This is the gist of a talk I just gave at the Syracuse Stamp Club. Vice President Dan invited me to focus on Congo stamps. I already had presented once on this subject, but Dan said he was still confused about the “different Congos” and which stamps went with which. I readily agreed to take on this intriguing topic. I assembled a group of digital images of stamp “signposts,” mostly from my collection, to help navigate the turbulent currents and tributaries of Congo-related philately. My presentation took the form of a quiz: Look at the stamp projected on the screen and identify or guess which “Congo” it came from. Also: see if you can stump the presenter with your questions. (I don’t know everything about Congo stamps!) Comments afterwards from the audience of 20-plus indicated they liked the program, so it seemed worthwhile to recapture some of it for the blog. On with the show — a quick narrative guide through 42 slides.

1. Here is the first set of stamps issued in what would become the Belgian Congo. They picture King Leopold II of Belgium, and look a lot like Belgian stamps of the period. You can just make out the tiny writing, “Etat Ind du Congo.” That means “independent state of the Congo” — though it was anything but! What it really meant was that King Leopold was “independent” of accountability to his own government or anyone else but God. He ran this vast colony as his private fiefdom. Though he never set foot in the Congo, he micromanaged the place from his palace in Brussels, built a vast and exotic Congo museum complex in his royal gardens. While he mouthed platitudes about Christianity, civic progress, development and moral uplift, he ruthlessly suppressed indigenous populations. He exploited the country’s ivory, rubber and other resources for his own profit. He also issued stamps for his “independent” state. This set of five stamps catalogues at several hundred dollars, largely due to the rare 5 franc value.

1. Here is the first set of stamps issued in what would become the Belgian Congo. They picture King Leopold II of Belgium, and look a lot like Belgian stamps of the period. You can just make out the tiny writing, “Etat Ind du Congo.” That means “independent state of the Congo” — though it was anything but! What it really meant was that King Leopold was “independent” of accountability to his own government or anyone else but God. He ran this vast colony as his private fiefdom. Though he never set foot in the Congo, he micromanaged the place from his palace in Brussels, built a vast and exotic Congo museum complex in his royal gardens. While he mouthed platitudes about Christianity, civic progress, development and moral uplift, he ruthlessly suppressed indigenous populations. He exploited the country’s ivory, rubber and other resources for his own profit. He also issued stamps for his “independent” state. This set of five stamps catalogues at several hundred dollars, largely due to the rare 5 franc value.

2. The Congo may have been a vassal state of a callous ruler — Joseph Conrad used it as the locus of his haunting novel, “Heart of Darkness” — but King Leopold did manage to put out some pretty stamps. Look at this lovely two-color engraving from the 1890s of the growing town that was to become Leopoldville.

2. The Congo may have been a vassal state of a callous ruler — Joseph Conrad used it as the locus of his haunting novel, “Heart of Darkness” — but King Leopold did manage to put out some pretty stamps. Look at this lovely two-color engraving from the 1890s of the growing town that was to become Leopoldville.

3. By 1906, King Leopold’s Congo was such an embarrassment to the “civilized world,” thanks to the investigations and reports of reformers like Roger Casement and Edmond Morel, that the Belgian government had to step in and taking control. The “independent” Congo henceforth became the “Belgian Congo.” By the time the old king died in 1909, the regime in Brussels had issued a set of stamps obliterating the old title with the new name: “Congo Belge.” There are two sets: In one, the stamps are hand-cancelled; the others, as in this illustration, were machine-cancelled, worth considerably less.

4. The powers-that-be quickly followed up with another short set, using the same designs

as the earlier series, but with the new name. This engraving shows the busy port of Matadi. But there was a festering problem: Since Belgium is a bilingual nation — French and Flemish — the French-only stamps were a political irritant.

5. Belgian stamps were bilingual by the 1890s, so the  Belgian Congo had to accommodate the proud and vocal — and touchy — Flemish constituency as well. Here is the result. It turned out to be relatively easy to keep the central images of the original set and redesign the borders to make room for “Belgisch Congo” as well as the French name. This charming two-color engraving depicts the railroad from Leo to Matadi, at the time a considerable engineering feat. Alas, the mammoth construction project took its toll in lives, most of them Congolese.

Belgian Congo had to accommodate the proud and vocal — and touchy — Flemish constituency as well. Here is the result. It turned out to be relatively easy to keep the central images of the original set and redesign the borders to make room for “Belgisch Congo” as well as the French name. This charming two-color engraving depicts the railroad from Leo to Matadi, at the time a considerable engineering feat. Alas, the mammoth construction project took its toll in lives, most of them Congolese.

6. The “bilingual imperative” now in place for Belgian Congo stamps did have some awkward moments. Take this set from the 1940s — or rather, two sets from the 1940s. The nicely engraved stamps were identical in every way — except that in one set, the country’s name was printed first in French, then in Flemish; in the other set, the names were reversed.

7. This awkward practice continued, off and on, into the 1950s. This double set featuring Belgian King Baudouin was issued five years before independence.

8. What’s this? A set from 1930s Belgian Congo, overprinted “USA Airmail”? With denominations in U.S. cents? What gives? I wish I had a satisfactory answer for you, but I don’t. Were Americans really a presence in the Belgian Congo? Was this overprint used at the U.S. embassy, or by troops passing through? So far, it remains a mystery to me. Whatever its provenance, the set isn’t expensive to buy.

8. What’s this? A set from 1930s Belgian Congo, overprinted “USA Airmail”? With denominations in U.S. cents? What gives? I wish I had a satisfactory answer for you, but I don’t. Were Americans really a presence in the Belgian Congo? Was this overprint used at the U.S. embassy, or by troops passing through? So far, it remains a mystery to me. Whatever its provenance, the set isn’t expensive to buy.

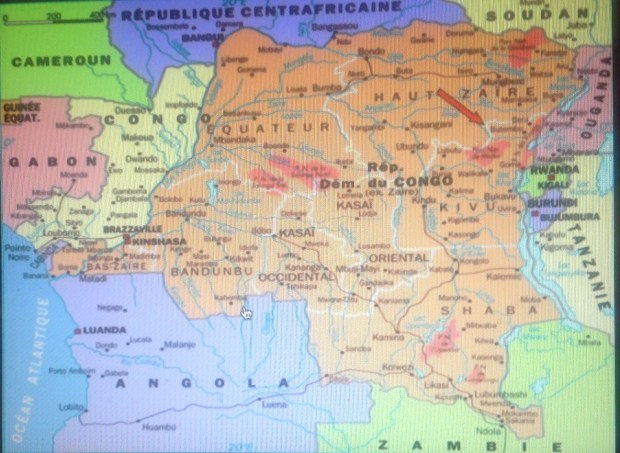

9. Right about now would be a good time to introduce a map of the Congo, so you can get geographical idea of the stamp-issuing areas represented in coming slides. I lived in the Congo from 1962 to 1964, when I was 14-16 years old. My father was a diplomat, and we lived in Leopoldville, the capital city in western Congo, not far from the Atlantic Ocean — or the Equator. The areas I will be discussing up to 1,000 miles from Leopoldville, in central and eastern Congo — Katanga in the southeast, Kasai in the center, Stanleyville in the northeast. Then there is Ruanda-Urundi, a separate Belgian territory bordering on the Congo’s eastern frontier. I also will have things to say about the territory around Leopoldville — both south and north. This map highlights the divisions of the “crisis years” between 1960 and 1964. This refers to the breakaway republics of Katanga and South Kasai, as well as so-called Simba uprisings around Albertville (northern Katanga) and Stanleyville (center-north), all of which produced postage stamps.

10. This stamp marking the secession of Katanga shows a lot of gall. Not only does it co-opt a stamp from the “mother nation” of the Congo, it blots out that nation’s independence day with its own date, cleverly leaving “1960” uncovered. It also leaves alone the banner “Independance” (inedependence), but obliterates “Congo” with the audacious overprint “de L’Etat du Katanga” (of the state of Katanga). The essential illogic of this stamp, however, is that it depicts the whole nation of Congo and doesn’t even identify the rebel province that is declaring its independence.

10. This stamp marking the secession of Katanga shows a lot of gall. Not only does it co-opt a stamp from the “mother nation” of the Congo, it blots out that nation’s independence day with its own date, cleverly leaving “1960” uncovered. It also leaves alone the banner “Independance” (inedependence), but obliterates “Congo” with the audacious overprint “de L’Etat du Katanga” (of the state of Katanga). The essential illogic of this stamp, however, is that it depicts the whole nation of Congo and doesn’t even identify the rebel province that is declaring its independence.

11. Here’s a semi-postal stamp from Katanga picturing the renegade leader, Moise Tshombe (who I once met, by the way, but that’s another story). It features the copper crosses that are emblems Katanga, literal currency at one time, and a key source of the region’s economic well-being, such as it was.

11. Here’s a semi-postal stamp from Katanga picturing the renegade leader, Moise Tshombe (who I once met, by the way, but that’s another story). It features the copper crosses that are emblems Katanga, literal currency at one time, and a key source of the region’s economic well-being, such as it was.

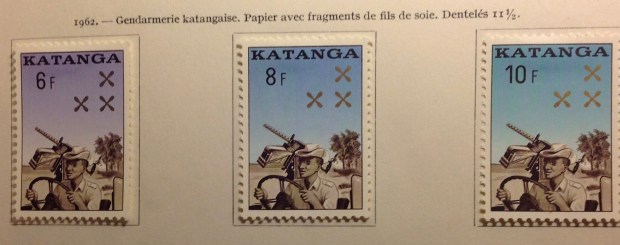

12. This Katanga set seemed quite modern for 1961. The indigenous bas-relief sculpture has primitive charm, though the characters do bear some resemblance to “Mr. Bill,” the hapless, creepy clay figure from early “Saturday Night Live.”

12. This Katanga set seemed quite modern for 1961. The indigenous bas-relief sculpture has primitive charm, though the characters do bear some resemblance to “Mr. Bill,” the hapless, creepy clay figure from early “Saturday Night Live.”

13. I include this cover of Katanga stamps, all of them overprinted Belgian Congo stamps, because I am quite proud to display such a rich sample of postally used examples from a country that only existed for a couple of years. I expect it is worth as much as $20 or more — if you can find a buyer for this obscure stuff.

13. I include this cover of Katanga stamps, all of them overprinted Belgian Congo stamps, because I am quite proud to display such a rich sample of postally used examples from a country that only existed for a couple of years. I expect it is worth as much as $20 or more — if you can find a buyer for this obscure stuff.

14. These 1950s-era definitive stamps from India are familiar enough. But what’s with the “Congo” overprint? Here’s what: During the troubles in Katanga, the United Nations stepped up with peacekeeping troops to try to straighten things out. There also were troops from Sweden, Canada and Ireland, but the Indians seem to be the only ones who issued their own stamps — or rather, their own stamps overprinted “U.N. Force (India) Congo.” Was it national pride? Was there a practical purpose, i.e., to provide the troops with stamps to use on letters home? If so, where are the covers with cancelled copies of these stamps? I’ve never seen one. If they exist, such philatelic oddities must be quite rare and valuable. India also overprinted this set for troops serving the United Nations in Korea (1953), Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam (1950s) and Gaza (1965).

14. These 1950s-era definitive stamps from India are familiar enough. But what’s with the “Congo” overprint? Here’s what: During the troubles in Katanga, the United Nations stepped up with peacekeeping troops to try to straighten things out. There also were troops from Sweden, Canada and Ireland, but the Indians seem to be the only ones who issued their own stamps — or rather, their own stamps overprinted “U.N. Force (India) Congo.” Was it national pride? Was there a practical purpose, i.e., to provide the troops with stamps to use on letters home? If so, where are the covers with cancelled copies of these stamps? I’ve never seen one. If they exist, such philatelic oddities must be quite rare and valuable. India also overprinted this set for troops serving the United Nations in Korea (1953), Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam (1950s) and Gaza (1965).

15. Here is another overprinted set, this one involving the Belgian Congo flowers set of 1952-3. The set became the first issued by the independent nation, which was overprinted “Congo.” Here the same colonial flowers set was used for the breakaway republic of South Kasai, a renegade central province. This was only a half-hearted rebellion — South Kasai never broke relations completely with the central government, and President Albert Kalonji retained his seat in the Congolese parliament.

15. Here is another overprinted set, this one involving the Belgian Congo flowers set of 1952-3. The set became the first issued by the independent nation, which was overprinted “Congo.” Here the same colonial flowers set was used for the breakaway republic of South Kasai, a renegade central province. This was only a half-hearted rebellion — South Kasai never broke relations completely with the central government, and President Albert Kalonji retained his seat in the Congolese parliament.

16. Here are the rest of the stamps issued by South Kasai, including original designs, i.e., not overprinted Congo stamps. The rebellion petered out in a few months, and Albert Kalonji, (pictured here) the president of the short-lived state, ended up in exile — but alive.

16. Here are the rest of the stamps issued by South Kasai, including original designs, i.e., not overprinted Congo stamps. The rebellion petered out in a few months, and Albert Kalonji, (pictured here) the president of the short-lived state, ended up in exile — but alive.

17. The transition from colony to independence was haphazard in the Congo — socially, politically, economically — and philatelically. There were missing or misplaced overprints and surcharges, upside-down printings (“inverts”) and other varieties. As a 15-year-old stamp collector In 1964, I was able to buy stamps at the downtown Bureau de Poste to create a cover using six different versions of the original 6.50-frank stamp of the animal series depicting two leaping impala.

Top row, left to right: 1. the original stamp, issued in 1959; 2. the same stamp, overprinted “CONGO” in red, issued 1960; 3. ditto, overprinted in black.

Lower row, left to right: 1. ditto, with a silver surcharge “5F” and red overprint, 1964; 2. ditto, with silver surcharge and black overprint; 3. finally, with a silver surcharge as well as a silver bar behind the black inscription “Republique du Congo.”

I created another cov er with five different varieties of the 20-centime stamps from the same animal series, featuring a rhinoceros. Can you pick out the differences. The last item, lower right, is a most peculiar error. Let me explain:

er with five different varieties of the 20-centime stamps from the same animal series, featuring a rhinoceros. Can you pick out the differences. The last item, lower right, is a most peculiar error. Let me explain:

While the original Belgian Congo stamp was successfully surcharged “1F” on a silver rectangle, the “REPUBLIQUE DU CONGO” overprint is missing. This means the stamp looks for all the world like a new “Belgian Congo” stamp — issued in 1964, four years after independence! (This stamp is not listed in my Scott catalogue.)

18. Here is a Congo stamp featuring Patrice Lumumba, the controversial first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1960. Only the stamp is not from that Congo, but from the “other” Congo — the former French Congo, now the “Popular Republic of the Congo.” Lumumba has never appeared on a stamp from his own country — not a big surprise, since he was assassinated with the acquiescence or connivance of Congolese leaders Joseph Mobutu, Joseph Kasavubu and Moise Tshombe. It was up to other African nations like the neighboring Congo, ruled by Marxists and self-styled Marxists over the years since its own independence, to memorialize the mercurial Lumumba.

18. Here is a Congo stamp featuring Patrice Lumumba, the controversial first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1960. Only the stamp is not from that Congo, but from the “other” Congo — the former French Congo, now the “Popular Republic of the Congo.” Lumumba has never appeared on a stamp from his own country — not a big surprise, since he was assassinated with the acquiescence or connivance of Congolese leaders Joseph Mobutu, Joseph Kasavubu and Moise Tshombe. It was up to other African nations like the neighboring Congo, ruled by Marxists and self-styled Marxists over the years since its own independence, to memorialize the mercurial Lumumba.

19. Here are stamps from early in the former Belgian Congo’s independence years. They honor Dag Hammerskjold, the UN leader killed in a plane crash in September, 1960 while trying to mediate the standoff between Katanga and the mother Congo. The overprint reproduces a slogan from the short-lived administration of Congolese Prime Minister Cyrille Adoula — “paix, travail, austerite” (peace, work, thrift).In 1962, the earnest, honest Adoula seemed to hold out hope for a better future — but his tenure was cut short by events and plots.

Kasavubu

20. Congo’s president from 1960 to 1965 was Joseph Kasavubu, a wily politician from an important tribal family. He managed to hang on through the Congo’s most turbulent years, only to be dismissed into retirement after a young colonel named Joseph Mobutu took over in 1965.

A young Mobutu

21. After Kasavubu fired Adoula as prime minister in 1964, he called on Moise Tshombe, the exiled former leader of the Katanga breakaway province, to try and bring order to the Congo itself. This was not quite like Jefferson Davis being invited to take over after Abraham Lincoln, but you get the idea. Tshombe lasted about a year, whereupon Mobutu and the army stepped in. He rapidly consolidated his power and proceeded to rule the Congo for the next 30 years with a combination of harshness, violence, cruelty, indifference toward his people, hypocrisy and narcissism, monumental greed and selfishness. Would you like to know how I really feel about him?

22. Mobutu’s most cynical act was his claim of “authenticity” — that he somehow embodied African values and aspirations. He renamed his country “Zaire,” in ancient tribal tradition, gave himself fancy new titles, and began to sport a walking stick and leopard-skin hat. This Zaire stamp says more than its designers may have intended. It pictures Mobutu contemplating the big diamond — loot! And what kind of guy has himself depicted on a postage stamp wearing sunglasses? Shifty!

22. Mobutu’s most cynical act was his claim of “authenticity” — that he somehow embodied African values and aspirations. He renamed his country “Zaire,” in ancient tribal tradition, gave himself fancy new titles, and began to sport a walking stick and leopard-skin hat. This Zaire stamp says more than its designers may have intended. It pictures Mobutu contemplating the big diamond — loot! And what kind of guy has himself depicted on a postage stamp wearing sunglasses? Shifty!

23. Here’s an even better likeness of Mobutu — again, probably not intended by the stamp’s designers …

24. Now for a U-turn back to 1915, folks! Back to World War I, which was being fought in Africa as well as Eurasia. Germany had maintained a colony in east Africa since the 1880s. After hostilities broke out in 1914, it didn’t take long for the English to the north and east, and the Belgians in the west, to overwhelm German East Africa’s forces. They divided the spoils: Britain “took” Tanganyika, and the Belgians moved into what is today Rwanda and Burundi (see maps, above and below). The first stamps from these countries were hand-overprints on the current Belgian Congo pictorial set, like this one. These stamps are quite rare. Mine cost $29.85. It catalogues for much more than that. My scribbled note “authenticated” means the stamp carries the desired mark on the back. (I guess there are counterfeits of this rare set.)

24. Now for a U-turn back to 1915, folks! Back to World War I, which was being fought in Africa as well as Eurasia. Germany had maintained a colony in east Africa since the 1880s. After hostilities broke out in 1914, it didn’t take long for the English to the north and east, and the Belgians in the west, to overwhelm German East Africa’s forces. They divided the spoils: Britain “took” Tanganyika, and the Belgians moved into what is today Rwanda and Burundi (see maps, above and below). The first stamps from these countries were hand-overprints on the current Belgian Congo pictorial set, like this one. These stamps are quite rare. Mine cost $29.85. It catalogues for much more than that. My scribbled note “authenticated” means the stamp carries the desired mark on the back. (I guess there are counterfeits of this rare set.)

25. Here is the image of a stamp from the first set of “Ruanda,” also in 1916. It’s captured from an Internet screen, and is on sale for “just” $400! That’s a rare stamp!

26. The reason the Ruanda and Urundi stamps are so valuable is that so few were issued. They were soon replaced by a set with this busy overprint — in two languages. The inscription in French and Flemish reads “German East Africa: Belgian Occupation.” The lettering partially obscures the delicate engraved designs. Aesthetically, overprints are ugly, marring the appearance of a stamp. In this case, postal authorities might as well have printed the names on blank paper!

27. How about this one — an overprint on top of an overprint? You should be able to make out a faint hand-stamp “Tabora,” above the black line rising from left to right. The Scott catalogue says these local overprints were not authorized, and assigns them no value. This item from an Internet image was on sale for a cool $99 — too rich for my wallet.

28. How about this item? It’s really not fair for the stamp designers to be so cagey. You can make out that it’s a Belgian Congo stamp, or at least was one originally. Then there’s a red cross and a printed number, presumably designating a charitable contribution of one franc on top of the stamp’s one-franc value. That’s decipherable. So is this a Congo stamp, or what? And what the heck is “A.O.”? For answers, you need a philatelist, or historian, or at least someone with a Scott catalogue who knows where to look. Then you would learn that “A.O.” stands for Afrique Orientale — East Africa. This is in fact another stamp from the Belgian occupation of Ruanda and Burundi — which in 1922 became the Belgian mandated territory of Ruanda-Urundi. One wonders how a stamp like this would be received by the indigenous population. Would they pay the extra franc for the Red Cross? Or as some philatelists suggest, did most stamps like this one (which aren’t that pricey today) never even reach post offices, but rather go right to collectors?

29. The first stamps of Ruanda-Urundi were overprints of a 1920s definitive set from the neighboring Belgian Congo. I suppose it would be a stretch to call them stamps from the Congo, though the name is on them.

29. The first stamps of Ruanda-Urundi were overprints of a 1920s definitive set from the neighboring Belgian Congo. I suppose it would be a stretch to call them stamps from the Congo, though the name is on them.

30. Here is a beauty from the first set inscribed with the name Ruanda-Urundi, in the 1940s — a handsome portrait, and a fine example of the engraver’s and colorist’s art.

31. This stamp commemorating the Olympic Games came out just as the Congo was preparing for its independence day June 30. The set shares the designs with last issue from the Belgian Congo. Ruanda-Urundi remained tied to Belgium for another year before splitting into the Kingdom of Burundi and the Republic of Rwanda. The extra year didn’t prepare either nation any better for independence than the devolving Congo to the east. The people of all three nations would continue to suffer, trading colonial oppression for corruption, misrule and tribal violence.

32. The first Burundi stamps carried clumsy overprints on leftover Belgian Congo stamps from the 1952-3 flower set.

33. The first Rwanda stamps bore slightly fancier overprints, still using stocks of Belgian Congo stamps, this one from the animal series of 1959.

34. Both Rwanda and Burundi soon were issuing stamps of their own design. This one includes a portrait of Burundi’s king, who soon enough would be sent packing.

35. Before I bring you more or less up to date, a quick history lesson about other “Congo” stamps. Here’s one from the 1900s inscribed “Congo Francais” — French Congo. Now look at the next image.

36. These two stamps are inscribed “Moyen Congo” — Middle Congo — along with the name above, “Republique Francaise.” Why Congo and Middle Congo? Aren’t they both French territory? What’s the difference? Does it matter? Indeed it does. The original French Congo overlaps with modern-day Gabon, a small nation located along the west coast of Africa, north of the Congo. Middle Congo covered a much larger territory across the Congo river from the Belgian territory.

37. Middle Congo eventually took over from French Congo, and the territory issued stamps into the 1930s, when it joined French Equatorial Africa. The first regional issues included this overprint from Middle Congo. Upon reaching independence, a large part of Middle Congo unfortunately was dubbed the republic of the Congo. The fact that there are two Congo republics across the Congo River from each other has created decades of confusion, helping to make this slide show necessary!

37. Middle Congo eventually took over from French Congo, and the territory issued stamps into the 1930s, when it joined French Equatorial Africa. The first regional issues included this overprint from Middle Congo. Upon reaching independence, a large part of Middle Congo unfortunately was dubbed the republic of the Congo. The fact that there are two Congo republics across the Congo River from each other has created decades of confusion, helping to make this slide show necessary!

38. Finally, one more “Congo” in this tangled philatelic history. The stamp pictured here was issued in 1914, and represents a colonial territory of Portugal that straddles the western “lip” of the then-Belgian Congo that extends to the south Atlantic ocean. This small “Congo” territory gave the Portuguese access to the Congo river delta. Portugal also controlled Angola, directly to the south of Belgian Congo. (see maps). While the Portuguese only used the name “Congo” until 1915, it kept control of the territory as part of Angola until independence in 1975. Today it is the free Angolan province of Cabinda, still straddling the northern border of the Congo. There is an independence movement in this tiny province. There also are stirrings from others in the region who dream of resurrecting the ancient “Kongo” kingdom. This unlikely development would only happen if land is ceded from four countries that mistrust each other — Angola, both Congos and Gabon. A final reflection: I wonder what the indigeneous population thought when they first saw this stamp back i 1914, which depicts a fierce-looking caucasian (actually the harvest goddess Ceres), wielding what could be a machete …

38. Finally, one more “Congo” in this tangled philatelic history. The stamp pictured here was issued in 1914, and represents a colonial territory of Portugal that straddles the western “lip” of the then-Belgian Congo that extends to the south Atlantic ocean. This small “Congo” territory gave the Portuguese access to the Congo river delta. Portugal also controlled Angola, directly to the south of Belgian Congo. (see maps). While the Portuguese only used the name “Congo” until 1915, it kept control of the territory as part of Angola until independence in 1975. Today it is the free Angolan province of Cabinda, still straddling the northern border of the Congo. There is an independence movement in this tiny province. There also are stirrings from others in the region who dream of resurrecting the ancient “Kongo” kingdom. This unlikely development would only happen if land is ceded from four countries that mistrust each other — Angola, both Congos and Gabon. A final reflection: I wonder what the indigeneous population thought when they first saw this stamp back i 1914, which depicts a fierce-looking caucasian (actually the harvest goddess Ceres), wielding what could be a machete …

39. Now, to start wrapping things up. Mobutu finally was forced out of the country in the mid-1990s, decamping to his European mansions, where he died soon after, having precious little time to enjoy the estimated $15 billion he st0le from his country. In 1997, in an act of embarrassment, or wishful amnesia, or spite, the powers-that-be changed the country’s name back to Republic of the Congo. This did not portend happier times for the much-abused Congolese people, alas. Even though Mobutu was gone, the country was worse than bankrupt, and misrule continued under Laurent Kabila and then his son, Joseph Kabila. This stamp captures the ethos of the post-Mobutu  era — “Zaire”: is blotted out with an ugly black rectangle. The country’s name underneath is an almost-indeciperhable “Rep Dem du Congo.” There is a new value, with the old one covered by another black box. A vulture or hawk perches menacingly amid these dark blots. The eBay seller wanted $29.99 for this odd, apparently unlisted stamp, acknowledging that it might be bogus.

era — “Zaire”: is blotted out with an ugly black rectangle. The country’s name underneath is an almost-indeciperhable “Rep Dem du Congo.” There is a new value, with the old one covered by another black box. A vulture or hawk perches menacingly amid these dark blots. The eBay seller wanted $29.99 for this odd, apparently unlisted stamp, acknowledging that it might be bogus.

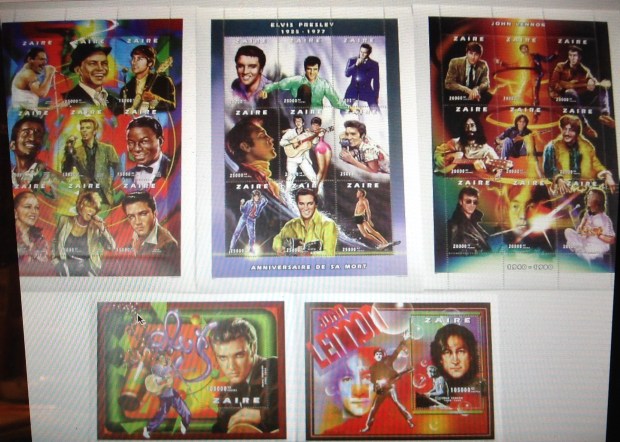

40. As it turns out, the Congo had to contend with a number of bogus stamps issued in 1997. These slick, multicolored philatelic items, still carrying the name “Zaire,” commemorate folks who had nothing to do with the Congo, like John Lennon, Frank Sinatra and Elvis. The stamps were officially declared illegal by Congolese postal authorities, who alerted the Philatelic Webmasters Organization. This group collaborates with the Universal Postal Union to call out spurious issues. The postmaster in Kinshasa identified “a certain number of philatelic products still printed with the country’s old name (Zaire).” These stamps would not be admitted for sale or use in the Congo, the note said. You can still find these fake stamps for sale on eBay. Buyer, beware!

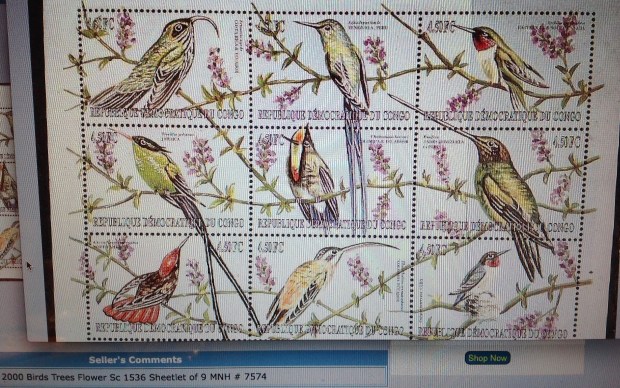

41. So we come to the end of this slide show, with an image of an authentic issue of stamps from the modern-day Democratic Republic of the Congo. Pretty stamps, eh? Don’t be fooled. There’s nothing pretty about the way Congo is being run today. I wish I could say otherwise.

41. So we come to the end of this slide show, with an image of an authentic issue of stamps from the modern-day Democratic Republic of the Congo. Pretty stamps, eh? Don’t be fooled. There’s nothing pretty about the way Congo is being run today. I wish I could say otherwise.

42. The Congo today. Note the name changes of provinces, the location of the Angolan province of Cabinda in the far west, and Rwanda and Burundi in the east.

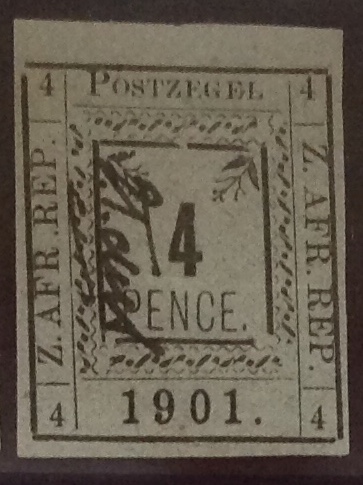

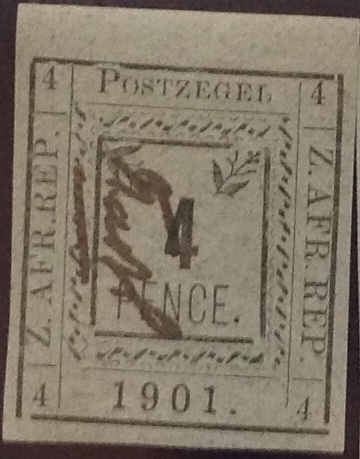

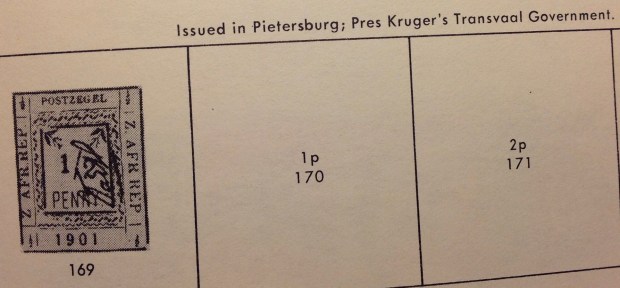

This thrilling selection of stamps arrived in the mail the other day, in a small flat package from South Africa. The stamps are from 1901, during the last days of the South African Republic (ZAR) based in Pietersburg (Transvaal), where tough, stubborn old Paul Kruger concluded his decades-long conflict with the British and dominance of black Africans. Much blood was shed and misery visited on the people before Kruger’s forces were defeated. Kruger’s strong convictions, military and political leadership

This thrilling selection of stamps arrived in the mail the other day, in a small flat package from South Africa. The stamps are from 1901, during the last days of the South African Republic (ZAR) based in Pietersburg (Transvaal), where tough, stubborn old Paul Kruger concluded his decades-long conflict with the British and dominance of black Africans. Much blood was shed and misery visited on the people before Kruger’s forces were defeated. Kruger’s strong convictions, military and political leadership

envelopes. Here is what the contents look like, just as they spilled out. Dealers and experienced collectors know how to protect and ship stamps. It’s not hard. I don’t recall ever receiving a stamp damaged in transit. The only complaint I have is sometimes, a package will include sticky tape in close proximity to a stamp, which to me is a no-no.

envelopes. Here is what the contents look like, just as they spilled out. Dealers and experienced collectors know how to protect and ship stamps. It’s not hard. I don’t recall ever receiving a stamp damaged in transit. The only complaint I have is sometimes, a package will include sticky tape in close proximity to a stamp, which to me is a no-no. The main event, however, is the handsome 1878-80 Transvaal Victoria set — five values in all, missing only the 1/2d and the 2 shilling. I admit they are not all in great shape. Some are missing perforations, the centering is not great, and one stamp has a thin spot on the back. Yet I still was willing to pay for the set. I mean, think about it: The stamps are nearly 140 years old. They started out being bought at a ZAR/Transvaal post office counter, stuck to an envelope and sent through the mail, involving carriages, trains and sailing ships, possible all three. So what if a couple of them are what is called “space fillers” — that is, they will never have much value because of their flaws. I go back to the emblematic significance of these stamps. They are artifacts from a long-ago time and place of imperial Britain asserting itself over the Boers. For a while, British rule would be fragile and temporary in a state that continued to be bargained for and fought over — as though it actually belonged to either side.

The main event, however, is the handsome 1878-80 Transvaal Victoria set — five values in all, missing only the 1/2d and the 2 shilling. I admit they are not all in great shape. Some are missing perforations, the centering is not great, and one stamp has a thin spot on the back. Yet I still was willing to pay for the set. I mean, think about it: The stamps are nearly 140 years old. They started out being bought at a ZAR/Transvaal post office counter, stuck to an envelope and sent through the mail, involving carriages, trains and sailing ships, possible all three. So what if a couple of them are what is called “space fillers” — that is, they will never have much value because of their flaws. I go back to the emblematic significance of these stamps. They are artifacts from a long-ago time and place of imperial Britain asserting itself over the Boers. For a while, British rule would be fragile and temporary in a state that continued to be bargained for and fought over — as though it actually belonged to either side. early American stamps — a rare multiple of three of the first three-cent issue (circa 1852), featuring a side profile bust of George Washington. I examined them closely, thrilled to realize they had been sitting in that book for more than 150 years. They were still in pristine condition, as fresh as the day Daniel’s ancestor bought them at a post office for nine cents. Well, he probably bought at least four of them (for 12 cents), cut out one of them, licked the gum on the back and pasted the stamp to a letter, then stored the others for a future use that never arrived..

early American stamps — a rare multiple of three of the first three-cent issue (circa 1852), featuring a side profile bust of George Washington. I examined them closely, thrilled to realize they had been sitting in that book for more than 150 years. They were still in pristine condition, as fresh as the day Daniel’s ancestor bought them at a post office for nine cents. Well, he probably bought at least four of them (for 12 cents), cut out one of them, licked the gum on the back and pasted the stamp to a letter, then stored the others for a future use that never arrived..

3d. blue from St. Helena, picturing the badge of the colony, completes my long set of the George VI definitives from the 1930s (see illustration).

3d. blue from St. Helena, picturing the badge of the colony, completes my long set of the George VI definitives from the 1930s (see illustration). The one-pound stamp from Cyprus completes my George VI set from that country, same era. For a description of the pleasure that awaits in adding these two stamps to complete the sets on the pages of my British Africa and British America albums, please refer to a post in January 2017 on the joys of “filling spaces.”

The one-pound stamp from Cyprus completes my George VI set from that country, same era. For a description of the pleasure that awaits in adding these two stamps to complete the sets on the pages of my British Africa and British America albums, please refer to a post in January 2017 on the joys of “filling spaces.”

ia and across the Pacific.

ia and across the Pacific.

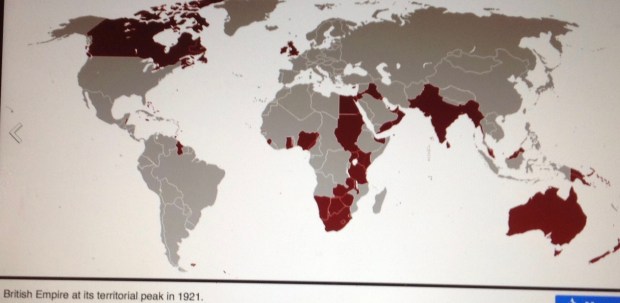

The statistical apex of territorial claims in the British Empire actually would not come until 1921. At that time, the empire had influence over 33.7 million square kilometers. Half of the globe’s dry land was “theirs in fee.” The empire’s population of more than 458 million souls constituted one-fifth of the Earth’s people.

The statistical apex of territorial claims in the British Empire actually would not come until 1921. At that time, the empire had influence over 33.7 million square kilometers. Half of the globe’s dry land was “theirs in fee.” The empire’s population of more than 458 million souls constituted one-fifth of the Earth’s people. Pictured here is an example of the stamps that were in circulation in 1897 or thereabouts, issued for use in far-flung precincts of the British Empire, all bearing a likeness of Queen Victoria. As you observe the similarities and subtle differences in the portraits and borders, explored in the next commentary, you can get a sense of how these stamps helped to draw together the British Empire; how they created an identity, a self-image, sustaining a unity of purpose, a commitment to stability and civic order, even pride in being part of this global enterprise. As you contemplate this mosaic of empire reflecting the image of an aging queen, consider these lines from Sir William Morris’s ode:

Pictured here is an example of the stamps that were in circulation in 1897 or thereabouts, issued for use in far-flung precincts of the British Empire, all bearing a likeness of Queen Victoria. As you observe the similarities and subtle differences in the portraits and borders, explored in the next commentary, you can get a sense of how these stamps helped to draw together the British Empire; how they created an identity, a self-image, sustaining a unity of purpose, a commitment to stability and civic order, even pride in being part of this global enterprise. As you contemplate this mosaic of empire reflecting the image of an aging queen, consider these lines from Sir William Morris’s ode:

Great Britain was the seat of empire, and GB never had to put its name on its stamps — because it was first, in 1840. (Can you believe it?) This set — the Queen Victoria Jubilee Issue — was released in 1887, with added values in later years. It set the standard for issues in colonies around the world. I include two stamps from the set,with considerable variations — if you can make them out under the heavy cancels. I particularly like the royal purple of the 2 1/2 d.

Great Britain was the seat of empire, and GB never had to put its name on its stamps — because it was first, in 1840. (Can you believe it?) This set — the Queen Victoria Jubilee Issue — was released in 1887, with added values in later years. It set the standard for issues in colonies around the world. I include two stamps from the set,with considerable variations — if you can make them out under the heavy cancels. I particularly like the royal purple of the 2 1/2 d.

Early Victorian stamp design similarities — 1850s-1860s. Most British stamps from Victorian era originated with the cameo portrait of Princess Victoria created by William Wyon in 1834, pictured here. That image appeared on a medal commemorating the new queen’s visit to London in 1837. It also became the basis for the world’s first stamp — the “Penny Black” of 1840 (see below). The stamp’s designer, Sir Rowland Hill, picked the rough sketch by Henry Corbould (I’m still looking for that sketch), and engravers Charles Heath and his son Frederick

Early Victorian stamp design similarities — 1850s-1860s. Most British stamps from Victorian era originated with the cameo portrait of Princess Victoria created by William Wyon in 1834, pictured here. That image appeared on a medal commemorating the new queen’s visit to London in 1837. It also became the basis for the world’s first stamp — the “Penny Black” of 1840 (see below). The stamp’s designer, Sir Rowland Hill, picked the rough sketch by Henry Corbould (I’m still looking for that sketch), and engravers Charles Heath and his son Frederick  produced the stamp. The image, subject to minor revision over the years, and illustrated by the early stamps pictured below, would remain in continuous use in successive sets issued in Great Britain and the empire until Victoria’s death in 1901.

produced the stamp. The image, subject to minor revision over the years, and illustrated by the early stamps pictured below, would remain in continuous use in successive sets issued in Great Britain and the empire until Victoria’s death in 1901.

Take a second look at the portrait in the Nova Scotia stamp, at right — the green 8 and 1/2-center from 1860 (value: a few bucks at most). On double-take, it’s clearly not based on the Chalon head. My bet is on the Winterhalter portrait of 1859, reproduced below.

Take a second look at the portrait in the Nova Scotia stamp, at right — the green 8 and 1/2-center from 1860 (value: a few bucks at most). On double-take, it’s clearly not based on the Chalon head. My bet is on the Winterhalter portrait of 1859, reproduced below.

Reality check: Here is an apparent photo-like record of the marriage of Victoria and Albert in London, Feb. 10, 1840. The close-up below is strikingly immediate, bringing you face to face with an intimate moment more than a century-and-a-half ago. … Queen Victoria looks, well, short and dumpy. She has a big nose and a receding chin. She is, well, homely. Perhaps such realistic depictions don’t do her justice. Or perhaps the engraver’s art is, well, artful. There is no mistaking her resolve in this image as she gazes at her prince. They were by all accounts a happy couple, in love and devoted to each other for the 21 years allotted them before Albert succumbed to stomach ailments and

Reality check: Here is an apparent photo-like record of the marriage of Victoria and Albert in London, Feb. 10, 1840. The close-up below is strikingly immediate, bringing you face to face with an intimate moment more than a century-and-a-half ago. … Queen Victoria looks, well, short and dumpy. She has a big nose and a receding chin. She is, well, homely. Perhaps such realistic depictions don’t do her justice. Or perhaps the engraver’s art is, well, artful. There is no mistaking her resolve in this image as she gazes at her prince. They were by all accounts a happy couple, in love and devoted to each other for the 21 years allotted them before Albert succumbed to stomach ailments and  typhoid fever. They had nine children. Victoria would continue on as queen until her death in 1901, becoming the longest-reigning British monarch in modern history — that is, until her great-great-grandaughter Elizabeth broke her record in 2015.

typhoid fever. They had nine children. Victoria would continue on as queen until her death in 1901, becoming the longest-reigning British monarch in modern history — that is, until her great-great-grandaughter Elizabeth broke her record in 2015.

were another matter. From early on, black Africans collaborated, conspired and clashed with whites, the same as would one tribe with another. Particularly vivid are stories of the sometimes nuanced relations between Boer and Zulu leaders in the 1880s and 1890s. The turn of the century brought to full flower the Boer War with the British. The pitched battles were appalling in the loss of life and limb. In comparison, the tangle of philatelic history involved will be a pleasure to try and unravel.

were another matter. From early on, black Africans collaborated, conspired and clashed with whites, the same as would one tribe with another. Particularly vivid are stories of the sometimes nuanced relations between Boer and Zulu leaders in the 1880s and 1890s. The turn of the century brought to full flower the Boer War with the British. The pitched battles were appalling in the loss of life and limb. In comparison, the tangle of philatelic history involved will be a pleasure to try and unravel.

Here are some stamps from countries I will be skipping over — like British East Africa, a “country” that first ran like a concessionary stand for imperial adventurers, developers, entrepreneurs and looters under the British. (“Light and Liberty”? Don’t make me cry …)

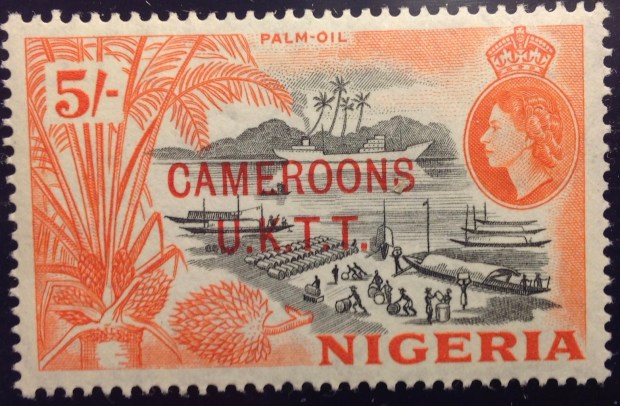

Here are some stamps from countries I will be skipping over — like British East Africa, a “country” that first ran like a concessionary stand for imperial adventurers, developers, entrepreneurs and looters under the British. (“Light and Liberty”? Don’t make me cry …) Here is a stamp from German “Kamerun,” occupied by Great Britain after World War I. The French took over much of Cameroon, in west Africa, though British influence remained. As the region was going independent in 1960s, the UK issued a set of stamps — Nigerian definitives, overprinted — for use in the Anglophone trust territories (UKTT) until their final disposition could be decided. The Scott catalogue explains what happened next: “Nos. 66-77 were withdrawn in Northern Cameroons on May 31, 1961, when that territory joined Nigeria and in Southern Cameroons Sept. 30, 1961, when that territory joined the Cameroon Federal Republic.”

Here is a stamp from German “Kamerun,” occupied by Great Britain after World War I. The French took over much of Cameroon, in west Africa, though British influence remained. As the region was going independent in 1960s, the UK issued a set of stamps — Nigerian definitives, overprinted — for use in the Anglophone trust territories (UKTT) until their final disposition could be decided. The Scott catalogue explains what happened next: “Nos. 66-77 were withdrawn in Northern Cameroons on May 31, 1961, when that territory joined Nigeria and in Southern Cameroons Sept. 30, 1961, when that territory joined the Cameroon Federal Republic.”

Africa — Belgische Bezetting.” This cluttered inscription suggests the Belgians were taking over from the Germans. But in such a case, one might ask, why still call it “German East Africa”? Was there a nationalist motive — to rub Germany’s nose in its defeat by asserting mastery over its erstwhile colony? Or was there a tacit colonial bond implied here, as though the two imperial powers were exchanging property, perhaps temporariliy, but otherwise maintaining all the imperial trappings and perquisites?

Africa — Belgische Bezetting.” This cluttered inscription suggests the Belgians were taking over from the Germans. But in such a case, one might ask, why still call it “German East Africa”? Was there a nationalist motive — to rub Germany’s nose in its defeat by asserting mastery over its erstwhile colony? Or was there a tacit colonial bond implied here, as though the two imperial powers were exchanging property, perhaps temporariliy, but otherwise maintaining all the imperial trappings and perquisites?

ts. These are costly Congo stamps, because they are so rare. Later on, stamps in the colorful definitive series of 1909 were recycled numerous times. Four of them were overprinted with the year “1921”; many were surcharged with new values. Eventually, there

ts. These are costly Congo stamps, because they are so rare. Later on, stamps in the colorful definitive series of 1909 were recycled numerous times. Four of them were overprinted with the year “1921”; many were surcharged with new values. Eventually, there  were surcharges on surcharges. Imagine being confronted with a 10-centimes stamp, surcharged 30 centimes, then handstamped 25 centimes. What gives? Now go one stamp further: What about when the “0,25” is handstamped twice? Is that a double surcharge? A misprint? A new variety? So many questions! Congo postal authorities

were surcharges on surcharges. Imagine being confronted with a 10-centimes stamp, surcharged 30 centimes, then handstamped 25 centimes. What gives? Now go one stamp further: What about when the “0,25” is handstamped twice? Is that a double surcharge? A misprint? A new variety? So many questions! Congo postal authorities  kept surcharging sets through the years, up until independence and beyond, with predictably mixed results.

kept surcharging sets through the years, up until independence and beyond, with predictably mixed results.

To get back on the philatelic track, why a “USA Detatchment” overprint on Congo stamps from the 1930s? These stamps would not have been issued during the war, since by the 1940s there was a new definitive set in circulation. A little research turned up the following scanty information: The stamps were issued in 1931 as a “private printing.” For decades, it had not been unusual for the U.S. government to dispatch “detachments” of Marines or other soldiers to guard U.S. embassies and other assets abroad. (In Cameroon, for example.) However, there was no mention of embassies issuing postage stamps for use by the troops or anyone else. Were these stamps valid in the Congo, for example as postage on mail sent home by the U.S. troops in Leopoldville? I don’t know. I have never seen any cancelled examples of these stamps, or postally used covers including them. They may well be “Cinderellas” (a term applied to postally spurious issues, which I promise to address in a future commentary). They certainly constitute an interesting historical oddity: “American” stamps, with U.S. currency denominations and “USA Airmail” overprinted on Belgian Congo stamps. There must be more to this story.

To get back on the philatelic track, why a “USA Detatchment” overprint on Congo stamps from the 1930s? These stamps would not have been issued during the war, since by the 1940s there was a new definitive set in circulation. A little research turned up the following scanty information: The stamps were issued in 1931 as a “private printing.” For decades, it had not been unusual for the U.S. government to dispatch “detachments” of Marines or other soldiers to guard U.S. embassies and other assets abroad. (In Cameroon, for example.) However, there was no mention of embassies issuing postage stamps for use by the troops or anyone else. Were these stamps valid in the Congo, for example as postage on mail sent home by the U.S. troops in Leopoldville? I don’t know. I have never seen any cancelled examples of these stamps, or postally used covers including them. They may well be “Cinderellas” (a term applied to postally spurious issues, which I promise to address in a future commentary). They certainly constitute an interesting historical oddity: “American” stamps, with U.S. currency denominations and “USA Airmail” overprinted on Belgian Congo stamps. There must be more to this story. rent definitive series, overprinted “U.N. Force (India) Congo.” This set sells for a modest sum, mint or used, though cancelled copies on postally used covers mailed in the Congo might command a higher price. (Indians must have been proud of their role as international peacekeepers. Postal authorities in Delhi issued overprinted sets for use by troops in Korea in 1953; Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam in the 1950s and 1960s; and Gaza in 1965.)

rent definitive series, overprinted “U.N. Force (India) Congo.” This set sells for a modest sum, mint or used, though cancelled copies on postally used covers mailed in the Congo might command a higher price. (Indians must have been proud of their role as international peacekeepers. Postal authorities in Delhi issued overprinted sets for use by troops in Korea in 1953; Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam in the 1950s and 1960s; and Gaza in 1965.)

rring, to me at least, to study the first set of Katanga stamps — originally issued to celebrate the independence of the Republic of the Congo, showing a map of the whole country — with the name “Congo” obliterated by the bold overprint, “L’Etat du Katanga.” A smaller overprint cleverly covers the inscribed date of Congolese independence, “30 Juin,” with a new “11 Juillet,” Katangan Independence Day — while keeping the “1960” date uncovered. In this way, the secessionist government celebrated its own independence by repurposing stamps whose central image depicted the nation from which Katanga seceded. It is as if the U.S. Confederacy in 1861 put out a set of overprinted stamps with a map including its giant enemy to the north.

rring, to me at least, to study the first set of Katanga stamps — originally issued to celebrate the independence of the Republic of the Congo, showing a map of the whole country — with the name “Congo” obliterated by the bold overprint, “L’Etat du Katanga.” A smaller overprint cleverly covers the inscribed date of Congolese independence, “30 Juin,” with a new “11 Juillet,” Katangan Independence Day — while keeping the “1960” date uncovered. In this way, the secessionist government celebrated its own independence by repurposing stamps whose central image depicted the nation from which Katanga seceded. It is as if the U.S. Confederacy in 1861 put out a set of overprinted stamps with a map including its giant enemy to the north.

r breakaway republic was the central state of South Kasai, declared by Luba leader Albert Kalonji in August, 1960. It was a half-hearted effort — there was never a complete break wi

r breakaway republic was the central state of South Kasai, declared by Luba leader Albert Kalonji in August, 1960. It was a half-hearted effort — there was never a complete break wi th the federal government. This unlikely nation started out like its more

th the federal government. This unlikely nation started out like its more ai.” I have one (shown here), and I hope it has some value. The stamps were not recognized by the Universal Postal Union, and while you can find them occasionally on eBay, they are not listed in most catalogues. Prices for South Kasai stamps are not high, but I believe there is some value to them because of their unusual historical provenance, their sheer oddity, and limited numbers.

ai.” I have one (shown here), and I hope it has some value. The stamps were not recognized by the Universal Postal Union, and while you can find them occasionally on eBay, they are not listed in most catalogues. Prices for South Kasai stamps are not high, but I believe there is some value to them because of their unusual historical provenance, their sheer oddity, and limited numbers. he sessionist “republics” were the “Republique Populaire.” declared in Stanleyville to the northwest in 1964, and the “Congo” rebellion in the northern area of Katanga, centered on

he sessionist “republics” were the “Republique Populaire.” declared in Stanleyville to the northwest in 1964, and the “Congo” rebellion in the northern area of Katanga, centered on

Postal authorities in Albertville used leftover supplies of stamps from Katanga, overprinting them simply, “Congo.” The result, in effect, was a set of stamps designed and printed by Katanga, a defunct state that had seceded from the Congo, now appropriated by a subsidiary secessionist state around Albertville and relabeled “Congo.” Is this a step forward, backward or sidewise? To com

Postal authorities in Albertville used leftover supplies of stamps from Katanga, overprinting them simply, “Congo.” The result, in effect, was a set of stamps designed and printed by Katanga, a defunct state that had seceded from the Congo, now appropriated by a subsidiary secessionist state around Albertville and relabeled “Congo.” Is this a step forward, backward or sidewise? To com pound the muddle, the rebels in Albertville managed to take the 10-centimes stamp from the 1953 Flower series, and stamp their “Congo” claim directly on top of the “Katanga” overprint that was meant to supplant the crossed-out “Belgish Congo Belge” inscription. The result is a palimpsest (a word I have been waiting for years to use, which means a series of superimposed images). The stamp pictured here is listed on eBay (price: $450). The more you look at it, the more indecipherable it becomes — an apt emblem for the state of affairs at Albertville in June of 1964, and perhaps for the Congo as a whole …

pound the muddle, the rebels in Albertville managed to take the 10-centimes stamp from the 1953 Flower series, and stamp their “Congo” claim directly on top of the “Katanga” overprint that was meant to supplant the crossed-out “Belgish Congo Belge” inscription. The result is a palimpsest (a word I have been waiting for years to use, which means a series of superimposed images). The stamp pictured here is listed on eBay (price: $450). The more you look at it, the more indecipherable it becomes — an apt emblem for the state of affairs at Albertville in June of 1964, and perhaps for the Congo as a whole … reliable Scott Standard Postage Stamp Catalogue. Here is what it said: “Miniature sheets … were printed in 1944 by the Belgian government in London and given to the Belgian political review, Message, which distributed them to its subscribers, one a month.” Scott valued each sheetlet at $12.50. The Scott catalog continued: “Remainders of these eight miniature sheets received marginal overprints in various colors in 1950, specifying a surtax of $100f per sheet and paying tribute to the Universal Postal Union. These sheets, together with the four of Ruanda-Urundi, were sold for the Committee of Cultural Works (and not at post offices) in sets of 12 for 1,217.15 francs.” Scott valued the series at “about $150. On eBay today, the series with white margins sells for $799, the series with the decorative borders is priced at $1,799.

reliable Scott Standard Postage Stamp Catalogue. Here is what it said: “Miniature sheets … were printed in 1944 by the Belgian government in London and given to the Belgian political review, Message, which distributed them to its subscribers, one a month.” Scott valued each sheetlet at $12.50. The Scott catalog continued: “Remainders of these eight miniature sheets received marginal overprints in various colors in 1950, specifying a surtax of $100f per sheet and paying tribute to the Universal Postal Union. These sheets, together with the four of Ruanda-Urundi, were sold for the Committee of Cultural Works (and not at post offices) in sets of 12 for 1,217.15 francs.” Scott valued the series at “about $150. On eBay today, the series with white margins sells for $799, the series with the decorative borders is priced at $1,799. ou about these stamp sheets? How about as an emblem imperial disassociation? An example of the oblique colonial view, disengaged, distanced, perhaps even a bit sentimental (Congo!). These sheets bespeak a European population of the 1940s, profoundly, even willfully ignorant of prevailing conditions in the Congo and the discriminatory customs and legal processes; directly or indirectly, they were complicit in those racist laws, practices and opinions. The stamps were designed and printed in London. Many Belgian Congo stamps were produced by Waterlow and Sons Ltd. In 1944, with the Belgian government-in-exile now located in the British capital, you might consider this a philatelic favor done by one imperial power for another — with a tidy profit, to be sure. Given the grim distractions of wartime, these charming little sheetlets must have been welcome surprises. They were distributed, gratis, to subscribers of Message, one accompanying each monthly issue. Look closely below, and you will see special side perforations in the sheetlets that allowed them to be stapled into the larger publication, to be safely removed later by collectors. The more elaborate, bordered sheets were sold with a 10-fold markup to honor the Universal Postal Union and benefit the Committee of Cultural Works.

ou about these stamp sheets? How about as an emblem imperial disassociation? An example of the oblique colonial view, disengaged, distanced, perhaps even a bit sentimental (Congo!). These sheets bespeak a European population of the 1940s, profoundly, even willfully ignorant of prevailing conditions in the Congo and the discriminatory customs and legal processes; directly or indirectly, they were complicit in those racist laws, practices and opinions. The stamps were designed and printed in London. Many Belgian Congo stamps were produced by Waterlow and Sons Ltd. In 1944, with the Belgian government-in-exile now located in the British capital, you might consider this a philatelic favor done by one imperial power for another — with a tidy profit, to be sure. Given the grim distractions of wartime, these charming little sheetlets must have been welcome surprises. They were distributed, gratis, to subscribers of Message, one accompanying each monthly issue. Look closely below, and you will see special side perforations in the sheetlets that allowed them to be stapled into the larger publication, to be safely removed later by collectors. The more elaborate, bordered sheets were sold with a 10-fold markup to honor the Universal Postal Union and benefit the Committee of Cultural Works. d societies. Yet the words have a painful poignancy, for they represent what the Congo could have become, should have become, but has fallen tragically short of becoming.

d societies. Yet the words have a painful poignancy, for they represent what the Congo could have become, should have become, but has fallen tragically short of becoming. s issued in October, 1962. The set originally came out in January, honoring Dag Hammerskjold, the United Nations envoy who was killed in 1961 when his plane crashed on a peace mission to the Congo. Hammerskjold had made at least four other trips to the region. In September 1961, his plane went down near Ndola, Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), close to the Congo border. Hammerskjold and 14 others were killed. One theory is that the plane was shot down on the orders of Union Miniere, the mining giant that was resisting U.N. intervention. Former president Harry Truman added to the furor when he was quoted as saying that Hammarskjold “was on the point of getting something done when they killed him.” Truman added: “Notice that I said ‘when they killed him’.”

s issued in October, 1962. The set originally came out in January, honoring Dag Hammerskjold, the United Nations envoy who was killed in 1961 when his plane crashed on a peace mission to the Congo. Hammerskjold had made at least four other trips to the region. In September 1961, his plane went down near Ndola, Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), close to the Congo border. Hammerskjold and 14 others were killed. One theory is that the plane was shot down on the orders of Union Miniere, the mining giant that was resisting U.N. intervention. Former president Harry Truman added to the furor when he was quoted as saying that Hammarskjold “was on the point of getting something done when they killed him.” Truman added: “Notice that I said ‘when they killed him’.”

hostess at lively diplomatic parties held at our house. Visiting celebrities included Marian Anderson, Jack Teagarden. John Glenn, the Dorian Quintet and Buckminster Fuller. Mother was gracious, Pa was gallant, liquor flowed. Mother would charm the men and bond with the ladies, using smarts and poise acquired at Coe

hostess at lively diplomatic parties held at our house. Visiting celebrities included Marian Anderson, Jack Teagarden. John Glenn, the Dorian Quintet and Buckminster Fuller. Mother was gracious, Pa was gallant, liquor flowed. Mother would charm the men and bond with the ladies, using smarts and poise acquired at Coe

ental stone facades, towers and ruins — the latter untouched since the ravages of the Franco-Palatine wars and lightning strikes hundreds of years earlier. My twin sister Anne and I, just turned 14, were completely bilingual by this time. (Indeed, I recently had ranked second in my class — in German!) I must have been indistinguishable from the locals with my blond hair, accentless German and shiny black Lederhosen. Every morning we would head off by bicycle or Strassenbahn to the Englische Institut, a German-language school where we had advanced through the classes, from Quinta or Quarta, Unterterzia and Oberterzia to Untersekunda, the rough equivalent of eighth grade. After school we would make the return trip, mount the hill past Heidelberg University and climb the 76 steps to home. When we first arrived, I was disappointed not to be attending the American school attached to the massive U.S. military installations in Heidelberg, and missing out on life in the suburban precincts of Mark Twin Village and, a little further out of town, Patrick Henry Village. By this time, however, I was pretty well assimilated. I enjoyed friendships with German and American kids, played Little League baseball, went to the PX for American movies. I was pretty comfortable in two worlds.

ental stone facades, towers and ruins — the latter untouched since the ravages of the Franco-Palatine wars and lightning strikes hundreds of years earlier. My twin sister Anne and I, just turned 14, were completely bilingual by this time. (Indeed, I recently had ranked second in my class — in German!) I must have been indistinguishable from the locals with my blond hair, accentless German and shiny black Lederhosen. Every morning we would head off by bicycle or Strassenbahn to the Englische Institut, a German-language school where we had advanced through the classes, from Quinta or Quarta, Unterterzia and Oberterzia to Untersekunda, the rough equivalent of eighth grade. After school we would make the return trip, mount the hill past Heidelberg University and climb the 76 steps to home. When we first arrived, I was disappointed not to be attending the American school attached to the massive U.S. military installations in Heidelberg, and missing out on life in the suburban precincts of Mark Twin Village and, a little further out of town, Patrick Henry Village. By this time, however, I was pretty well assimilated. I enjoyed friendships with German and American kids, played Little League baseball, went to the PX for American movies. I was pretty comfortable in two worlds.

collector-friend Jurgen lived in Leimen, a nearby village. He picked up my practice of improvising these first days covers, and kept sending me samples for more than a year after I left town. Now that’s philatelic friendship!)

collector-friend Jurgen lived in Leimen, a nearby village. He picked up my practice of improvising these first days covers, and kept sending me samples for more than a year after I left town. Now that’s philatelic friendship!) ction of stamps, purchased at face value, which obliging postal authorities would send back to me, sometimes in envelopes embellished with a variety of current issues. Some of these stamps have increased nicely in value. (One example: the 1953 Queen Elizabeth II definitive set from Ascension, which cost me less than $5, now has a catalog value of $150+.)

ction of stamps, purchased at face value, which obliging postal authorities would send back to me, sometimes in envelopes embellished with a variety of current issues. Some of these stamps have increased nicely in value. (One example: the 1953 Queen Elizabeth II definitive set from Ascension, which cost me less than $5, now has a catalog value of $150+.)

the Belgian Congo in the middle years — 1920s to 1950s. The “mask” set of 1948 was striking, and quite common, so a few of them may have found their way into my collection. I certainly didn’t consider the Congo a specialty, like British Colonies. As it turned out, early Congo stamps were quite advanced. The 1894 multicolor definitives from the Congo Free State were exquisite engravings of local scenes, printed in black within exotic ornamental borders in different colors. Some stamps in this early set are quite affordable, and subsequent sets that used the same designs are cheap and easily available, both cancelled and mint. (It’s remarkable to think there was so much letter traffic from the Congo so long ago …) Other early Congo stamps, and others later on, are valuable. Little did I know that when I traveled to the Congo in the fall of 1962, I would be launching a philatelic expedition that now, a half-century later, has produced a nearly complete collection of stamps from the Congo. That means starting with Belgian King Leopold’s Congo Free state in 1889, then the Belgian Congo beginning in 1908, continuing past Independence Day June 30, 1960. (Indeed, as I write this, I am awaiting impatiently delivery of a key stamp filling one of my few gaps — the 50f stamp of the flower series of 1953, which I found at the Stamps to Go online store for $7.50) I am certain this collection is very valuable — worth thousands, I expect. The first set alone

the Belgian Congo in the middle years — 1920s to 1950s. The “mask” set of 1948 was striking, and quite common, so a few of them may have found their way into my collection. I certainly didn’t consider the Congo a specialty, like British Colonies. As it turned out, early Congo stamps were quite advanced. The 1894 multicolor definitives from the Congo Free State were exquisite engravings of local scenes, printed in black within exotic ornamental borders in different colors. Some stamps in this early set are quite affordable, and subsequent sets that used the same designs are cheap and easily available, both cancelled and mint. (It’s remarkable to think there was so much letter traffic from the Congo so long ago …) Other early Congo stamps, and others later on, are valuable. Little did I know that when I traveled to the Congo in the fall of 1962, I would be launching a philatelic expedition that now, a half-century later, has produced a nearly complete collection of stamps from the Congo. That means starting with Belgian King Leopold’s Congo Free state in 1889, then the Belgian Congo beginning in 1908, continuing past Independence Day June 30, 1960. (Indeed, as I write this, I am awaiting impatiently delivery of a key stamp filling one of my few gaps — the 50f stamp of the flower series of 1953, which I found at the Stamps to Go online store for $7.50) I am certain this collection is very valuable — worth thousands, I expect. The first set alone  (pictured here) is worth hundreds. (I have it complete.) I am missing a few stamps here and there — like the first parcel post stamp in 1887 (catalog value: $400+; note empty space on page). However, less than a handful are missing of the more than 400 stamps issued by the colonial administration. This collection is indeed superb, and I can’t wait to tell you more about it. First, however, a word or more of historical context.

(pictured here) is worth hundreds. (I have it complete.) I am missing a few stamps here and there — like the first parcel post stamp in 1887 (catalog value: $400+; note empty space on page). However, less than a handful are missing of the more than 400 stamps issued by the colonial administration. This collection is indeed superb, and I can’t wait to tell you more about it. First, however, a word or more of historical context. lic challenge. Since Belgium itself was bilingual — French and Flemish — the same duality would have to be reflected somehow on the stamps of its new overseas territory. French was the only language used on stamps from Leopold’s suzerainty. Now all stamps from the colony had to accommodate both languages of its new colonial masters. This awkward design requirement has been shared by other bilingual stamp-issuing nati

lic challenge. Since Belgium itself was bilingual — French and Flemish — the same duality would have to be reflected somehow on the stamps of its new overseas territory. French was the only language used on stamps from Leopold’s suzerainty. Now all stamps from the colony had to accommodate both languages of its new colonial masters. This awkward design requirement has been shared by other bilingual stamp-issuing nati Flamands! A year later, in 1909, the colony got the first set of its own — a four-stamp group that incorporated the earlier designs with the French only inscriptions. Flemish Brussels must have been in a tizzy. (Gott in Himmel! Will these pesky Walloons never show us proper respect? Congo is every bit as much ours as theirs!) Finally, in 1910, the first bilingual stamps began trickling out. The clever designers used the same engraved scenes from the 1890s — of the port city of Matadi, the Congo river at Stanley Falls, a river

Flamands! A year later, in 1909, the colony got the first set of its own — a four-stamp group that incorporated the earlier designs with the French only inscriptions. Flemish Brussels must have been in a tizzy. (Gott in Himmel! Will these pesky Walloons never show us proper respect? Congo is every bit as much ours as theirs!) Finally, in 1910, the first bilingual stamps began trickling out. The clever designers used the same engraved scenes from the 1890s — of the port city of Matadi, the Congo river at Stanley Falls, a river  steamer, hunting elephants and others. Most remarkable is a rendering of a smoke-belching engine towing cars across the M’pozo River on an elevated bridge. Remember, this design dates to the 1890s. Building the Matadi-Leopoldville railroad through the Congo was a mammoth undertaking that displayed Leopold’s relentlessness. While his stamp designers celebrated this engineering triumph, little was said about the terrible toll of this arduous railway construction project. It took three years to advance the first 14 miles, and many more years to reach Stanley Pool. Some 132 Belgian professionals and other Europeans fell victim to accidents and pestilence. But most of the victims — at least 1,800 in the first two years alone — were the poor Congolese, toiling and dying as vassals to their “roi souverain.” The new stamps bore alternating titles, “Congo Belge” first, “Belgisch Congo” second, and bilingual references to “centimes” or “centiemen,” “francs” or “franken.” (This set remained in circulation for many years, in many permutations, as we shall see.)

steamer, hunting elephants and others. Most remarkable is a rendering of a smoke-belching engine towing cars across the M’pozo River on an elevated bridge. Remember, this design dates to the 1890s. Building the Matadi-Leopoldville railroad through the Congo was a mammoth undertaking that displayed Leopold’s relentlessness. While his stamp designers celebrated this engineering triumph, little was said about the terrible toll of this arduous railway construction project. It took three years to advance the first 14 miles, and many more years to reach Stanley Pool. Some 132 Belgian professionals and other Europeans fell victim to accidents and pestilence. But most of the victims — at least 1,800 in the first two years alone — were the poor Congolese, toiling and dying as vassals to their “roi souverain.” The new stamps bore alternating titles, “Congo Belge” first, “Belgisch Congo” second, and bilingual references to “centimes” or “centiemen,” “francs” or “franken.” (This set remained in circulation for many years, in many permutations, as we shall see.) bilingually speaking. The colony issued two identical sets of definitive stamps: one set listed “Congo Belge,” abov

bilingually speaking. The colony issued two identical sets of definitive stamps: one set listed “Congo Belge,” abov e “Belgisch Congo,” the other reversed the order. (Both sets are valued the same in catalogs; philately did not take sides in this bilingual balancing act.) In the 1950s, a two-set issue of four stamps did the same thing: one set was inscribed French

e “Belgisch Congo,” the other reversed the order. (Both sets are valued the same in catalogs; philately did not take sides in this bilingual balancing act.) In the 1950s, a two-set issue of four stamps did the same thing: one set was inscribed French  first, the other Flemish first. Take your pick. In this case, no two stamps in either set are valued the same, but I can’t discern any favoritism of one language over another. And that is about as far into the philatelic weeds as we need to go on that subject, wouldn’t you agree?

first, the other Flemish first. Take your pick. In this case, no two stamps in either set are valued the same, but I can’t discern any favoritism of one language over another. And that is about as far into the philatelic weeds as we need to go on that subject, wouldn’t you agree? as they age. First is Victoria, who appeared as completely different personae during her long reign: as a swanlike beauty in the early Chalon portraiture; a classically sculpted empress-in-profile in her middle decades; finally, as the stout dowager queen, under an elaborate headdress, gazing wistfully into the light …

as they age. First is Victoria, who appeared as completely different personae during her long reign: as a swanlike beauty in the early Chalon portraiture; a classically sculpted empress-in-profile in her middle decades; finally, as the stout dowager queen, under an elaborate headdress, gazing wistfully into the light … in 1850 of a simply dressed monarch sitting demurely on her throne. (SInce I don’t make a specialty of collecting Australia, I cannot offer a worthy sampling here. But you can find wonderful, full-color renderings of all the Victoria stamps you’d want to see — or buy — on eBay and other sites.)

in 1850 of a simply dressed monarch sitting demurely on her throne. (SInce I don’t make a specialty of collecting Australia, I cannot offer a worthy sampling here. But you can find wonderful, full-color renderings of all the Victoria stamps you’d want to see — or buy — on eBay and other sites.)