaluing a British artifact from four pence to one penny. Cute! Other than that, all the new ZAR stamps, as before, had the same design: the Boer coat of arms.

The British continued to call the region Transvaal, though the stamps issued after 1884 all carried the name “Z.Afr.Republiek,” in line with a postal convention between ZAR, the Orange Free State and Cape Colony. In what looks like a cheeky maneuver, the Boers also took the 4d. stamp from the Queen Victoria series of 1878 and surcharged it “Een Penny” — simultaneously asserting their Afrikaner supremacy and devaluing a British artifact from four pence to one penny. Cute! Other than that, all the new ZAR stamps, as before, had the same design: the Boer coat of arms.

The ensuing years were a period of prosperity and growth for the ZAR, particularly after the discovery of rich gold reefs in Witwatersrand. Friction grew between Boers and the burgeoning population of “uitlanders” — non-Boer settlers. The ZAR and the Orange Free State strengthened their ties, and smaller Boer republics like Stellaland were brought under the ZAR’s wing. Conflicts between Boers and Brits only increased after Cecil Rhodes, the swashbuckling imperialist, became Prime Minister of the Cape Colony in 1890. His British South Africa Company impinged on ZAR/Transvaal from Matabeleland and Mashonaland, and non-Boer settlers in the  ZAR increased their pressure for full citizenship rights and privileges. Paul Kruger with his plain politics, his biblical certainty and stubborn commitment to Boer supremacy, was ill-suited to the task of guiding his sturdy wagon of state through the economic expansions and upheavals of the century’s end.

ZAR increased their pressure for full citizenship rights and privileges. Paul Kruger with his plain politics, his biblical certainty and stubborn commitment to Boer supremacy, was ill-suited to the task of guiding his sturdy wagon of state through the economic expansions and upheavals of the century’s end.

Notwithstanding the pressures, Kruger was at the height of his popularity among the Boers in 1898, winning election to his fourth term by record margins. By now, Transvaal had its long-dreamed-of railroad to the Indian Ocean coast at Delagoa Bay, in Portuguese Laurenco Marques — celebrated in a stamp released in 1895 to inaugurate “penny postage” in the ZAR. The gold boom had created the mining town of Johannesburg, which already had grown  bigger than Cape Town. The uitlanders and their British surrogates, including Cecil Rhodes, had been humiliated by the failed Jameson Raid of 1896, and Kruger had a strong ally and protege in his bright young state attorney, Jan Smuts.

bigger than Cape Town. The uitlanders and their British surrogates, including Cecil Rhodes, had been humiliated by the failed Jameson Raid of 1896, and Kruger had a strong ally and protege in his bright young state attorney, Jan Smuts.

In 1898, Kruger and Smuts became enmeshed in negotiations with the British in Bloemfontein that broke down over seemingly intractable differences between Boers and the disenfranchised

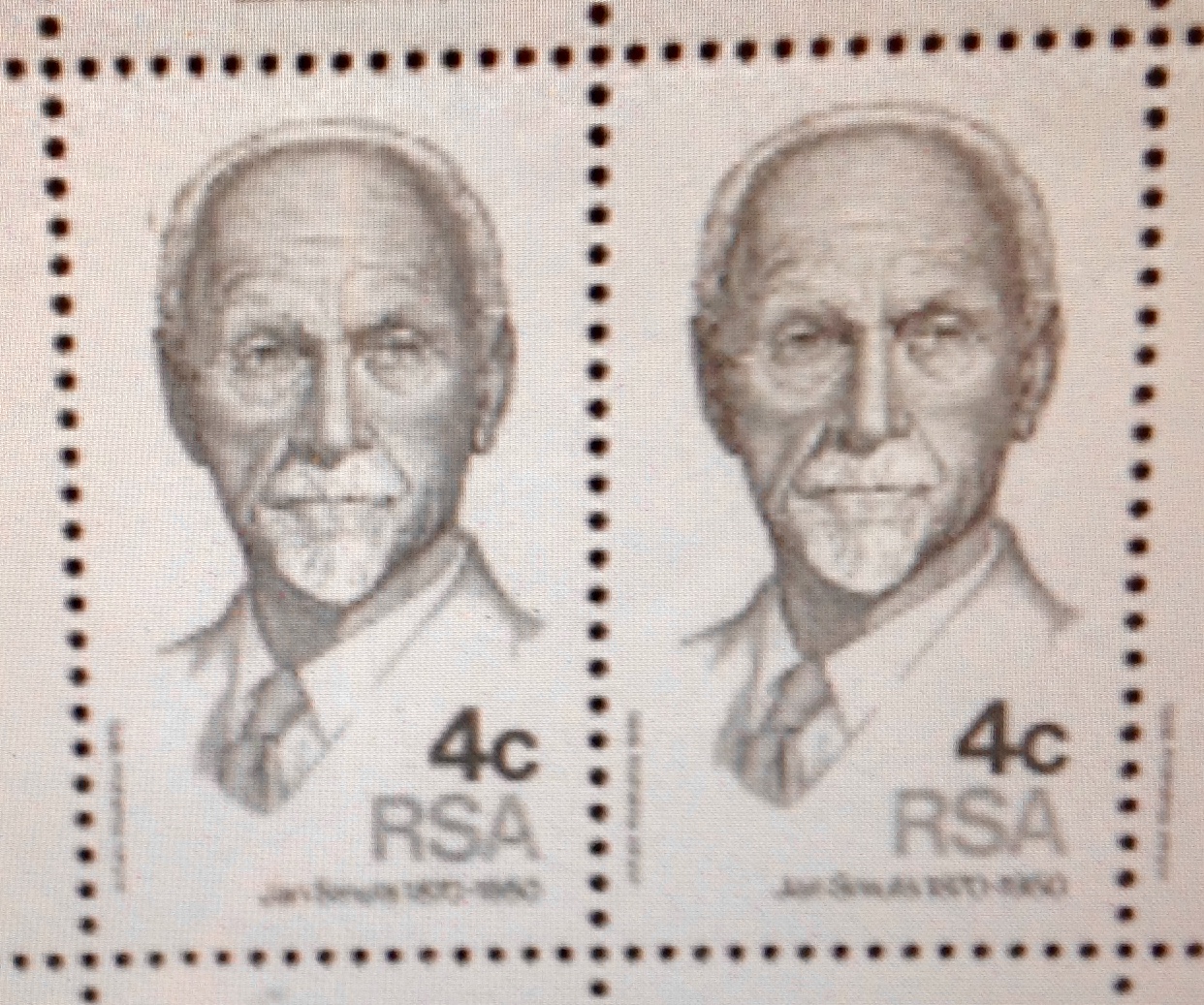

Jan Smuts

uitlanders. Though Smuts thereby helped to precipitate the Second Boer War (1899-1902), which brought a permanent end to the ZAR, Smuts also saw to it that the Boer people emerged from the fighting in a strong position. Over the years he would serve twice as prime minister of the Union of South Africa. He became an intimate of Winston Churchill and a statesman of international stature. Suave and polished, unlike his mentor Paul Kruger, the durable Smuts was the only delegate to sign the peace treaties ending both World Wars I and II. He was a member of Britain’s war cabinet and helped establish the RAF. His vision shaped the League of Nations. He wrote the first draft of the preamble to the United Nations Charter. And yet, his racist policies laid the foundations of apartheid. But I digress.

In this turn-of-the-century cartoon, a dour Queen Victoria plays a game of chess with wily opponent Paul Kruger, while Lord Kitchener looks on grimly. “In the lower spheres of diplomacy Mr. Kruger was a master,” E B Iwan-Müller asserted. “He was quick in detecting the false moves made by his opponents, and an adept in turning them to his own advantage; but of the large combinations he was hopelessly incapable. To secure a brilliant and conspicuous success today he was ready to squander the prospects of the future, if, indeed, he had the power of forecasting them. He was what I believe soldiers would call a brilliant tactician, but a hopeless strategist.”

By the time the Second Boer War was declared Oct. 11, 1899, Paul Kruger had became a popular figure internationally among critics of British imperialism in Africa. By now 74 years old, Kruger no longer led commandos — though he sent four of his sons, six sons-in-law and 33 grandsons. True to form, the Boers started out fighting for their homesteads with pluck and luck. They won early victories in Natal

Enter Kruger, accompanied by his secretary Madie Bredell, leaves Africa. Soon after Kruger’s death, Smuts told the British humanitarian campaigner Emily Hobhouse: “He typified the Boer character both in its brighter and darker aspects, and was no doubt the greatest man—both morally and intellectually—whom the Boer race has so far produced. In his iron will and tenacity, his ‘never say die’ attitude towards fate, his mystic faith in another world, he represented what was best in all of us.”

and the Cape Colony, and laid siege to the strategic cities of Kimberley, Ladysmith and Mafeking. But the superior forces and resources of the British soon prevailed — Kimberley and Ladysmith were relieved in February, 1900, and Mafeking two months later. The British were in Johannesburg by May 30. Many demoralized Boers simply went home. An unyielding Kruger abandoned his capital, Pretoria, and settled with his family in the “Krugerhof” at Waterval Onder. Britain’s Lord Kitchener formally annexed the Orange Free State May 24 and claimed the ZAR Sept. 1. New stamps appeared in the ZAR with the overprint “V.R.” to re-confirm Queen Victoria’s dominion. Kruger was unbending and declared Kitchener’s decrees “not recognized.” On Sept. 11, he left the ZAR/Transvaal, crossing into Mozambique on his coveted railroad. Ultimately he went into exile. He died surrounded by his family in Clarens, Switzerland in 1904.

Erratic fighting continued through 1901. On the philatelic front, Queen Victoria died Jan. 22, 1901, and the “VR” overprint (above) was replaced by “ER” (below) for her son and heir, Edward VII.

I recently acquired this collection of “Pietersburg” stamps. All of them are the same denomination — 4 pence — yet there are three varieties. I’ll talk more about this in Part III.

The ZAR government, now re-located to Pietersburg, was running short of stamps by March 1901. The besieged Boers issued a new series, crudely type-set and hand-signed. The stamps were only in use for a matter of weeks — the British captured Pietersburg April 9. Because of this short time span, the desperate cause represented, and the varieties of production that resulted in subtle design changes, the “Pietersburg” stamps are catnip to specialist collector-cats. More on this later.

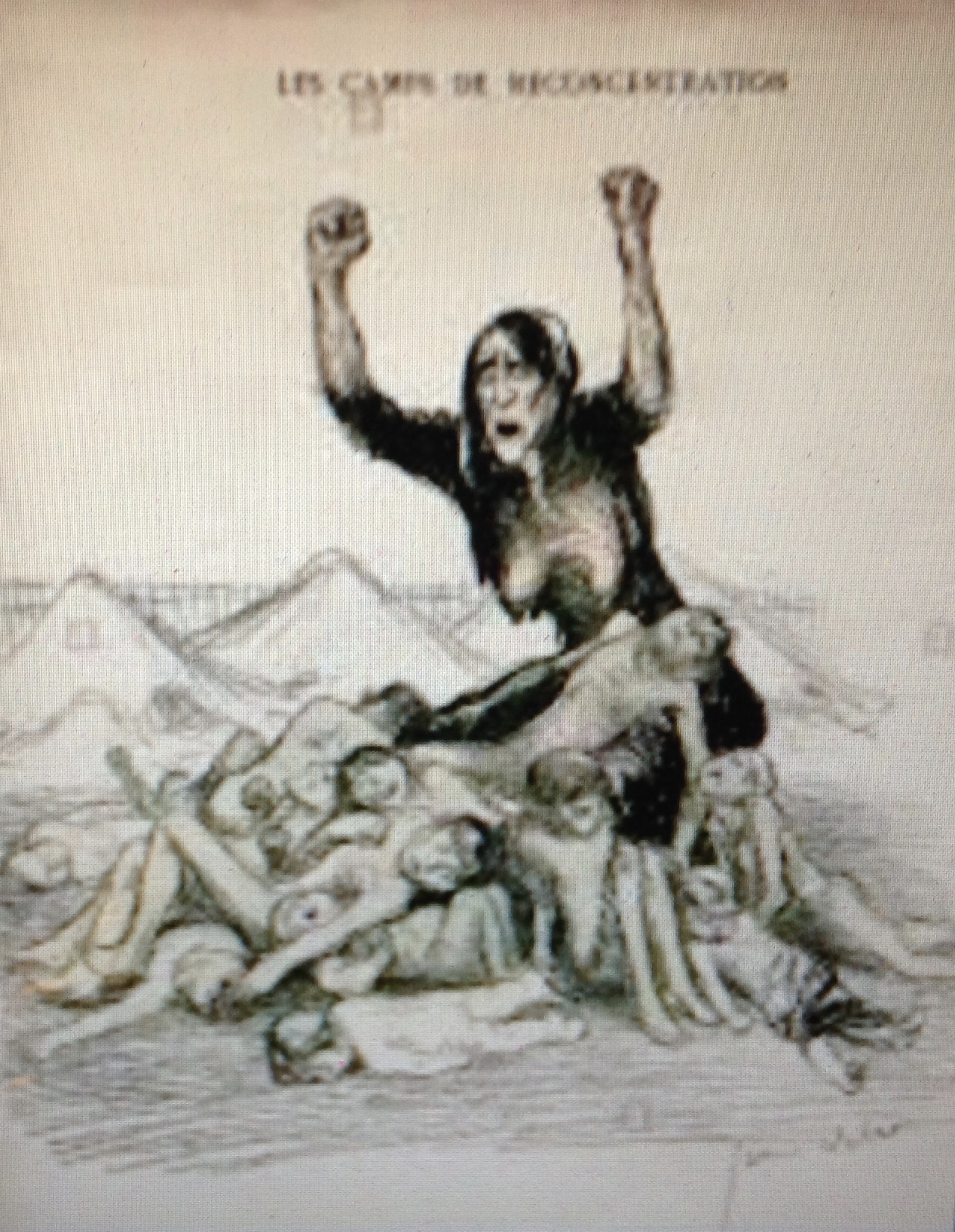

French graphic from the era depicts the horrors of “les camps de deconcentration”

While the Boers were holding out, Kitchener adopted a punishing “scorched earth” policy, burning and razing Boer farms and homesteads. Thus died the Boer dream of the good life, the lekker lewe of limitless land and divine blessing. The British set up “concentration camps” that over time held as many as 115,000 people, mostly women and children. Almost 28,000 died, including 22,000 children — 10 percent of the Boer population. Approximately 20,000 blacks also died in camps. The appalling toll sparked international outrage. Irish nationalists sympathized with the embattled Boers, and sympathy surely spread in the United States, where the plucky Boers taking on the Redcoats kindled memories of the revolutionary wa

This “stamp,” or Cinderella label, at left is quite a puzzler. (The image is from the Internet.) It pays tribute to Paul Kruger — in Spanish and Latin. (“Glory to Kruger — The Transvaal for the Boers”) The best I can figure is that this was a propaganda label put out around the time of the Second Boer War. A number of settlers from the Transvaal had relocated to Argentina. There they formed a close-knit farming community and outpost that has lasted to this day.

This “stamp,” or Cinderella label, at left is quite a puzzler. (The image is from the Internet.) It pays tribute to Paul Kruger — in Spanish and Latin. (“Glory to Kruger — The Transvaal for the Boers”) The best I can figure is that this was a propaganda label put out around the time of the Second Boer War. A number of settlers from the Transvaal had relocated to Argentina. There they formed a close-knit farming community and outpost that has lasted to this day.

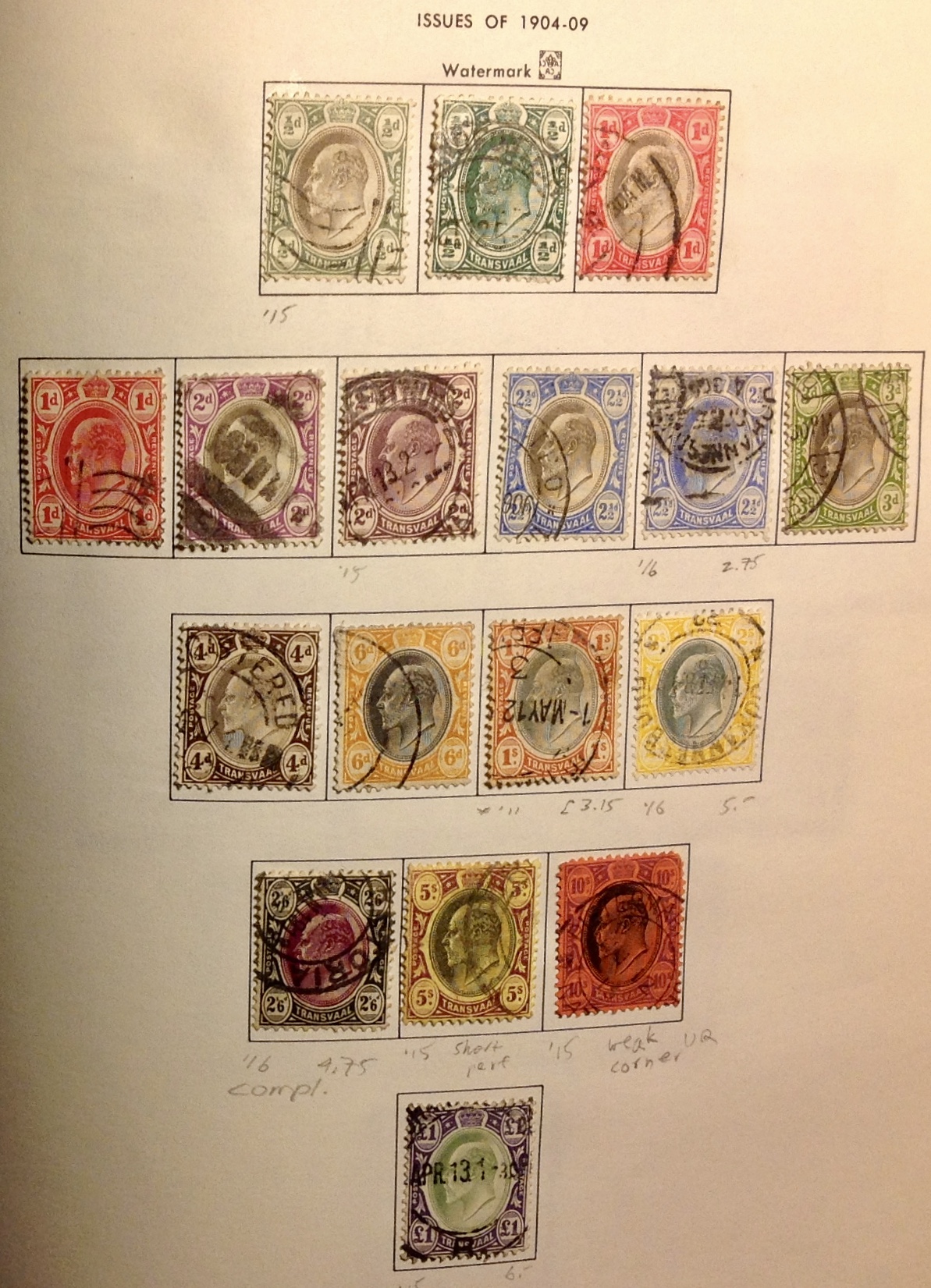

I include this set from my collection (above and right) just to show off. It’s the second Edward VII set, issued shortly before his death and the creation of the Union of South Africa in 1910. The set catalogs at about $30, so it’s not rare. It’s neat to have a complete set, though, don’t you think? As you can tell from my notations, it took me more than nine years to assemble it — patience is a virtue for stamp-collectors. Filling out sets over time is one of the deep, glacial satisfactions of the hobby. Reaching completeness is soul-satisfying. Besides, these stamps have a certain elegance, and the contrasting color combinations are gorgeous, don’t you think?

Smuts is second from the left in this line-up of South African presidents. South Africa almost never put a black face on a stamp until after Nelson Mandela became president in 1994.

Jan Smuts strengthened the Boers’ position in early 1902 by seizing the copper mining town of Okiep, demonstrating Afrikaner resolve. Although the Boers’ way of life would be forever changed, the negotiated peace protected their rights in Transvaal. The Boers would become full partners in the future Union of South Africa (at the expense of black South Africans). Smuts, Kruger’s brilliant protege, would go on to help found a political party for the Boers, and serve as South Africa’s prime minister for two long stints (1919-24, 1939-48).

THERE’S MORE TO SAY (SEE PART 3, IN THE WORKS)

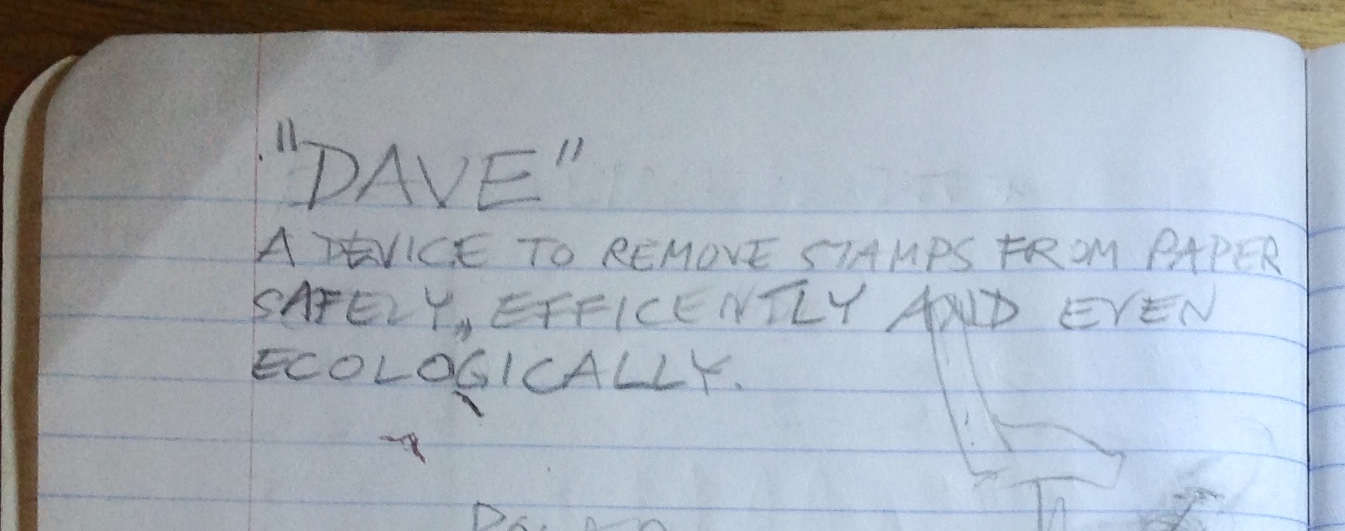

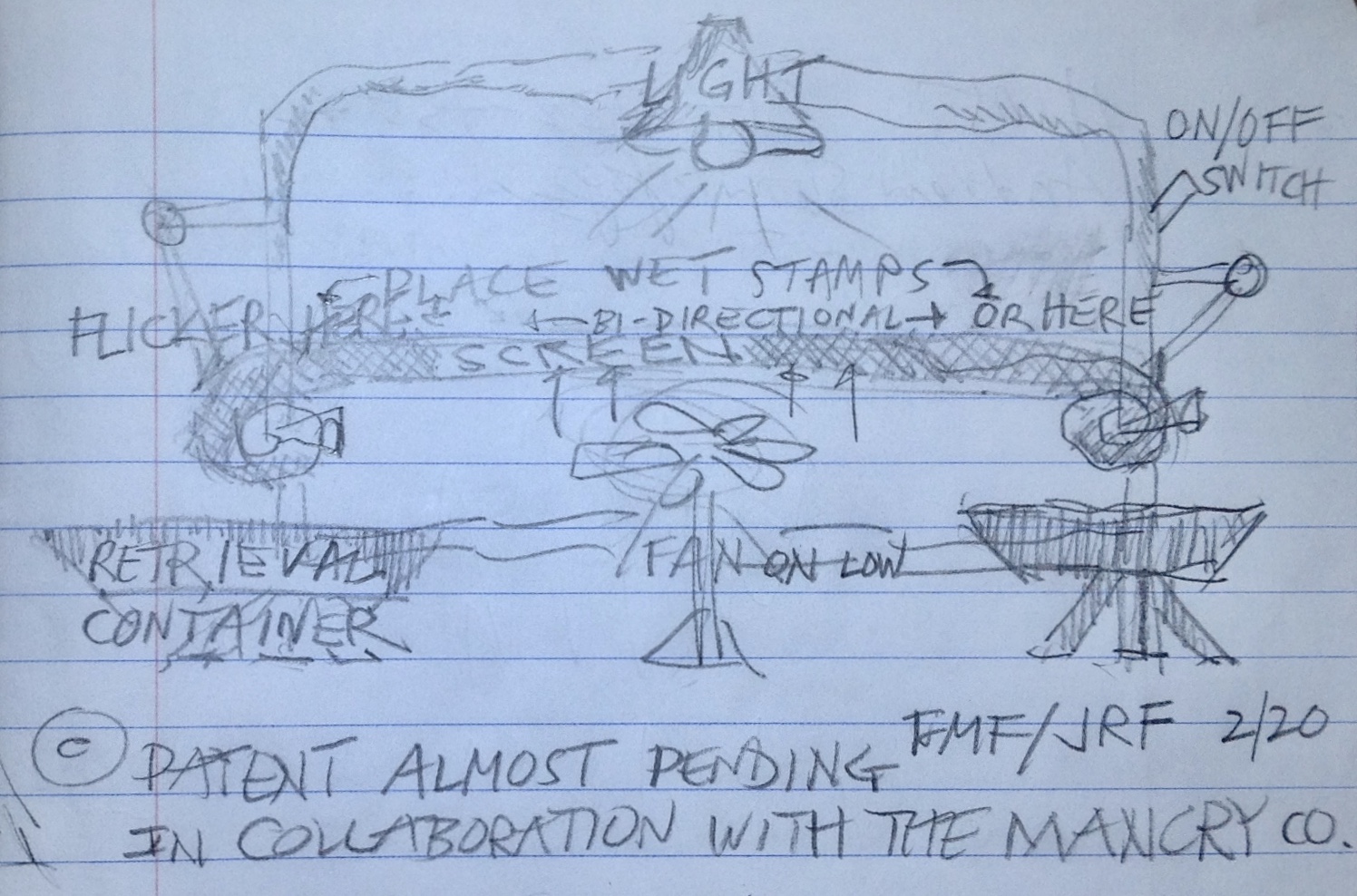

BONUS: Stamp collecting during the Covid19 shutdown, or: Philatelic phun in the pandemic

Stamp collectors know that theirs is not an intensely social hobby. True, there are stamp clubs, stamp shows, exhibitions and visits to the post office. Trading stamps — one of the most basic pastimes of philatelists — necessarily requires that you have at least one counterpart to haggle and bargain and carry on with. Yet much of the time it’s just you and your stamps.

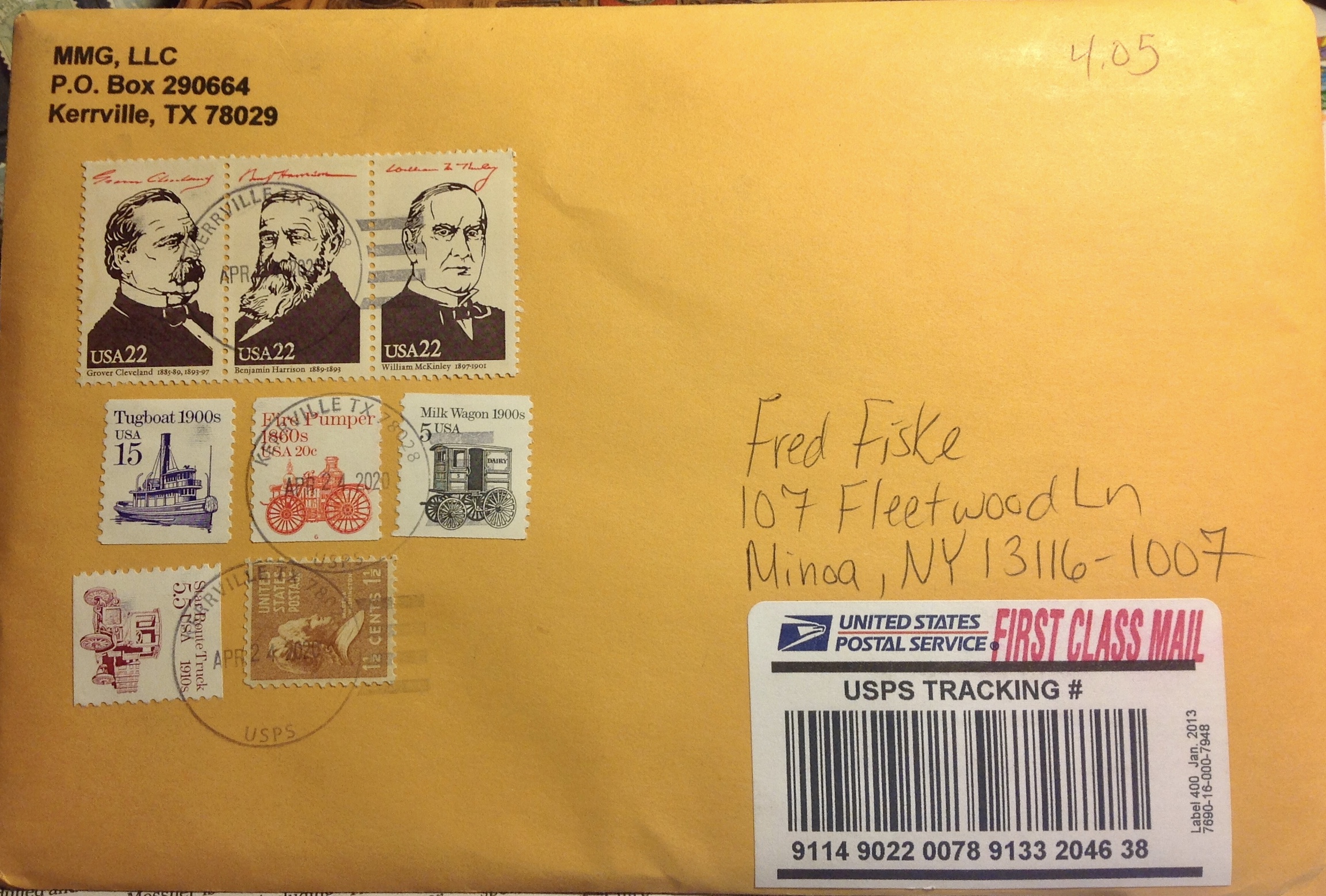

Sorting stamps, arranging stamps, mounting stamps, reviewing them with pleasure and satisfaction in their colorful, orderly, venerable rows — all these are by nature solitary activities that can be pursued happily under quarantine. Today’s stamp collector who is active in the thrilling world of online sales and auctions, is also pursuing this pleasure all by himself (or herself). Yes, you are negotiating with a dealer or private seller, but usually at a safe remove — across the country or somewhere else in the world. When the envelopes containing stamps arrive in your mailbox, you are pretty much on your own in admiring the thick little packages,

Just look at the selection of collectible stamps arrayed on both sides of this envelope one seller mailed to me in April.

often festooned with an exotic array of fractional postage stamps affixed by playful or well-supplied dealers and sellers. Certainly my spouse has no interest in this mail, or in any other aspect of my hobby really. Most of the time she tolerantly leaves me alone to indulge my

philatelic proclivities, only occasionally sighing or intervening when my spending habits start to deplete the family treasury.

philatelic proclivities, only occasionally sighing or intervening when my spending habits start to deplete the family treasury.

For these reasons, there is no reason why something as terrifying, isolating and bothersome as a Covid19 epidemic should interfere with a stamp collector’s happy hobby.

Sure, I miss my biweekly meetings of the Syracuse Stamp Club in the basement of the Reformed Church. I miss the diverse lot of stamp collectors who show up with their quirky personalities, peculiar collecting habits, interesting stories, strong opinions, good humor, enlightening programs and intriguing stamps to sell or trade. Our monthly auctions are exciting to collectors like myself. You can pick up some unbelievable bargains, often for no more than “a buck.” I look forward to the resumption of club meetings.

Recently Larry, our club VP, invited members to write short essays on “How I Spent My Covid19 Vacation,” with particular emphasis on stamps. It’s a fun idea, and it was the spark that ignited this little essay. I’ve also been thinking of other ways to stay engaged with the stamp club. For example, how about a Zoom meeting where one or more of us sits in our study, displaying prized stamps from our collections? It’s something we can do in this time of isolation that we normally wouldn’t when gathered together as a group. Maybe we can save that one for the next epidemic.

Family expenses of late have limited the discretionary cash available to spend on stamps. That changed after wife Chris and I received our double dose of Covid stimulus checks, or whatever they are called. The sudden influx of $2,400 was quite a windfall, particularly since we retirees weren’t in financial need. After making large donations to the Central New York Food Bank and our church’s Ministerial Discretionary Fund, there was still plenty left for me to satisfy my philatelic phishing impulses. So I cast out my line into the cyber-sea and came up with some beauties.

As my intimates know, I maintain a stamp blog with monthly posts that I hope are of interest to the general reader, not just the avid or casual philatelist. (To sample the blog, search “FMF Stamp Project.”) By the way, the blog is another solitary activity unaffected by the epidemic. As I compose my monthly posts, which generally touch on stories about my own collection, I use them as an excuse to scan the online market for stamps to fill gaps in sets that are under review. Lately I have enriched my Natal and Transvaal collections as I explore the postal history of southern, eastern and central British Africa. As I shop and buy online, one thing leads to another and my attention inevitably wanders to stamps from other countries, usually early British Africa, Europe or America.

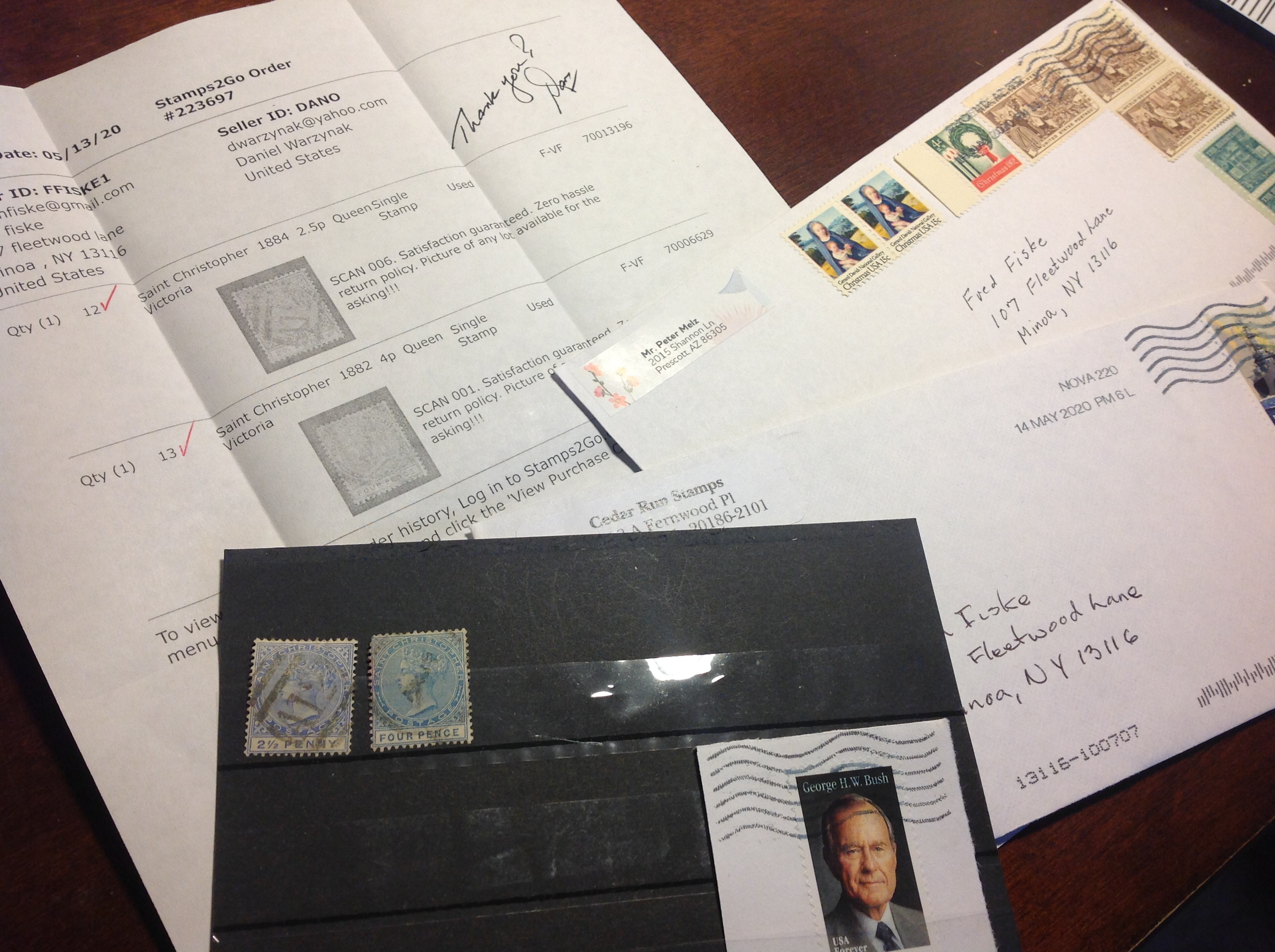

Today, for example, three envelopes greeted me in the mailbox — from Arizona, Virginia and Washington State. Oh joy! They contained 19th century, Victorian-era

Here are two of the envelopes I received today, along with the contents of a third, already opened.

stamps from St. Christopher, Grenada, St. Vincent, Trinidad, and Trinidad and Tobago. The task of opening the envelopes, examining, sorting and arranging the stamps, mounting them in my album, filling gaps , adding appropriate notations, is a delicious prospect indeed — not dependent on either the presence or absence of Covid19.

As you can see here, I have gotten as far as arranging my precious new acquisitions on a stock card. Some of the stamps date back to the 1860s. I paid $70 to three sellers for all of them.

Some might raise the question of viral risk concerning these envelopes arriving from all over. Could they be contaminated? To which I reply: not bloody likely. Though there are lugubrious guidelines about how long the virus can survive on paper, plastic and the rest, I have never heard of anyone contracting the virus from handling stamps. Until I hear otherwise, I’m not worrying about it. Aren’t there enough other things to worry about? **

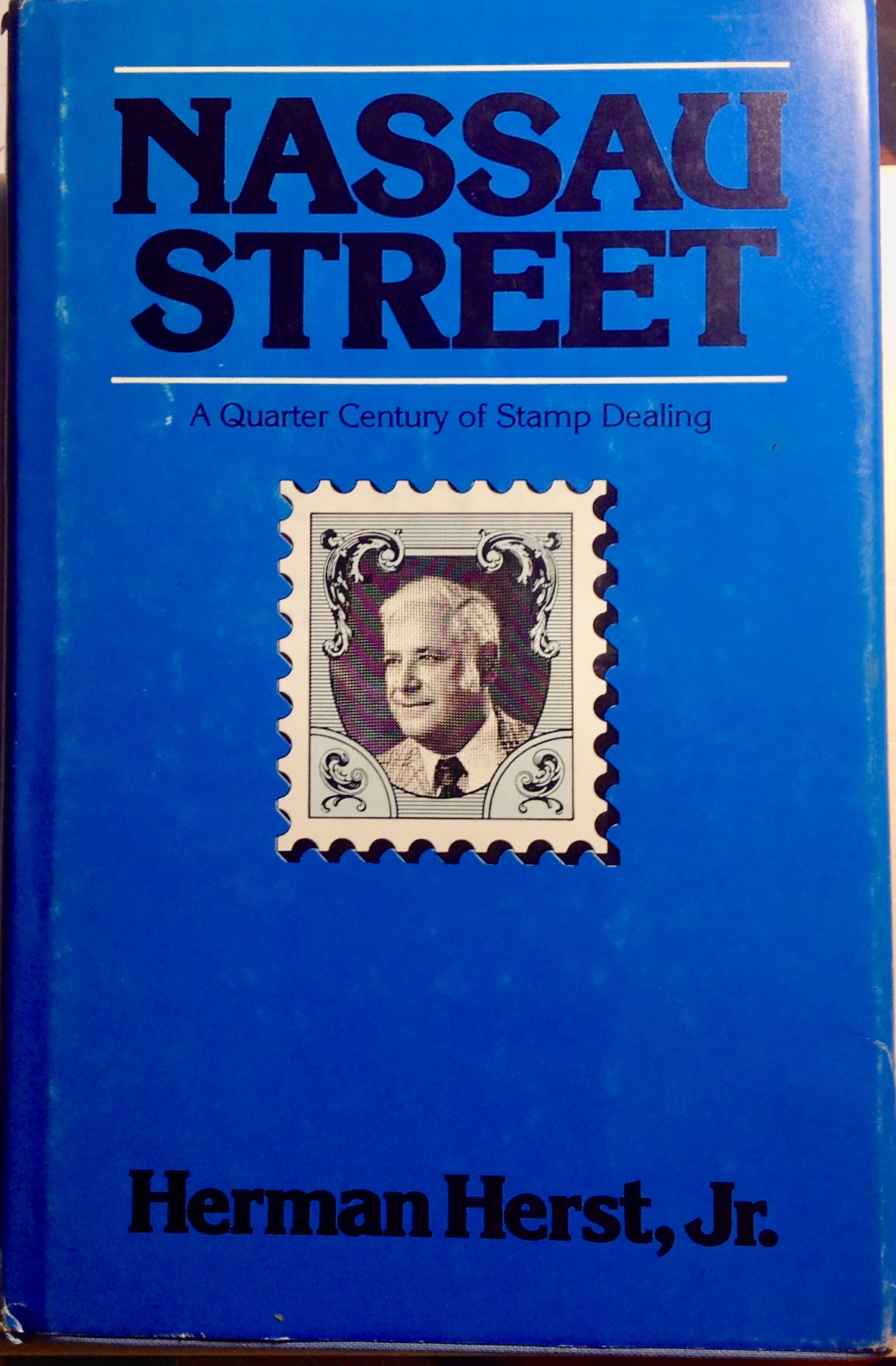

My buddy George, a San Francisco lawyer and on-again, off-again stamp collector, recently sent me two copies of the classic stamp-collecting book, “Nassau Street: A  Quarter Century of Stamp Dealing,” by Herman Herst Jr. One copy was a signed first edition, the other a standard hardcover reprint. (I think George just wanted to get them out of the house.) I started reading, and it’s quite an eye-opener. (Hey — this is something else you can do during the Covid19 shutdown: read about stamps!) While I haven’t gotten very far, I would like to share a glimpse of the high-energy world that stamp collecting used to be. In the mid-1930s, the Stamp Center Building at 116 Nassau St. in Manhattan housed 40 stamp dealers. That didn’t include other dealers ranged up and down the block. I remember my old Pa, an enthusiastic collector, loved making solo side trips to “Nassau Street” during our infrequent family visits to New York City in the 1950s. I was too young to get much exposure to that zesty, colorful arena of stamp collecting in its heyday. I do remember, however, a couple of visits to Gimbel’s department store in the 1960s, where I mooned over the displays at the stamp counter.

Quarter Century of Stamp Dealing,” by Herman Herst Jr. One copy was a signed first edition, the other a standard hardcover reprint. (I think George just wanted to get them out of the house.) I started reading, and it’s quite an eye-opener. (Hey — this is something else you can do during the Covid19 shutdown: read about stamps!) While I haven’t gotten very far, I would like to share a glimpse of the high-energy world that stamp collecting used to be. In the mid-1930s, the Stamp Center Building at 116 Nassau St. in Manhattan housed 40 stamp dealers. That didn’t include other dealers ranged up and down the block. I remember my old Pa, an enthusiastic collector, loved making solo side trips to “Nassau Street” during our infrequent family visits to New York City in the 1950s. I was too young to get much exposure to that zesty, colorful arena of stamp collecting in its heyday. I do remember, however, a couple of visits to Gimbel’s department store in the 1960s, where I mooned over the displays at the stamp counter.

There were stamp magazines of many varieties starting in the 1930s — Mekeel’s, Philatelic Gossip, Linn’s, Stamps, International Stamp Review, Stamp News, Kaw Chief Stamp Journal, Chambers Stamp Journal, Stamp Land. “It seemed that everyone who ever collected stamps and had a printing press was publishing a stamp magazine,” Herst wrote. One of them, Western Stamp Collecting, became so popular it started publishing twice a week, up to 16 broadsheet pages, “and in the process developed the largest circulation a newspaper had ever experienced,” Herst claimed.

Stamp clubs, back then, were wildly popular. “Every night in the week you could attend a stamp club in New York,” wrote Herst. “Each week The Sun would chronicle the founding of a new club. … The Bronx County Stamp Club was the largest club of all. Seldom did less than 150 members show up for a meeting. It occupied extensive rented quarters in Vasa Temple, a lodge meeting hall, at 149th Street and Third Avenue in the Bronx. It is safe to say that nowhere in the stamp world was more business transacted in a three-hour period than at the Bronx Club. …”

Those were the days, eh? Stamp collecting sounds like quite a sport back then, doesn’t it? Very different from the rather moribund affair of today. Imagine what Covid19 would have done to the strenuously interactive stamp business of the 1930s!

Philately may be a comparatively quiet enterprise today, but it is not extinct. As stamp collectors know, the Internet has infused new life into the hobby, stabilizing values and stimulating demand. The future may not bring a return to the halcyon days of “Nassau Street,” but at least there is a future. Because of the nature of philately, there is no reason to fear that the current Covid19 unpleasantness will change any of that.

** NOTE: Regarding contamination and stamps, this email arrived in my box today from a stamp dealer, who is either from the Philippines or has many customers living there, under the heading, “Corona Virus and Philippine Post”:

Dear customer, … I know some of you have received some orders but not all. I was talking to our Post Office staff again yesterday when I delivered the recent orders for mailing. They advised that Philippine Post is not processing international mail again — no reason given. This is all very frustrating for you I realise and I thank you for your patience. Your orders will arrive eventually. …

THE END

ZAR/Transvaal: The Story Begins

EDITOR’S NOTE: The third stamp-issuing authority in British South and Central-East Africa, in 1869 (after Cape of Good Hope in 1853 and Natal in 1857) was not in British territory. The ZAR — Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek — was into its 14h year as an independent Boer republic. Today there is no map reference to the ZAR, or Transvaal. Much of the high veld territory comprises the province of Gauteng in the Republic of South Africa. The postal history of ZAR/Transvaal is such a rollicking tale that it will take three installments to get it all out …

EDITOR’S NOTE: The third stamp-issuing authority in British South and Central-East Africa, in 1869 (after Cape of Good Hope in 1853 and Natal in 1857) was not in British territory. The ZAR — Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek — was into its 14h year as an independent Boer republic. Today there is no map reference to the ZAR, or Transvaal. Much of the high veld territory comprises the province of Gauteng in the Republic of South Africa. The postal history of ZAR/Transvaal is such a rollicking tale that it will take three installments to get it all out …

The ZAR was a loose but durable association of Boer farmers and other settlers who trekked or otherwise made their way beyond the Cape Colony, beyond the Orange Free State (another Boer republic), beyond British Natal, across the Vaal River  intothe tribal frontier. “Trans-Vaal,” or Transvaal, is another name for the territory that became a battleground between imperial Britain and the indigenous “tribe” of Boers. When the fighting was over in 1902, the carnage was considerable. The Boer death toll was about 25,000, while the British lost 22,000; 12,000 blacks also perished. Politically, the biggest losers were the indigenous blacks, as Boers and Brits joined forces and in 1910 formed the white supremacist Union of South Africa.

intothe tribal frontier. “Trans-Vaal,” or Transvaal, is another name for the territory that became a battleground between imperial Britain and the indigenous “tribe” of Boers. When the fighting was over in 1902, the carnage was considerable. The Boer death toll was about 25,000, while the British lost 22,000; 12,000 blacks also perished. Politically, the biggest losers were the indigenous blacks, as Boers and Brits joined forces and in 1910 formed the white supremacist Union of South Africa.

For the Boer pioneers back in the 1830s, the fertile plain of southern Africa was a vision of milk and honey. You can hear it, practically taste it in the Boer mantra of  the sweet life — lekker lewe. The settlers did make for themselves a good life in Africa. A typical Boer head of household would be self-reliant, simple and practical in his daily life; deeply religious, loyal to kith and kin; a resourceful frontiersman; a shrewd negotiator; a robust “family man” with many children (see right). The Boers were successful farmers and ranchers. They thrived in the seemingly endless supply of arable land and grazing grasses, and took maximum advantage of the indigenous population as cheap labor.

the sweet life — lekker lewe. The settlers did make for themselves a good life in Africa. A typical Boer head of household would be self-reliant, simple and practical in his daily life; deeply religious, loyal to kith and kin; a resourceful frontiersman; a shrewd negotiator; a robust “family man” with many children (see right). The Boers were successful farmers and ranchers. They thrived in the seemingly endless supply of arable land and grazing grasses, and took maximum advantage of the indigenous population as cheap labor.

Were the Boers racist? Yes by today’s standards, though during the 1700s and 1800s they did not treat indigenous blacks more harshly than other societies. Great Britain’s abolition of slavery in the colonies in 1833 helped precipitate a migration of Boers beyond the reach of Cape Colony law and the British Crown. The Boers as a rule were not sadists or tyrants, but they never countenanced equal rights for blacks, as Natal preached and the Cape Colony actually practiced for a while. The Boers trained primitive Bushmen for domestic service, in cahoots with the British, some of whom honored equality as much in the breach as the observance. Early trainees among the Bushmen and “Hottentots” became Fingoes, skilled fighters, guides and scouts. The Boers claimed that their system of indenture was not really slavery, but their constitutions never allowed blacks to become citizens — unlike the Cape Colony, which enshrined equal rights for all property owners from the 1830s to the  1870s. The Boer leader Jan Smuts (1870-1950), who helped create what became the Union of South Africa, grew up working side by side with blacks as a farmhand and cowherd. Though he endorsed the racist Boer hierarchy until nearly the end of his life, Smuts also respected tribal ways, which he saw eroded by the Cape Colony’s efforts in earlier decades to establish equality between blacks and whites. “The old practice mixed up black with white in the same institutions,” he wrote, “and nothing else was possible after the native institutions and traditions had been carelessly or deliberately destroyed.”

1870s. The Boer leader Jan Smuts (1870-1950), who helped create what became the Union of South Africa, grew up working side by side with blacks as a farmhand and cowherd. Though he endorsed the racist Boer hierarchy until nearly the end of his life, Smuts also respected tribal ways, which he saw eroded by the Cape Colony’s efforts in earlier decades to establish equality between blacks and whites. “The old practice mixed up black with white in the same institutions,” he wrote, “and nothing else was possible after the native institutions and traditions had been carelessly or deliberately destroyed.”

Among the early trekkers was Paul Kruger. Born in the eastern Cape Colony in 1825, he relocated with his family as a child in 1836. Kruger would become leader of the ZAR, an embodiment of Boer values: stubborn, proud, clinging to the Bible to the bitter end. As early as the 1840s, many Boers considered themselves an indigenous African people. They traced their ancestry to the likes of

Among the early trekkers was Paul Kruger. Born in the eastern Cape Colony in 1825, he relocated with his family as a child in 1836. Kruger would become leader of the ZAR, an embodiment of Boer values: stubborn, proud, clinging to the Bible to the bitter end. As early as the 1840s, many Boers considered themselves an indigenous African people. They traced their ancestry to the likes of

That’s van Riebeeck (1619-1677) on the right. To the left is his wife, Maria (1629-1664). Originally from a family of French Huguenots, Maria has been revered as the ancestral “mother” of the Afrikaners. She reportedly was a charming hostess and an able diplomatic companion to her husband; she also was involved in finance and indigenous relations.

Jan van Riebeeck, who settled Capetown in 1652. Their forebears were pilgrims and pioneers, much like those in the “new world” of America. Two hundred years later, the Boers were as much a tribe as the Zulu, the Tswana or the Swazis …

The Boers’ orneriness and independent streak hindered their ability to self-govern. Their burgeoning families and communal settlements were so self-sufficient and zealous in their pursuit of the lekker lewe that they had trouble trusting outside authority and ceding their individual autonomy to a government entity — not to mention paying taxes. This clannish  chauvinism led to all kinds of administrative and political problems through the years, not only in the ZAR, but in the neighboring Orange Free State and in smaller enclaves like Stellaland, Lijdenburg, Utrecht and Goosen (Goshen).

chauvinism led to all kinds of administrative and political problems through the years, not only in the ZAR, but in the neighboring Orange Free State and in smaller enclaves like Stellaland, Lijdenburg, Utrecht and Goosen (Goshen).

The Boers’ strengths lay in their resourcefulness, industry, productivity, faith in God and loyalty to family and clan. They were effective fighters when called upon to defend hearth and home, but less successful as an organized army and bureaucracy. Their assembly or Volksraad was short of cash and long on argument, and struggled to maintain its mandate; besides, everyone had a farm to run.

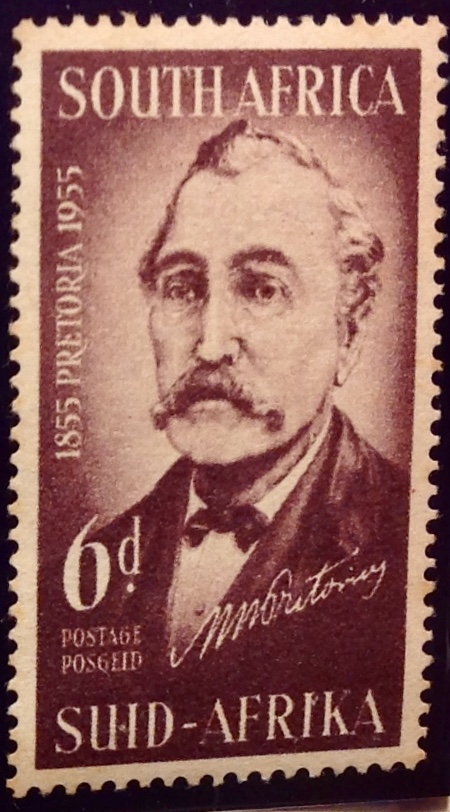

Notice how this philatelic tribute to Andries Pretorious has to be on two separate stamps, one in English, the other in Afrikaans. It’s an odd doppel entity, which was embodied in South African stamps for decades. FYI, the flag is from Pretorius’s short-lived Boer Republic of Natalia. “Reaffirmation of the vow” refers to Boer aspirations, translated as “Werbevestiging van die Gelofte.”

Andries Pretorius (1793-1853) was instrumental in the creation of the ZAR, though he died just as his dream was about to materialize. Tall and barrel-chested, his was a commanding presence. He led the Boers in battles against indigenous rivals — allying with one tribal king against another, slaughtering great numbers of Zulus while suffering few

Though Martinhus Pretorius led the Orange Free State and was ZAR’s first president, he never seemed to live up to the standards of his famous father Andries. Notice the family resemblance — the same sad eyes, the same long face and strong chin.

casualties on his side. His republic of Natalia was short-lived, displaced by British Natal. Pretorius pushed north as the British grew more entrenched, and with allies including the young Paul Kruger, he began working on the outlines of a new republic across the Vaal River. First the Boers had to defend themselves. They bested the British in bloody skirmishes, most notably the Battle of Blood River. The Sand River Convention in 1852 ended what became known as the First Boer War, with casualties in the hundreds, not thousands. Britain signed treaties recognizing the Orange Free State in 1854, and two years later acknowledged the independence of

the roughly 40,000 Boers who had settled north of the Vaal River. Andries Pretorius’s son Martinhus became the ZAR’s first president, with Pretoria as his capital, named in his father’s honor.

In ensuing years, Paul Kruger emerged as the ZAR’s strongest leader. The Boers built a dynamic, self-sufficient society, yet faced constant pressure from displaced tribes, as well as from English settlers and business interests. These “uitlanders” chafed at a ZAR constitution whose long residency requirements curtailed their political rights. The ZAR also suffered because so many of its own Boer constituents resisted strong central authority of any kind.