Although I am not a “topical” stamp collector, there is one “topic” I have a soft spot for — stamps on stamps. For some reason, the framing of a stamp-within-a-stamp holds special appeal to me, like a trompe l’oeil painting by William Hartnett — a philatelic diorama; not to mention that the reproductions of early stamps are usually very fine on these commemorative issues. I have quite a few of these stamp-on-stamp issues, and would be glad to share them in a post if you wish.

Although I am not a “topical” stamp collector, there is one “topic” I have a soft spot for — stamps on stamps. For some reason, the framing of a stamp-within-a-stamp holds special appeal to me, like a trompe l’oeil painting by William Hartnett — a philatelic diorama; not to mention that the reproductions of early stamps are usually very fine on these commemorative issues. I have quite a few of these stamp-on-stamp issues, and would be glad to share them in a post if you wish.

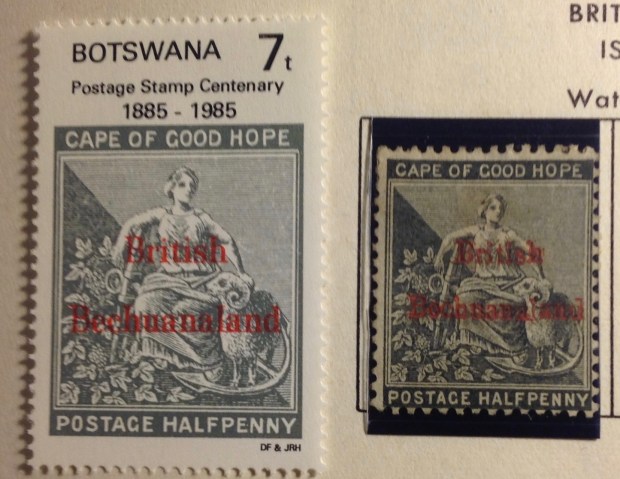

At right is one stamp-on-stamp from the southern African nation of Botswana. Issued in 1985, it commemorates a century of postage stamps — though the region was called Bechuanaland in 1885. I’m struck by the decision of postal authorities in the sovereign state of Botswana, which gained it independence from Great Britain in 1966, to issue these stamps at all. Stamps appearing in this set were put out during the years when the area known as Bechuanaland was part of the British Empire. Were the tensions of post-colonialism over by 1985? Was all forgiven between Motswana (the name for Botswana citizens) and their former colonial rulers? Were there nostalgic anglophiles in the post office who still valued British tradition? Or were they exercising a fine sense of irony, reprinting these emblems of colonial subjugation with a wink and a nod, with the proud banner of “Botswana” emblazoned at the top?

Such speculation may be idle, but it’s just the thing to amuse stamp collectors. In this short post, profusely illustrated as usual, my plan is to have some more fun with these stamps on stamps. I also must provide as background a short course on the interesting history of Botswana/Bechuanaland across the century prior to 1985. Finally, I expect I will have to share with you my impressions of why Botswana has sustained a relatively sturdy democracy in its first half-century of independence — an anomaly in sub-Saharan Africa.

… All this, by way of circling back to what will follow: a review of my Bechuanaland stamp collection, continuing my British Africa stamp review that was interrupted so long ago, after Basutoland/Lesotho. It’s all riveting stuff. On to Bechuanaland!

By the 1880s, the swashbuckling imperialist Cecil Rhodes was clamoring for the Cape Colony to claim dominion over the arid plains to the north known as Bechuanaland. In 1883 he made his case to “Grandmama,” his irreverent nickname for the Victorian home government. He invoked the shades of Livingstone and Moffat and their missionary roads of past decades. The path north could be the “Suez Canal” of trade to the interior, Rhodes argued. But Gov. Scanlen of Cape Colony demurred, dismissing the sparsely populated region as mostly desert, ruled by squabbling chiefs — in short, not worth the effort.

Still, imperial authorities in London were uneasy. Boer freebooters were streaming across the border of the Orange Free State, seeking new pastures and opportunities in what there was of a Bechuanaland veld. The neighboring Ndebele tribe also had aggressive territorial designs on its longtime Tswana rivals. In 1885, Sir Charles Warren left the Cape Colony with 4,000 imperial troops. As he moved north, he signed treaties of protection with local chiefs. Among them was the remarkable Tswana leader, King Khama III.

Khama rightfully deserves a biography of his own — indeed, the first account of his life was written in the 1880s, when the king and his entourage visited London to lobby for British protection from the Boers, the Ndebele and expansionists like Rhodes. Khama enjoyed an audience with the queen, and drew enthusiastic crowds at receptions sponsored by evangelical groups who applauded Khama’s conversion to Christianity and promotion of “civilized” values like education, modernization and monogamy.

Khama rightfully deserves a biography of his own — indeed, the first account of his life was written in the 1880s, when the king and his entourage visited London to lobby for British protection from the Boers, the Ndebele and expansionists like Rhodes. Khama enjoyed an audience with the queen, and drew enthusiastic crowds at receptions sponsored by evangelical groups who applauded Khama’s conversion to Christianity and promotion of “civilized” values like education, modernization and monogamy.

Khama had become king in 1875, after prevailing in power struggles between tribes and family members that included three assassination attempts and a fateful dispute over a lost cow. He earned his title, Khama (the Good) by his far-sighted policies, which included consolidating and expanding his sparsely populated territory, fostering trade with all comers, and promoting up-to-date farm techniques. He was particularly adept at blending traditional practices with western innovation — for example, using the voluntary labor of tribal mephato contingents to build schools, silos and irrigation systems.

Khama was a charming, charismatic leader and an effective, multilingual diplomat. He prevailed in the climactic confrontation with would-be usurpers on his borders.

Above is a map of Bechuanaland before 1885, surrounded by variously covetous neighbors like the Germans to the west, the Cape Colony, Boers from the Orange Free State and Transvaal, as well as smaller state-lets like Stellaland, Griqualand West and East, and the Orange Free State. The map below shows how the crown colony of British Bechuanaland (all pink) in 1885 was carved out of the larger Bechuanaland Proectorate (outlined in pink).. The crown colony incorporated smaller states into what would become provinces of South Africa.

The deal reached in 1885 created the Bechuanaland Protectorate, under direct imperial supervision, shielding the lands of King Khama from schemers and squatters in the Transvaal and the Cape Colony as well as the Ndebele and other hostiles.

The southern region of Bechuanaland, meanwhile, became British Bechuanaland, a crown colony. By and by, that southern portion was absorbed by the Cape Colony, then joined the Union of South Africa in 1910. As the years passed, pressure continued to turn over the protectorate to  South Africa or Rhodesia. But Khama and his colonial protectors would have none of it. Thus it was that Bechuanaland Protectorate was spared the blight of apartheid that settled on South Africa after 1948. Those living in the southern portion of the Tswana ancestral lands eventually were consigned to the hollow South African “homeland” of Bophutatswana, one of the last concoctions of the apartheid state in the years before Nelson Mandela ushered in the new South Africa in 1994.

South Africa or Rhodesia. But Khama and his colonial protectors would have none of it. Thus it was that Bechuanaland Protectorate was spared the blight of apartheid that settled on South Africa after 1948. Those living in the southern portion of the Tswana ancestral lands eventually were consigned to the hollow South African “homeland” of Bophutatswana, one of the last concoctions of the apartheid state in the years before Nelson Mandela ushered in the new South Africa in 1994.

Bechuanaland changed its shape over the years before becoming Botswana, as you can see by comparisons with the current map, above.

In its early years, Bechuanaland Protectorate was largely self-governed; the British ruled with a light hand. In the 1890s, however, local sovereignty was curtailed as colonial officials took over administration of the territory. The protectorate did not escape the racial discrimination and economic exploitation endemic to colonialism.

(Text continues after illustrations and captions.)

Above left is the real stamp of 1897, from my collection. On the right is the image on a stamp from Botswana, issued in 1985 to commemorate a century of postage stamps in the region. Below are images of a British Bechuanaland stamp. I think it’s fun to compare the real thing and the image, don’t you? Early issues from both regions were overprinted stamps from Great Britain and the Cape of Good Hope (a/k/a the Cape Colony). Bechuanaland Protectorate issued stamps from 1888 until Botswana’s independence in 1966. Stamps from British Bechuanaland first appeared in 1886, according to the Scott catalogue. British Bechuanaland was annexed by the Cape Colony in 1897.

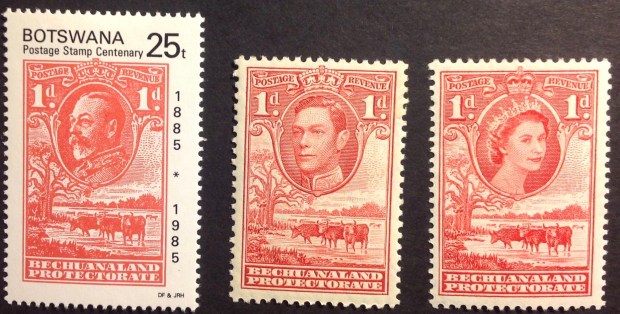

The first original stamps of Bechuanaland Protectorate, in 1932, feature a charming engraving of grazing cattle. British King George V, in a three-quarters portrait, gazes out regally and benignly. He is near the end of his reign. It seems the set was such a hit that postal authorities kept the vignette and design for the next two monarchs, simply substituting portraits of George VI and Elizabeth II (see below — does it strike you, as it does me, that the stamp featuring Elizabeth looks more modern than the one with either George?).

I checked in my collection and discovered that the 1965 stamp (top) has eluded me so far. (It’s not expensive.) Issued a year before independence, it commemorates “internal self-government.” The name has been shortened, dropping “Protectorate.” The portrait of the queen is there. So philatelically speaking, the nation of British Bechuanaland came back to life in 1965, from its demise in 1897. Of course, that’s just a stamp story. Months later, the independent nation of Botswana was born. The other stamp illustrated here depicts the “National Assembly Building” in Gaborone. It looks like quite a 1960s-modern monstrosity, but that’s just one critic’s opinion. I was curious, however, to see how the National Assembly Building has held up over the past 50 years. Is it still standing? Has it been replaced? Expanded? Thanks to the web and Google Earth, I got some answers (see photos below).

Above is a view of the columns, courtesy of the Internet. Below is a Google Earth image of the National Assembly Building, seen from a brick plaza. It looks well-maintained and accessible — but not quite like the rendering on the stamp! The stamp doesn’t show a tower, or a large central arch. Was that image in 1966 just an architect’s rendering? If so, shouldn’t it have been labeled as such? Tut! tut!

The protectorate’s economic dependence on South Africa was underscored by the fact that its governing institutions were located in Mafikeng, south of the border. (The capital is now Gaborene, within Botswana.) King Khama died in 1923, and was succeeded by kinsmen. After achieving independence in 1966, Botswana’s voters have elected and re-elected Khama’s descendants. Its first president, Seretse Khama, was a legitimate Ngwato heir; his son, Ian Khama, was elected in 2008.

This is a remarkable, inspiring tale — how more than a century ago, a strong African leader forged a nation that survived decades of colonial interference to emerge as a rare success story in Africa. There is no denying the skill with which King Khama in the 1880s maneuvered among the likes of Queen Victoria and Whitehall, Cecil Rhodes, Boer squatters, rival tribesmen and hostile Ndebele. Also impressive was the record of independent Botswana’s first rulers — Seretse Khama, then Quett Masire — who had to maneuver among the quarreling factions of Rhodesia, South Africa, Angola and other troubled neighbors. That Botswana’s fairly elected leaders kept their nation at peace, with a sound and growing economy and a minimum of corruption, seems nearly a miracle.

There is a fairy tale quality to the story as well — how in 1948 Seretse Khama, then a dashing young law student and tribal prince in London, met Ruth Williams, a white English girl. The couple fell in love. After several months Khama proposed and Ruth accepted. There was a predictable uproar over this

There is a fairy tale quality to the story as well — how in 1948 Seretse Khama, then a dashing young law student and tribal prince in London, met Ruth Williams, a white English girl. The couple fell in love. After several months Khama proposed and Ruth accepted. There was a predictable uproar over this  interracial courtship — from the church, from the colony, from the tribe. Just about everyone was against the marriage — except Ruth and Khama. The butt-inskis even persuaded the vicar to cancel the ceremony on the morning of the wedding — but the good cleric reportedly found a way to sneak it in after an ordination ceremony at the cathedral later the same day. Khama then faced the combined wrath of peers and mentors. “I still want to be your chief,” he told his people. He also declared: “I cannot leave her.” The couple was compelled to live in exile for six years (in England, naturally). Eventually Khama and his bride were allowed home — after he renounced his throne. He arrived to a hero’s welcome in 1956. Kwama was elected Botswana’s first president in 1966, and served with distinction for more than three terms. The couple had four children. Sir Seretse Khama died in 1980, Dame Khama in 2002. Their romantic saga unfolds n the movie, “A United Kingdom,” released in 2016.

interracial courtship — from the church, from the colony, from the tribe. Just about everyone was against the marriage — except Ruth and Khama. The butt-inskis even persuaded the vicar to cancel the ceremony on the morning of the wedding — but the good cleric reportedly found a way to sneak it in after an ordination ceremony at the cathedral later the same day. Khama then faced the combined wrath of peers and mentors. “I still want to be your chief,” he told his people. He also declared: “I cannot leave her.” The couple was compelled to live in exile for six years (in England, naturally). Eventually Khama and his bride were allowed home — after he renounced his throne. He arrived to a hero’s welcome in 1956. Kwama was elected Botswana’s first president in 1966, and served with distinction for more than three terms. The couple had four children. Sir Seretse Khama died in 1980, Dame Khama in 2002. Their romantic saga unfolds n the movie, “A United Kingdom,” released in 2016.

Post-script to this anecdote: Seretse and Ruth Khama’s son, Khama Ian Khama, was elected president of Botswana in 2008 and had a successful 10-year presidency. Some day this biracial president-son may be known as Africa’s Obama; or will the former  U.S. president — also the son of an interracial couple — be remembered as America’s Khama?

U.S. president — also the son of an interracial couple — be remembered as America’s Khama?

For more than a half-century, the Republic of Botswana has been a model government in Africa, successfully blending democratic practice with respect for tribal ways. It has not seen coups or civil war, and enjoys a relatively robust tourism industry. Per capita yearly income of more than $18,000 is near the top for the continent. Granted, there are only two million people in a nation the size of France; a nation, moreover, blessed with rich deposits of diamonds. Botswana has the lowest corruption ranking in Africa, and the highest rating in human development indices. Botswana’s leaders have broken ranks with their peers in speaking out against corruption and abuses in Zimbabwe, Sudan and elsewhere. While Botswana benefits from certain anomalies, its achievements are real. Indeed, Marvel enthusiasts may wonder if Botswana is linked to the Black Panther’s mythical kingdom of Wakanda.

In 2017, when former president Ketumile (Quett) Masire died, New York Times obituary writer Amisha Padnani described how he “for nearly two decades helped transform his arid and destitute country into the envy of other African nations.” In “The Fate of Africa,” author Martin Meredith applauded Botswana’s “enduring multiparty democracy” and “sound economic management,” noting that the government “has used its diamond riches for national advancement and maintained an administration free from corruption.”

And yet, more must be said before we end this African fairy tale. Consider these qualifying factors (oboy, here cometh the lecture):

- The discovery of diamonds soon after independence considerably eased Botswana’s economic difficulties — though responsible stewardship of this new wealth by Botswana’s leaders has been a key to prosperity.

- Other than benefiting from this good fortune, Botswana, like the Bechuanaland Protectorate before it, has depended economically and otherwise on its giant neighbor, the Republic of South Africa. To give a philatelic example of this dependency: In 1961, when South Africa introduced decimal currency, then-Bechuanaland Protectorate had to scramble to surcharge its sterling-currency stamps with decimals, then print its own. Botswana played a nuanced role before South Africa emerged as a multi-ethnic democracy in 1994. In the 1970s and ‘80s, Botswana yielded to South African pressures, but also harbored anti-apartheid fighters from the banned African National Congress.

- Not to be too cynical, but Bechuanaland is a backwater — nearly as large as Texas, most of it arid plains, with a population of 2.1 million (the Bronx?).

- Most telling in my view is that 79 percent of Motswana come from the same tribe — the Tswana ethnic group. The overlap between voter, tribe and government is commanding. I don’t want these factors to undermine my respect and admiration for Seretse Khama, Quett Masire and the other honest leaders and civil servants. In that respect, Botswana is a model state. It should be a model for neighboring Zimbabwe (population: 15.6 million), where the Shona tribe has a similarly lopsided majority, and corruption and political violence are epidemic. If tribal compatibility can foster good civil government, it clearly is not sufficient. And what about Kenya, where five major tribes vie for influence? Or the vast Congo, with hundreds of rival groups? Must an African state be ruled by one tribe to succeed? I hope not. I believe the most successful states are like my own, the USA. Our civic foundation is respect for individuals and their rights, regardless of tribe. I believe a diverse society is more dynamic and vital than a mono-cultural one. A diverse society does not countenance a member of one tribe killing another, and outlaws discrimination. This practice contradicts a social system in Kenya that pits Kikuyu against Luo, even as it has little use for a civic culture like Botswana’s, where one tribe runs everything. To rearrange Africa’s national boundaries so that they incorporate, as best as anyone can calculate, the sphere of one tribe’s influence — eek, what a chore! Is it even possible? What next? Alert members of each tribe that henceforth, “their” nation will be over there. So they’d better move if they don’t live there already. And if they don’t move? Will their fate be like that of the Hutu and Tutsi in Rwanda and Burundi? What about folks who intermarry? What about their children, and grandchildren? In the multiparty, multiethnic, tolerant model, all struggle together to find a way forward, making what contributions they can to a better life. (Here endeth the lecture.)

“legal” issue? How can the average collector distinguish one from the other in this philatelic hall of mirrors?

“legal” issue? How can the average collector distinguish one from the other in this philatelic hall of mirrors? Perhaps the editor need not have worried. Natural market correction serves the interests of philately. By 2009, it seems, most countries were well below 200 in new stamp issues for the year. They may have discovered the diminishing returns of

Perhaps the editor need not have worried. Natural market correction serves the interests of philately. By 2009, it seems, most countries were well below 200 in new stamp issues for the year. They may have discovered the diminishing returns of This, in a country with “poor economic performance,” “a fragile security situation,” “lack of infrastructure,” and so on. Indeed, what was Liberia thinking?

This, in a country with “poor economic performance,” “a fragile security situation,” “lack of infrastructure,” and so on. Indeed, what was Liberia thinking? issuing countries!”

issuing countries!”

Contemplate, dear reader, this image of a (cancelled-to-order) stamp, nominally from Equatorial Guinea, a tiny sovereign state on the west coast of Africa that has been grievously plundered and misruled by its leaders, both under Portuguese dominion and in the half-century since independence. The stamp is pretty enough — though the full-color reproduction of an Auguste Renoir painting of a very naked, very pink, big-bosomed young woman seems a bit, well, over the top. Can you seriously imagine a beleaguered citizen of this outlaw African state finding one of these in her or his local post office, for use on outgoing mail? Not likely. Remember all those rules set by the Universal Postal Union about what constitutes a legitimate stamp? (See blog post, September 2017.) Well, this stamp breaks most of those rules. It certainly has nothing to do with Equatorial Guinea. It’s doubtful it ever went on sale in the country, or if so was widely available for purchase. It is by no possible rhetorical stretch an emblem of Equatorial Guinean culture or sovereignty.

Contemplate, dear reader, this image of a (cancelled-to-order) stamp, nominally from Equatorial Guinea, a tiny sovereign state on the west coast of Africa that has been grievously plundered and misruled by its leaders, both under Portuguese dominion and in the half-century since independence. The stamp is pretty enough — though the full-color reproduction of an Auguste Renoir painting of a very naked, very pink, big-bosomed young woman seems a bit, well, over the top. Can you seriously imagine a beleaguered citizen of this outlaw African state finding one of these in her or his local post office, for use on outgoing mail? Not likely. Remember all those rules set by the Universal Postal Union about what constitutes a legitimate stamp? (See blog post, September 2017.) Well, this stamp breaks most of those rules. It certainly has nothing to do with Equatorial Guinea. It’s doubtful it ever went on sale in the country, or if so was widely available for purchase. It is by no possible rhetorical stretch an emblem of Equatorial Guinean culture or sovereignty. Ditto with the second stamp portrayed here — an image of Jiminy Cricket, the animated character from the Disney film “Pinocchio,” painting an Easter egg. Huh? Tell me why this is anything but a crass effort on the part of “Grenada Grenadines” (or better put, the philatelic agents) to cash in on the market for topical stamps. I wonder if there is an envelope bearing this stamp that actually went through the mail …

Ditto with the second stamp portrayed here — an image of Jiminy Cricket, the animated character from the Disney film “Pinocchio,” painting an Easter egg. Huh? Tell me why this is anything but a crass effort on the part of “Grenada Grenadines” (or better put, the philatelic agents) to cash in on the market for topical stamps. I wonder if there is an envelope bearing this stamp that actually went through the mail … ** The spurious issue from Bangladesh listed in the catalogue came from 1974. It was a suspiciously anodyne souvenir sheet and set of four stamps honoring the Universal

** The spurious issue from Bangladesh listed in the catalogue came from 1974. It was a suspiciously anodyne souvenir sheet and set of four stamps honoring the Universal Also interesting is one of the first sets issued after East Pakistan broke away from West Pakistan in 1971 and became Bangladesh. The set of 15 variously depicts a flag, a map and a portrait of Bangladesh’s first president, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. The catalogue bluntly notes that the set “was rejected by Bangladesh officials and not issued. Bangladesh representatives in England released these stamps, which were not valid, on

Also interesting is one of the first sets issued after East Pakistan broke away from West Pakistan in 1971 and became Bangladesh. The set of 15 variously depicts a flag, a map and a portrait of Bangladesh’s first president, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. The catalogue bluntly notes that the set “was rejected by Bangladesh officials and not issued. Bangladesh representatives in England released these stamps, which were not valid, on  Feb. 1, 1972.” The same designs appear in the first official set from Bangladesh (examples at right) — though the nation’s name is spelled in two words — Bangla and Desh. I have not learned why the other set was rejected, and illegal. I admit I have it in my collection, though. I bought it for a couple of bucks at a stamp show. I wonder if the violent and bloody birth pangs of Bangladesh had something to do with this mixup. Peace had barely been restored and the Sheikh was released from solitary confinement only in January, a month before the spurious stamps were issued. Things never really settled down under Sheikh Mujib — earnest, bespectacled, charismatic and a dogmatic socialist. In 1975, he and members of his family were gunned down by army officers during a coup that returned the region to benighted martial law and years of unrest.

Feb. 1, 1972.” The same designs appear in the first official set from Bangladesh (examples at right) — though the nation’s name is spelled in two words — Bangla and Desh. I have not learned why the other set was rejected, and illegal. I admit I have it in my collection, though. I bought it for a couple of bucks at a stamp show. I wonder if the violent and bloody birth pangs of Bangladesh had something to do with this mixup. Peace had barely been restored and the Sheikh was released from solitary confinement only in January, a month before the spurious stamps were issued. Things never really settled down under Sheikh Mujib — earnest, bespectacled, charismatic and a dogmatic socialist. In 1975, he and members of his family were gunned down by army officers during a coup that returned the region to benighted martial law and years of unrest. While we’re on the subject of Bangladesh, how about these provisional overprints of Pakistani

While we’re on the subject of Bangladesh, how about these provisional overprints of Pakistani

those sets honoring Winston Churchill and JFK, the Olympics, famous artists, butterflies and the rest. My Scott catalogue wouldn’t even show pictures of these “non-standard” non-stamps.

those sets honoring Winston Churchill and JFK, the Olympics, famous artists, butterflies and the rest. My Scott catalogue wouldn’t even show pictures of these “non-standard” non-stamps.

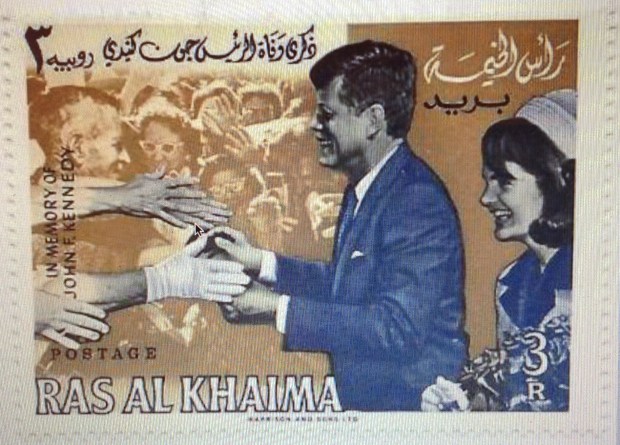

No need to play this up, but is that really a succession of Catholic-approved Pietas in these art stamps from Umm al Quiwain (below) ? It’s downright ecumenical of this Muslim sheikdom to honor Christian icons on its stamps. What next — a celebration of Jewish holidays? At right is the obligatory butterfly stamp, this one from Ras al Khaima, more or less announcing that this stamp, like the others, is pretty much illegal.

No need to play this up, but is that really a succession of Catholic-approved Pietas in these art stamps from Umm al Quiwain (below) ? It’s downright ecumenical of this Muslim sheikdom to honor Christian icons on its stamps. What next — a celebration of Jewish holidays? At right is the obligatory butterfly stamp, this one from Ras al Khaima, more or less announcing that this stamp, like the others, is pretty much illegal.

Island, Diamond Island, Large Island,

Island, Diamond Island, Large Island,

locomotive, a Cadillac … what in the world does any of this have to do with Bequia? As for the pretty butterfly stamps (see below), well, don’t they speak for themselves by now?

locomotive, a Cadillac … what in the world does any of this have to do with Bequia? As for the pretty butterfly stamps (see below), well, don’t they speak for themselves by now?

There was a time when Cambodia issued some of the world’s most beautiful stamps — delicate works of art that combined expert engraving, rich and subtle coloring, and arresting subjects. Here are some I captured in images from the Internet:

There was a time when Cambodia issued some of the world’s most beautiful stamps — delicate works of art that combined expert engraving, rich and subtle coloring, and arresting subjects. Here are some I captured in images from the Internet:

penny varieties — perhaps at an inflated price from the Kenmore Stamp Company approval service, I decided in my 12-year-old, penny-pinching brain that I would try to save myself the cost of these stamps, which would be duplicates. And so I continued:)

penny varieties — perhaps at an inflated price from the Kenmore Stamp Company approval service, I decided in my 12-year-old, penny-pinching brain that I would try to save myself the cost of these stamps, which would be duplicates. And so I continued:) On April 29, I received a puzzling response from British Guiana, dated April 19. As it happens, I saved the rather undistinguished envelope in my Worldwide Covers album (see right), with the note inside. It was a form letter with some blanks filled in, titled, “British Guiana Postage and Revenue Stamps.” It came from the Chief Accountant at the General Post Office, Georgetown, Demerara State, British Guiana:

On April 29, I received a puzzling response from British Guiana, dated April 19. As it happens, I saved the rather undistinguished envelope in my Worldwide Covers album (see right), with the note inside. It was a form letter with some blanks filled in, titled, “British Guiana Postage and Revenue Stamps.” It came from the Chief Accountant at the General Post Office, Georgetown, Demerara State, British Guiana: South American colony was a way-station for mail steaming from Europe to the Caribbean colonies. Let’s see what a map of that route would look like …

South American colony was a way-station for mail steaming from Europe to the Caribbean colonies. Let’s see what a map of that route would look like … Philoweg 9

Philoweg 9 amounted to nine shillings eleven pence in their currency. Apparently the money order has gone to the Cayman Islands and the letter to you. Could you please forward the letter to the Cayman Islands, so that the order may be filled. I am enclosing your mail order form, with postal money order for XXXX German marks. According to German postal authorities, the money order must be sent under separate cover. I hope that the error may be straightened out, and that I may soon receive stamps from both Georgetowns. Yours very truly (Fred: I’ll take them up to $1. You figure what you’d like, and we’ll add them together)

amounted to nine shillings eleven pence in their currency. Apparently the money order has gone to the Cayman Islands and the letter to you. Could you please forward the letter to the Cayman Islands, so that the order may be filled. I am enclosing your mail order form, with postal money order for XXXX German marks. According to German postal authorities, the money order must be sent under separate cover. I hope that the error may be straightened out, and that I may soon receive stamps from both Georgetowns. Yours very truly (Fred: I’ll take them up to $1. You figure what you’d like, and we’ll add them together)

(To) Mr. Fred Fiske

(To) Mr. Fred Fiske

provisionals. Today only one example survives of the one-cent, printed on dark magenta paper, bearing the colony’s badge of a sailing ship in black ink. When this rarest of stamps changes hands, which is infrequently, it goes for millions.

provisionals. Today only one example survives of the one-cent, printed on dark magenta paper, bearing the colony’s badge of a sailing ship in black ink. When this rarest of stamps changes hands, which is infrequently, it goes for millions.

black wax seals, embossed with a crown and what looks like the letters “STAMP AND PO’S.” The envelope inside contained gorgeous stamps, post-office fresh,

black wax seals, embossed with a crown and what looks like the letters “STAMP AND PO’S.” The envelope inside contained gorgeous stamps, post-office fresh,  from one cent all the way to the $5. I gave Pa the complete set and kept the second set to the $1, which was as far as my money went.

from one cent all the way to the $5. I gave Pa the complete set and kept the second set to the $1, which was as far as my money went.

On Oct. 26, a packet arrived from the Cayman Islands. In my Worldwide Covers album I still have the envelope, postmarked Oct. 23. That’s more than six months after I sent that first letter April 10, supposedly steaming toward the Caymans, but ending up instead in … British Guiana.

On Oct. 26, a packet arrived from the Cayman Islands. In my Worldwide Covers album I still have the envelope, postmarked Oct. 23. That’s more than six months after I sent that first letter April 10, supposedly steaming toward the Caymans, but ending up instead in … British Guiana. My cover album page also preserves a notification card from the Heidelberg post office that might help explain the delay in the Cayman Islands delivery. To be precise, however, I would have to decipher such phrases as “Nachforschungen nach dem Verblieb,” and “Nachforschungendegebuehr wurden by der Aushaendigung diesen Schreibens erhoben.” The gist of it, as far as I can make out, is that the Heidelberg P.O., in response to

My cover album page also preserves a notification card from the Heidelberg post office that might help explain the delay in the Cayman Islands delivery. To be precise, however, I would have to decipher such phrases as “Nachforschungen nach dem Verblieb,” and “Nachforschungendegebuehr wurden by der Aushaendigung diesen Schreibens erhoben.” The gist of it, as far as I can make out, is that the Heidelberg P.O., in response to

where it arrived after just three days. By the way, the card with the explanation from the Heidelberg P.O. was sent to me March 30, 1962 — more than five months after I got my stamps, and nearly a year since I sent out my first letter on April 10, 1961.

where it arrived after just three days. By the way, the card with the explanation from the Heidelberg P.O. was sent to me March 30, 1962 — more than five months after I got my stamps, and nearly a year since I sent out my first letter on April 10, 1961. I must add this piquant detail: the itemized list included in the packet (see right) shows that the postmaster (“… your obedient servant, etc.”) had thoughtfully omitted the 1/4d or 1/2d stamps, thus fulfilling my ridiculous request in the original letter of April 8, and saving me three-quarters of a penny for the unnecessary duplicates …

I must add this piquant detail: the itemized list included in the packet (see right) shows that the postmaster (“… your obedient servant, etc.”) had thoughtfully omitted the 1/4d or 1/2d stamps, thus fulfilling my ridiculous request in the original letter of April 8, and saving me three-quarters of a penny for the unnecessary duplicates … another, thick envelope from British Guiana, also preserved in my Worldwide Covers album (see right). This one arrived April 3, 1962.

another, thick envelope from British Guiana, also preserved in my Worldwide Covers album (see right). This one arrived April 3, 1962. The envelope and letter from Ascension, preserved in my Worldwide Covers album (see right) and dated Dec. 4, 1961, reads: “Dear Sir, Thank you for your letter of the 15th October.

The envelope and letter from Ascension, preserved in my Worldwide Covers album (see right) and dated Dec. 4, 1961, reads: “Dear Sir, Thank you for your letter of the 15th October. ** My envelope mailed Jan. 4, 1962 to “Postmisstress (sic), General Post Office, Georgetown, Ascension.” On the back is a circular postmark inscribed, “Jan. 7, 1962 — G.P.O., British Guiana.”

** My envelope mailed Jan. 4, 1962 to “Postmisstress (sic), General Post Office, Georgetown, Ascension.” On the back is a circular postmark inscribed, “Jan. 7, 1962 — G.P.O., British Guiana.” ** An envelope “On Her Majesty’s Service,” inscribed, “Jan. 12, 1962, G.P.O. Georgetown, British Guiana,” addressed to “The Postmaster General, General Post Office, Georgetown, Ascension.” This envelope presumably included the envelope I had intended to send to Georgetown, Ascension, but which ended up in Georgetown, British Guiana — just like my earlier letter to George Town, Cayman Islands. On the back of this second envelope was another circular date stamp, inscribed “22 Ene (Jan.) Aeropostal – Paraguay,” indicating that my letter had been misdelivered once again, this time thousands of miles south of British Guiana — to Paraguay!

** An envelope “On Her Majesty’s Service,” inscribed, “Jan. 12, 1962, G.P.O. Georgetown, British Guiana,” addressed to “The Postmaster General, General Post Office, Georgetown, Ascension.” This envelope presumably included the envelope I had intended to send to Georgetown, Ascension, but which ended up in Georgetown, British Guiana — just like my earlier letter to George Town, Cayman Islands. On the back of this second envelope was another circular date stamp, inscribed “22 Ene (Jan.) Aeropostal – Paraguay,” indicating that my letter had been misdelivered once again, this time thousands of miles south of British Guiana — to Paraguay! ** The third envelope was a larger size, white and flimsy, certainly large enough to contain both my original letter to Ascension and the follow-up envelope from British Guiana. It carried a circular date stamp, inscribed, “Aeropostal, Paraguay, 10 Feb. 1962.” This envelope, like the second one, was addressed to “Postmaster General, General Post Office, Georgetown, Ascension.” Interestingly, “Georgetown” was crossed out — apparently some official decided there were just too many Georgetowns involved! A registration sticker identified the sender’s location as “Asuncion, Republica del

** The third envelope was a larger size, white and flimsy, certainly large enough to contain both my original letter to Ascension and the follow-up envelope from British Guiana. It carried a circular date stamp, inscribed, “Aeropostal, Paraguay, 10 Feb. 1962.” This envelope, like the second one, was addressed to “Postmaster General, General Post Office, Georgetown, Ascension.” Interestingly, “Georgetown” was crossed out — apparently some official decided there were just too many Georgetowns involved! A registration sticker identified the sender’s location as “Asuncion, Republica del  Paraguay.” And here comes a real shocker: A rubber stamp in the lower right corner declared: “Missent to British Guiana.” (see enlargement, right; apparently this happened often enough that it warranted a rubber stamp!) Sure enough, on the back of the envelope from Paraguay was another circular date stamp confirming arrival in British Guiana, inscribed, “Registered Airmail, 21 Feb. 1962.”

Paraguay.” And here comes a real shocker: A rubber stamp in the lower right corner declared: “Missent to British Guiana.” (see enlargement, right; apparently this happened often enough that it warranted a rubber stamp!) Sure enough, on the back of the envelope from Paraguay was another circular date stamp confirming arrival in British Guiana, inscribed, “Registered Airmail, 21 Feb. 1962.”

The envelope postmarked “Mostar 10.2.93” arrived in my mailbox, in response to my international postal coupon, without a legal postage stamp, an illegal stamp or even a Cinderella. Instead, it carried an ink stamp that read: “Postarina Placena / Port Paye” — postage paid.

The envelope postmarked “Mostar 10.2.93” arrived in my mailbox, in response to my international postal coupon, without a legal postage stamp, an illegal stamp or even a Cinderella. Instead, it carried an ink stamp that read: “Postarina Placena / Port Paye” — postage paid. signed “Trajaneski Dragi,” that was as poignant as it was informative. “Dear Fred Fiske,” the note read. “We haven’t eny stamps. If we have it be late. I am sorry.”

signed “Trajaneski Dragi,” that was as poignant as it was informative. “Dear Fred Fiske,” the note read. “We haven’t eny stamps. If we have it be late. I am sorry.” Mostar lies in the southwest of the

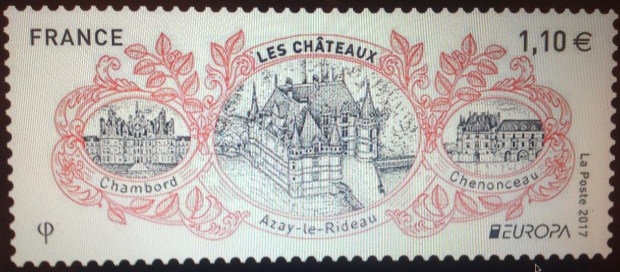

Mostar lies in the southwest of the The Serbian postal authority — or rather, its private contractor — launched a campaign to have its Europa 2017 stamp (right) chosen as the most beautiful in Europe. In 2017, the multi-nation Europa issue settled on a theme of castles that are still standing. In its pitch, the Serb promoters sounded a theme of peaceful coexistence you don’t hear often enough these days. “Once seen as symbols of power, defence, war and supremacy over other kingdoms, it is extremely positive to see these monuments survive the sociological and political evolutions to have a much more peaceful and beautiful connotation at present times.” The uplift continued: “Today these castles are preserved as monuments that do not only teach us about our own past history, but they can also demonstrate how we no longer need fortified walls in Europe, in order to live in safety.” Then came the hook: “Poste Srpske through this topic are proud to present the fortress Kastel, and we urge you to vote for it via an online competition organized by the Post Europ, the association that represents European public postal operators …” (The deadline for votes was Sept. 9; 2017; for the contest results, go to

The Serbian postal authority — or rather, its private contractor — launched a campaign to have its Europa 2017 stamp (right) chosen as the most beautiful in Europe. In 2017, the multi-nation Europa issue settled on a theme of castles that are still standing. In its pitch, the Serb promoters sounded a theme of peaceful coexistence you don’t hear often enough these days. “Once seen as symbols of power, defence, war and supremacy over other kingdoms, it is extremely positive to see these monuments survive the sociological and political evolutions to have a much more peaceful and beautiful connotation at present times.” The uplift continued: “Today these castles are preserved as monuments that do not only teach us about our own past history, but they can also demonstrate how we no longer need fortified walls in Europe, in order to live in safety.” Then came the hook: “Poste Srpske through this topic are proud to present the fortress Kastel, and we urge you to vote for it via an online competition organized by the Post Europ, the association that represents European public postal operators …” (The deadline for votes was Sept. 9; 2017; for the contest results, go to  In the interests of intra-national good will and fair play, it behooves me to point out that the other two stamp-producing entities in Bosnia-Herzegovina also put out Europa 1017 castle stamps. I don’t know whether they were entered in the contest for Europe’s most-beautiful stamp, but they are pretty nice, don’t you think? Which one of the three do you prefer?

In the interests of intra-national good will and fair play, it behooves me to point out that the other two stamp-producing entities in Bosnia-Herzegovina also put out Europa 1017 castle stamps. I don’t know whether they were entered in the contest for Europe’s most-beautiful stamp, but they are pretty nice, don’t you think? Which one of the three do you prefer?

Because of my

Because of my Also considered spurious is another set (right), which is listed by a dealer as “Bosnia-Herze-govina/Croatian overprints,” and consists of eight stamps from the Yugoslav definitives, this time with “Jugoslavija” blacked out and replaced by the checkerboard Croatian coat-of-arms.

Also considered spurious is another set (right), which is listed by a dealer as “Bosnia-Herze-govina/Croatian overprints,” and consists of eight stamps from the Yugoslav definitives, this time with “Jugoslavija” blacked out and replaced by the checkerboard Croatian coat-of-arms. Another set,

Another set,

Bosnia-Herzegovina has had stamps since the 1870s, when it was part of Austro-Hungary. These stamps depicting a charming Bosniak girl were issued in 1918, at the very end of the empire. They are not “real” stamps, but rather newspaper revenue labels. You’ll notice there isn’t even a country name on them. After Bosnia-Herzegovina became part of Yugoslavia, the “anonymous” stamps were reissued, also surcharged (example above), and used for postage. Thus we have an example of a Cinderella stamp

Bosnia-Herzegovina has had stamps since the 1870s, when it was part of Austro-Hungary. These stamps depicting a charming Bosniak girl were issued in 1918, at the very end of the empire. They are not “real” stamps, but rather newspaper revenue labels. You’ll notice there isn’t even a country name on them. After Bosnia-Herzegovina became part of Yugoslavia, the “anonymous” stamps were reissued, also surcharged (example above), and used for postage. Thus we have an example of a Cinderella stamp  that was repurposed as a legitimate postage stamp.

that was repurposed as a legitimate postage stamp.

Here are more examples of Yugoslav definitives overprinted for “local” use by the territories of

Here are more examples of Yugoslav definitives overprinted for “local” use by the territories of  Istra (above right), Sandza (right) and Zapadna (below right). I could spend time trying to

Istra (above right), Sandza (right) and Zapadna (below right). I could spend time trying to  figure out if these are cities, or regions, or states of mind in the Balkan universe — but I won’t. I am intrigued by the longhorn in the Istra coat of arms, the Islamic star and crescent moon for Sandzak, and the fleur de lis and banner for Zapadna — they all suggest multi-ethnic aspirations in contention. I appreciate the struggle, and am glad that everyone seems to have worked things out sufficiently to be living in peace. I like to think of these stamps — all illegal, as far as I know — as emblems of a process that has led to tolerance, coexistence and self-expression.

figure out if these are cities, or regions, or states of mind in the Balkan universe — but I won’t. I am intrigued by the longhorn in the Istra coat of arms, the Islamic star and crescent moon for Sandzak, and the fleur de lis and banner for Zapadna — they all suggest multi-ethnic aspirations in contention. I appreciate the struggle, and am glad that everyone seems to have worked things out sufficiently to be living in peace. I like to think of these stamps — all illegal, as far as I know — as emblems of a process that has led to tolerance, coexistence and self-expression. The breakaway Balkan province of Kosovo is a whole story of its own, which I won’t try to retell here. Instead, I display two philatelic artifacts from its modern history. The first set, above, is a Cinderella issue representing Kosovo’s national aspirations.

The breakaway Balkan province of Kosovo is a whole story of its own, which I won’t try to retell here. Instead, I display two philatelic artifacts from its modern history. The first set, above, is a Cinderella issue representing Kosovo’s national aspirations.  The stamps at right were issued on behalf of the NATO peacekeeping force that did so much to keep things from going from bad to worse in Kosovo. Emerging from U.N. supervision, Kosovo declared its independence in 2008. Its autonomy remains in dispute — Kosovo is not a member of the U.N. or the Universal Postal Union, so its stamps may or may not be legal …

The stamps at right were issued on behalf of the NATO peacekeeping force that did so much to keep things from going from bad to worse in Kosovo. Emerging from U.N. supervision, Kosovo declared its independence in 2008. Its autonomy remains in dispute — Kosovo is not a member of the U.N. or the Universal Postal Union, so its stamps may or may not be legal … Here are early stamps from the Serbian side in Bosnia-Herzigovina. In the top row, the stamps are inscribed “Republica Srpskpa,” which corresponds to the name for territory within national borders, but somehow distinct from the federation itself (see map, above). The lower row of stamps add the word Krajina. This refers to Serbia’s claim to territory extending into Croatia, essentially redefining the borders (krajina means “frontier.”) NIce try, Serbia. Eventually the krajina was reaffirmed as the pre-existing border between Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. The Krajina label was never recognized internationally, so these stamps are illegals, or Cinderellas — though as you see below, there are postally used examples of these stamps on covers.

Here are early stamps from the Serbian side in Bosnia-Herzigovina. In the top row, the stamps are inscribed “Republica Srpskpa,” which corresponds to the name for territory within national borders, but somehow distinct from the federation itself (see map, above). The lower row of stamps add the word Krajina. This refers to Serbia’s claim to territory extending into Croatia, essentially redefining the borders (krajina means “frontier.”) NIce try, Serbia. Eventually the krajina was reaffirmed as the pre-existing border between Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. The Krajina label was never recognized internationally, so these stamps are illegals, or Cinderellas — though as you see below, there are postally used examples of these stamps on covers. Here are a couple of covers I purchased on eBay for a few bucks each. The one on the left features stamps from Republica Srpska which are supposed to be illegal, but were postally accepted just the same on this letter to Italy. The stamps

Here are a couple of covers I purchased on eBay for a few bucks each. The one on the left features stamps from Republica Srpska which are supposed to be illegal, but were postally accepted just the same on this letter to Italy. The stamps  on the the right-hand cover were used internally. As the postmarks indicate, the covers originated in Banja Luka, a city in northern Bosnia-Herzegovina that today lies within the boundaries of the Serbian-claimed territory.

on the the right-hand cover were used internally. As the postmarks indicate, the covers originated in Banja Luka, a city in northern Bosnia-Herzegovina that today lies within the boundaries of the Serbian-claimed territory. This oddment at right was listed on eBay as “Travnik probe 1992.” I believe it was issued during the Croat-Muslim conflict around Travnik in the central region of Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1992. (The fleu-de-lis design echoes the Zapadna Cinderellas, above.) The price on eBay is just a few bucks, but I’d pay more than that for an example of this stamp postally used on an envelope.

This oddment at right was listed on eBay as “Travnik probe 1992.” I believe it was issued during the Croat-Muslim conflict around Travnik in the central region of Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1992. (The fleu-de-lis design echoes the Zapadna Cinderellas, above.) The price on eBay is just a few bucks, but I’d pay more than that for an example of this stamp postally used on an envelope. I include these two covers I bought for my collection, both mailed in Mostar, to illustrate how illegal stamps can be used on legitimately posted letters. Both letters were mailed internally — the one below right didn’t even leave Mostar. Something about the postmarks struck me. The envelope above left is dated 30.2.92 — Feb. 30,

I include these two covers I bought for my collection, both mailed in Mostar, to illustrate how illegal stamps can be used on legitimately posted letters. Both letters were mailed internally — the one below right didn’t even leave Mostar. Something about the postmarks struck me. The envelope above left is dated 30.2.92 — Feb. 30,  1992. The one below it was postmarked 02.08.92 — Aug. 2, 1992. You may recall that I mailed my international postal coupon to Mostar in June, 1992 — four months after the first cover was postmarked, two months before the second cover was processed. My letter should have arrived in Mostar in plenty of time for a return cover to be embellished with those same stamps, legal or not. OK, I understand postal officials may have been distracted by a few things, including civil war. What may be most surprising is that old Trajaneski Dragi got around to responding to my inquiry at all. By February 1993, it seems there were no more stamps available — legal or illegal. Where did the stamps go? Did they just run out? Were they confiscated by one side or the other?

1992. The one below it was postmarked 02.08.92 — Aug. 2, 1992. You may recall that I mailed my international postal coupon to Mostar in June, 1992 — four months after the first cover was postmarked, two months before the second cover was processed. My letter should have arrived in Mostar in plenty of time for a return cover to be embellished with those same stamps, legal or not. OK, I understand postal officials may have been distracted by a few things, including civil war. What may be most surprising is that old Trajaneski Dragi got around to responding to my inquiry at all. By February 1993, it seems there were no more stamps available — legal or illegal. Where did the stamps go? Did they just run out? Were they confiscated by one side or the other? Finally, here is an image I captured from the internet. The overprint is intriguing: It sets a date — 11.05.1994 — that’s May 11, 1994, more than a year before the Dayton Accords would end the Balkan conflict. The stamps bear the inscription “BiH Konfederacija” — Confederation of Bosnia- Herzegovina — and alternating cities, Vienna and Geneva. What role did these cities full of diplomats and international civil servants play, along the road to Dayton? And what about that word, confederacija? The Dayton agreement established Bosnia-Herzegovina as a formal “federation,” not a loose “confederation” of sovereign states. Thus, these stamps not only are Cinderellas, but they rapidly were superseded by history.

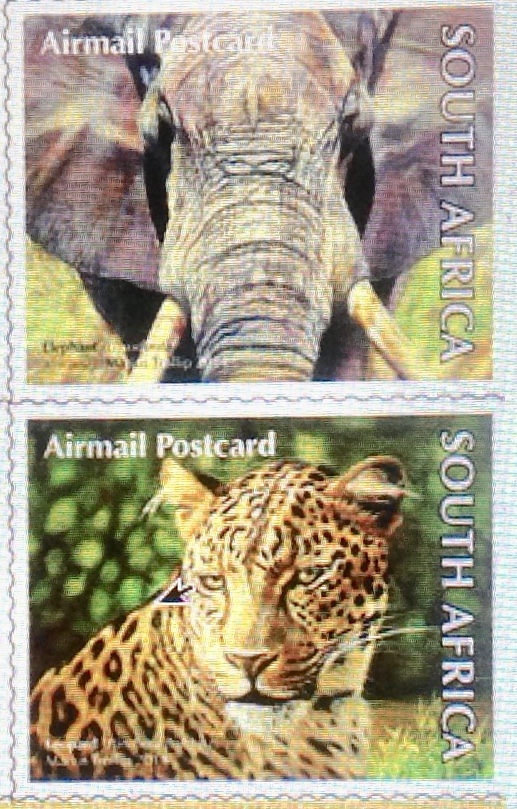

Finally, here is an image I captured from the internet. The overprint is intriguing: It sets a date — 11.05.1994 — that’s May 11, 1994, more than a year before the Dayton Accords would end the Balkan conflict. The stamps bear the inscription “BiH Konfederacija” — Confederation of Bosnia- Herzegovina — and alternating cities, Vienna and Geneva. What role did these cities full of diplomats and international civil servants play, along the road to Dayton? And what about that word, confederacija? The Dayton agreement established Bosnia-Herzegovina as a formal “federation,” not a loose “confederation” of sovereign states. Thus, these stamps not only are Cinderellas, but they rapidly were superseded by history. ** A South Africa set from the late apartheid era. It is not very valuable. though it is a very pretty set of birds, plants and fish — a desirable item for topical collectors, I would think. On second thought, though, it poses a challenge to topical cllectors, in that it combines three specialties — birds on stamps, plants on stamps, fish on stamps. Then again, topical collectors may not care about complete sets. I’ll have to find out some day …

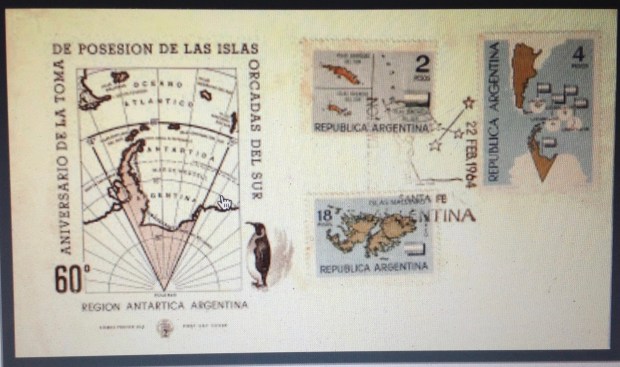

** A South Africa set from the late apartheid era. It is not very valuable. though it is a very pretty set of birds, plants and fish — a desirable item for topical collectors, I would think. On second thought, though, it poses a challenge to topical cllectors, in that it combines three specialties — birds on stamps, plants on stamps, fish on stamps. Then again, topical collectors may not care about complete sets. I’ll have to find out some day … ** A long, incomplete set from the 1980s Falkland Island Dependencies. The stamps were cheap, probably worth little if anything — but oh! What scenes of desolation: “Shag rocks” … “Bird and Willis Islands” … “Twitchern Rock and Cook Island” … These stamps purportedly were printed for use on the forlorn islands of Sandwich and the South Shetlands, closer to Antarctica than the southeast coast of Argentina. Interestingly, it was also in the 1980s that Argentina went to war with Great Britain over these islands, along with the relatively nearby Falkland Islands. The British prevailed, and in this set reaffirm their claim to the Falkland Island Dependencies. Argentina, the loser, has never given up its claims. (For more about this, see my post on Stamp Wars, October 2017.)

** A long, incomplete set from the 1980s Falkland Island Dependencies. The stamps were cheap, probably worth little if anything — but oh! What scenes of desolation: “Shag rocks” … “Bird and Willis Islands” … “Twitchern Rock and Cook Island” … These stamps purportedly were printed for use on the forlorn islands of Sandwich and the South Shetlands, closer to Antarctica than the southeast coast of Argentina. Interestingly, it was also in the 1980s that Argentina went to war with Great Britain over these islands, along with the relatively nearby Falkland Islands. The British prevailed, and in this set reaffirm their claim to the Falkland Island Dependencies. Argentina, the loser, has never given up its claims. (For more about this, see my post on Stamp Wars, October 2017.) ** A souvenir sheet from Togo, 1961, This fills a large space on a page of my Togo collection, which is far from complete. Indeed, I have no great ambitions for my Togo collection. Still, Togo’s role in colonial and post-colonial Africa grabs my interest. The slogan on this set of stamps — Commission Economiques des Nations Unies Pour L’Afrique (Economic Commission of Nations United for Africa) — sounds poignantly hopeful and naive, even deluded, given what has happened in Togo and west Africa, and Africa generally, over the last 50 years.

** A souvenir sheet from Togo, 1961, This fills a large space on a page of my Togo collection, which is far from complete. Indeed, I have no great ambitions for my Togo collection. Still, Togo’s role in colonial and post-colonial Africa grabs my interest. The slogan on this set of stamps — Commission Economiques des Nations Unies Pour L’Afrique (Economic Commission of Nations United for Africa) — sounds poignantly hopeful and naive, even deluded, given what has happened in Togo and west Africa, and Africa generally, over the last 50 years. ** The 250 franc from Upper Volta (1968) cost a couple of bucks. In a beautifully engraved, multi-color cameo, it depicts a satellite in space, over the West African capital city’s relay station. The inscription reads, “Ouagadougou — Station Spatiale.” There is a spot in my Africa albums for this stamp, though I harbor no ambitions ever to assemble a valuable collection from Upper Vola (now Burkina Faso) or most other countries. What draws me is the history of post-colonial Africa. I cling to the fond hopes portrayed in these stamps of international cooperation, progress, peace and human development. What breaks my heart is that these hopes soared more than 50 years ago, then came crashing down in the ensuing decades.

** The 250 franc from Upper Volta (1968) cost a couple of bucks. In a beautifully engraved, multi-color cameo, it depicts a satellite in space, over the West African capital city’s relay station. The inscription reads, “Ouagadougou — Station Spatiale.” There is a spot in my Africa albums for this stamp, though I harbor no ambitions ever to assemble a valuable collection from Upper Vola (now Burkina Faso) or most other countries. What draws me is the history of post-colonial Africa. I cling to the fond hopes portrayed in these stamps of international cooperation, progress, peace and human development. What breaks my heart is that these hopes soared more than 50 years ago, then came crashing down in the ensuing decades.

** The Guernsey set (1-7) may look pretty dull, but I was attracted by the color varieties and the sense of completeness about this historic set; or rather two sets, one with watermarks, one without. Notice that these sets, like GB stamps, do not carry the name of a country. In a way that seems somehow ineffably English, it seems Great Britain, having invented stamps, never had to stoop so low as to flaunt its name on its postage labels — or those of its channel islands (though Guerney, Jersey and the Isle of Man soon did put their names on their stamps.) Indeed, the islands in the English Channel developed philatelic cottage industries, with colorful and

** The Guernsey set (1-7) may look pretty dull, but I was attracted by the color varieties and the sense of completeness about this historic set; or rather two sets, one with watermarks, one without. Notice that these sets, like GB stamps, do not carry the name of a country. In a way that seems somehow ineffably English, it seems Great Britain, having invented stamps, never had to stoop so low as to flaunt its name on its postage labels — or those of its channel islands (though Guerney, Jersey and the Isle of Man soon did put their names on their stamps.) Indeed, the islands in the English Channel developed philatelic cottage industries, with colorful and  collectible stamps down through the years. Guernsey’s first philatelic presence came during World War II, when the Nazis occupied the island, along with neighboring Jersey — so close, yet so far from Winston Churchill’s citadel. These newer stamps, from the 1950s, featured the pretty young Queen Elizabeth II. They only cost a couple of bucks, yet they seem to herald the modern, post-war era.

collectible stamps down through the years. Guernsey’s first philatelic presence came during World War II, when the Nazis occupied the island, along with neighboring Jersey — so close, yet so far from Winston Churchill’s citadel. These newer stamps, from the 1950s, featured the pretty young Queen Elizabeth II. They only cost a couple of bucks, yet they seem to herald the modern, post-war era. What a dull-looking stamp!

What a dull-looking stamp!

so many years of the same design, now there was something new! One wonders: If the purpose of maintaining the design was in part to convey a sense of the British empire’s soliditiy, continuity, normalcy and orderliness, then what did the radical departure into gaudy labels in 1938 signify?

so many years of the same design, now there was something new! One wonders: If the purpose of maintaining the design was in part to convey a sense of the British empire’s soliditiy, continuity, normalcy and orderliness, then what did the radical departure into gaudy labels in 1938 signify?  This shift in the philatelic paradigm surely was a signal — unconscious, perhaps — that the colonial era was no longer going to be quite so predictable …

This shift in the philatelic paradigm surely was a signal — unconscious, perhaps — that the colonial era was no longer going to be quite so predictable … III. What a lot of stamps there are in this set! Between the 2-cent stamp and the 5-rupee value I count 24 varieties — considerably more than the average for the first George VI set in other colonies. (Though I must add that right from the beginning, Seychelles did issue more long sets with color varieties

III. What a lot of stamps there are in this set! Between the 2-cent stamp and the 5-rupee value I count 24 varieties — considerably more than the average for the first George VI set in other colonies. (Though I must add that right from the beginning, Seychelles did issue more long sets with color varieties  than most colonies; please don’t ask me why. Mauritius, an island colony a mere 1,000+ miles away in the Indian Ocean, also seemed to issue long sets — 20 stamps or more,

than most colonies; please don’t ask me why. Mauritius, an island colony a mere 1,000+ miles away in the Indian Ocean, also seemed to issue long sets — 20 stamps or more,  with different colors. Go figure.) Over the past 18 years I managed to accumulate a nearly complete Seychelles 1938 George VI set, which is tantalizing for a diehard collector/investor like me. But an affordable 1 rupee yellow-green eluded me — until now. Believe it or not, 37.99 euros is actually a great price for a decent copy of the stamp —

with different colors. Go figure.) Over the past 18 years I managed to accumulate a nearly complete Seychelles 1938 George VI set, which is tantalizing for a diehard collector/investor like me. But an affordable 1 rupee yellow-green eluded me — until now. Believe it or not, 37.99 euros is actually a great price for a decent copy of the stamp —  even a hinged one, like this. Other prices online ranged up past $50, much higher for a never-hinged example. To have the set complete is a special pleasure of stamp-collecting — particularly if it results from a process of patient accumulation over time.

even a hinged one, like this. Other prices online ranged up past $50, much higher for a never-hinged example. To have the set complete is a special pleasure of stamp-collecting — particularly if it results from a process of patient accumulation over time. V. The 1 rupee yellow-green could be considered the key value of the set. It is about 100 times more valuable than the 1 rupee gray that took its place in 1941. At least, I figure that’s what happened — all these earlier values were withdrawn, or at least no longer produced, after just three years. The relatively short circulation lifespan of those earlier stamps no doubt helped to account for their subsequent rarity and inflated value.

V. The 1 rupee yellow-green could be considered the key value of the set. It is about 100 times more valuable than the 1 rupee gray that took its place in 1941. At least, I figure that’s what happened — all these earlier values were withdrawn, or at least no longer produced, after just three years. The relatively short circulation lifespan of those earlier stamps no doubt helped to account for their subsequent rarity and inflated value. The remaining set stayed in circulation from 1941 on, until a new set appeared in March 1952, featuring a portrait of a shockingly aged George VI. (Unfortunately, the king had died a month

The remaining set stayed in circulation from 1941 on, until a new set appeared in March 1952, featuring a portrait of a shockingly aged George VI. (Unfortunately, the king had died a month  earlier; the resourceful stamp makers simply replaced the portrait of George VI with a cameo of the young Queen Elizabeth II and issued that set in 1954; notice how the stamp-makers kept the same gray-and-white coloring for the 1-rupee stamp right on through. More sets followed; the Seychelles gained independence in 1976.)

earlier; the resourceful stamp makers simply replaced the portrait of George VI with a cameo of the young Queen Elizabeth II and issued that set in 1954; notice how the stamp-makers kept the same gray-and-white coloring for the 1-rupee stamp right on through. More sets followed; the Seychelles gained independence in 1976.)

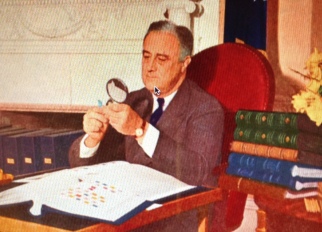

while he soared into the imaginative realms of his magnificent stamp collection, once said, “I owe my life to my hobbies — especially stamp collecting.”

while he soared into the imaginative realms of his magnificent stamp collection, once said, “I owe my life to my hobbies — especially stamp collecting.”

1. When this Bolivian postage stamp map (right) was first issued, in 1928, it caused an uproar in neighboring Paraguay. The two nations had been having a long dispute over the semi-arid, sparsely populated Chaco region. Paraguay and Bolivia, both land-locked, were among the poorest nations in South America. This postage stamp for the first time boldly named the territory that would extend Bolivia’s southeast border, “Chaco Boliviano.”

1. When this Bolivian postage stamp map (right) was first issued, in 1928, it caused an uproar in neighboring Paraguay. The two nations had been having a long dispute over the semi-arid, sparsely populated Chaco region. Paraguay and Bolivia, both land-locked, were among the poorest nations in South America. This postage stamp for the first time boldly named the territory that would extend Bolivia’s southeast border, “Chaco Boliviano.” A year earlier, Paraguay had established its philatelic claim to the Chaco, a region that constituted about 40 percent of its northern land mass. A Paraguayan stamp in 1927 (right) displayed a corresponding map with the label Chaco Paraguayo (you can just make it out underneath the “Paraguay” banner.) The very next year, Bolivia would “occupy” the Chaco, philatelically speaking. The battle was on! Bolivia kept laying it on, reissuing its design in 1931, the year before the fighting began. Its last map stamp with the Chaco Boliviano inscription was issued in 1935, the year the two sides agreed to a cease fire.

A year earlier, Paraguay had established its philatelic claim to the Chaco, a region that constituted about 40 percent of its northern land mass. A Paraguayan stamp in 1927 (right) displayed a corresponding map with the label Chaco Paraguayo (you can just make it out underneath the “Paraguay” banner.) The very next year, Bolivia would “occupy” the Chaco, philatelically speaking. The battle was on! Bolivia kept laying it on, reissuing its design in 1931, the year before the fighting began. Its last map stamp with the Chaco Boliviano inscription was issued in 1935, the year the two sides agreed to a cease fire. Postal officials in Paraguay countered the Bolivian affront with more stamps, this one at right a bit larger than the offending ones, with a map that clearly labeled the disputed territory as Chaco Paraguayo. To drive home the point, the stamp carried a legend at the bottom: Ha sido, es y sera (“Has been, is and will be”). As if that weren’t clear enough, the message continued on a pair of shields: El Chaco Boreal / Del Paraguay. (boreal means “northern”)

Postal officials in Paraguay countered the Bolivian affront with more stamps, this one at right a bit larger than the offending ones, with a map that clearly labeled the disputed territory as Chaco Paraguayo. To drive home the point, the stamp carried a legend at the bottom: Ha sido, es y sera (“Has been, is and will be”). As if that weren’t clear enough, the message continued on a pair of shields: El Chaco Boreal / Del Paraguay. (boreal means “northern”) In the bitter fighting, Paraguay eventually took control of much of the territory, and a ceasefire was reached in 1935. But it was not until 1938 that a truce was negotiated and signed. The agreement awarded Paraguay about two-thirds of the Chaco. That nation followed up with a series of self-congratulatory stamps celebrating the accord. One stamp (see right) really rubbed it in: A map pointedly emphasized Paraguay’s territorial dominance, and was accompanied by a suitably smarmy quotation, “Una paz honoroso vale mas que todos los triunfos militaries” (“An honorable peace is worth more than all the military triumphs”).

In the bitter fighting, Paraguay eventually took control of much of the territory, and a ceasefire was reached in 1935. But it was not until 1938 that a truce was negotiated and signed. The agreement awarded Paraguay about two-thirds of the Chaco. That nation followed up with a series of self-congratulatory stamps celebrating the accord. One stamp (see right) really rubbed it in: A map pointedly emphasized Paraguay’s territorial dominance, and was accompanied by a suitably smarmy quotation, “Una paz honoroso vale mas que todos los triunfos militaries” (“An honorable peace is worth more than all the military triumphs”).

lower stamp depicts a dreaded U-Boat slicing its way through the sea under a corona of sunbeams, while a ship burns in the background — presumably its enemy prey. British? American?

lower stamp depicts a dreaded U-Boat slicing its way through the sea under a corona of sunbeams, while a ship burns in the background — presumably its enemy prey. British? American?

helicopter clearly labeled, “U.S. Army.” In the stamp below it, a U.S. B-52 explodes, hit by ship-to-air artillery, while another flaming jet in the background plummets to the Earth.

helicopter clearly labeled, “U.S. Army.” In the stamp below it, a U.S. B-52 explodes, hit by ship-to-air artillery, while another flaming jet in the background plummets to the Earth.

its place in the imperial constellation.

its place in the imperial constellation.

Eisenhower.

Eisenhower.

These stamps have nothing to do with Fujeira or Sierra Leone, any more than the sets of French classical painting on stamps from the Arab world or Central Africa. Is that a philatelic crime? At least a shade unethical?

These stamps have nothing to do with Fujeira or Sierra Leone, any more than the sets of French classical painting on stamps from the Arab world or Central Africa. Is that a philatelic crime? At least a shade unethical?

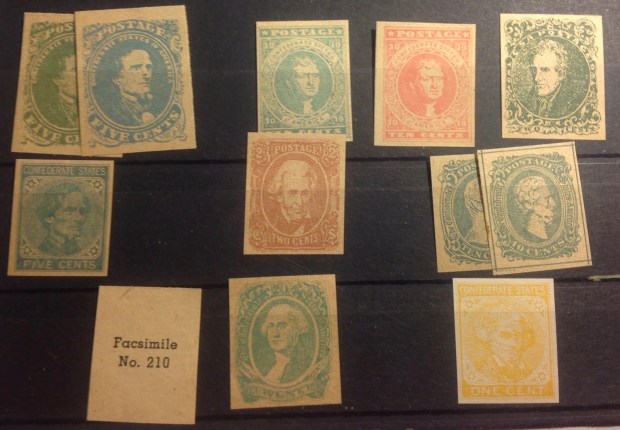

MacIntosh agreed to label the stamps “Facsimile” and number his fakes. At right, for comparison purposes, I offer an example of the actual 10-cent Jefferson Davis profile stamp of 1863. I know it’s genuine because it was used on a cover, and passed down to me in my collection. Am I really sure? Well, look closely: the engraving itself is distinctive (the cheap imitation of the 10-cent stamp above, which is in the second row, far right, is lithographed, if I’m not mistaken.)

MacIntosh agreed to label the stamps “Facsimile” and number his fakes. At right, for comparison purposes, I offer an example of the actual 10-cent Jefferson Davis profile stamp of 1863. I know it’s genuine because it was used on a cover, and passed down to me in my collection. Am I really sure? Well, look closely: the engraving itself is distinctive (the cheap imitation of the 10-cent stamp above, which is in the second row, far right, is lithographed, if I’m not mistaken.)